The sound of a guitar blends with the light rail siren near the Central Bus Station plaza on Jaffa Street in Jerusalem. Even in the chill of a Jerusalem winter, the space between the bus station and the Yitzhak Navon train station fills with boys and girls seeking refuge on the city’s main street.

They wander along the tracks of the Red Line light rail, from the Central Bus Station through Mahane Yehuda market to Zion Square. Alongside the guitar music are plastic cups filled with alcohol. Drugs circulate freely.

“Every type of drug is available here,” said Danny Brooks, director of Jerusalem's youth advancement division. “Today it’s so simple for them to get whatever they want. More than a decade ago, he said, the minimum age of youths hanging around the Central Bus Station area was 16. “Today you see children here as young as 8 or 9.”

Data recently presented to the municipal committee for eradicating violence and promoting youth paints a troubling picture: On Thursday evenings and nights, about 5,000 at-risk youths gather in Mahane Yehuda market and the surrounding city center.

On average, two violent fights break out each week, sometimes involving stabbings. Dozens of calls are made to Magen David Adom and police, and at least two new criminal cases are opened weekly.

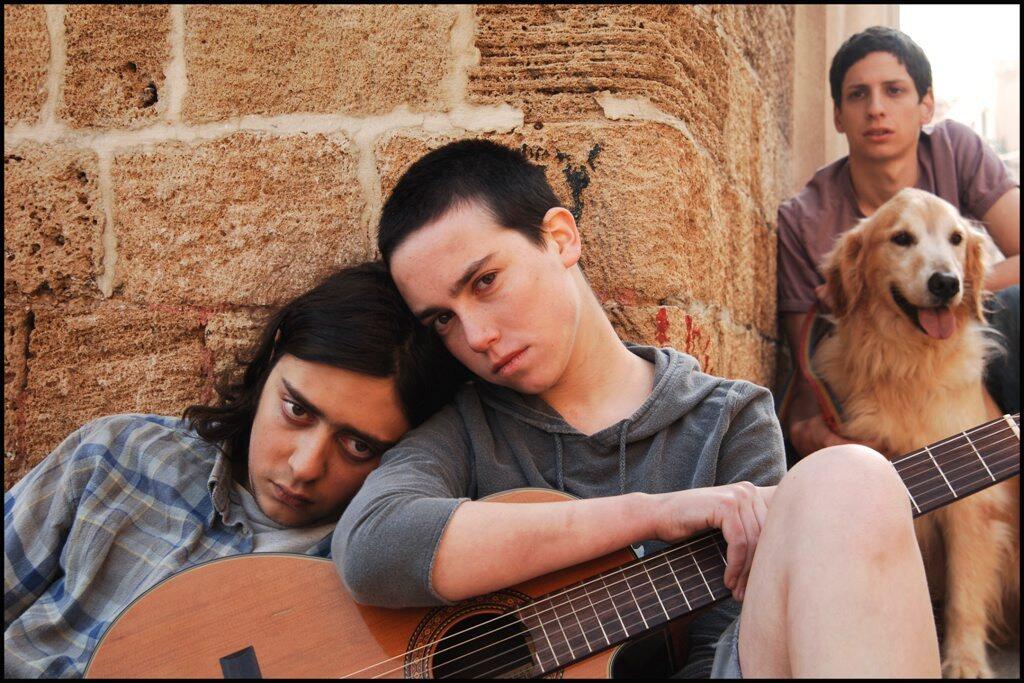

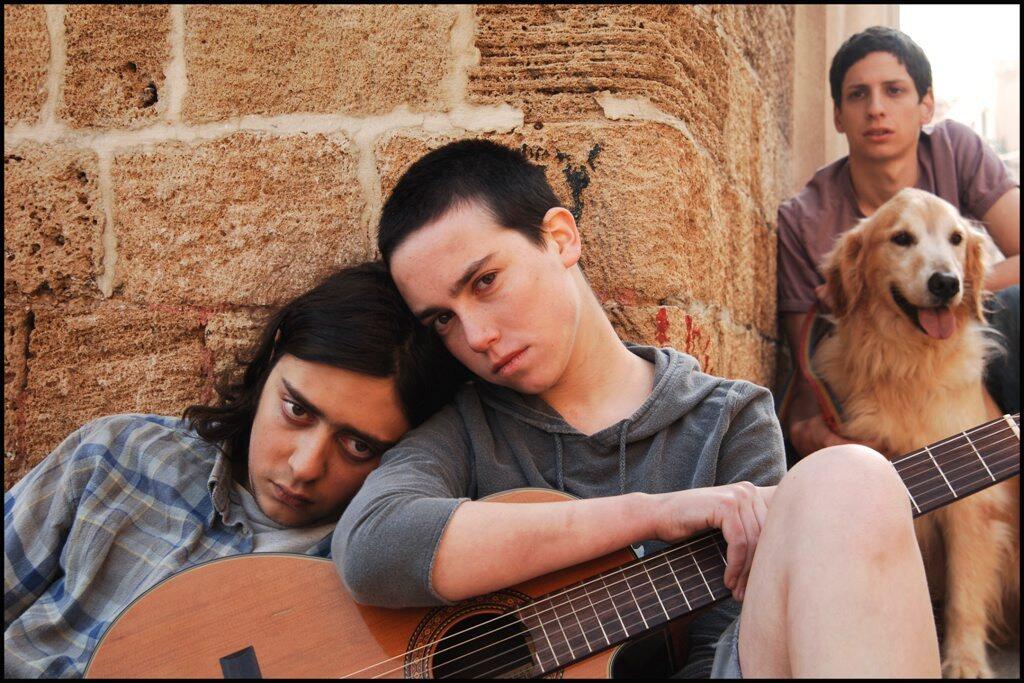

7 View gallery

Scene from the film "Someone to Run With," based on a novel by David Grossman

(Photo: Eldad Rafaeli)

Jerusalem’s streets have long been a haven for dropouts. In 2000, author David Grossman published “Someone to Run With,” which exposed the lives of teens on the city’s streets. Until a few years ago, most of the youths came from secular or national religious homes. Today, boys and girls from ultra-Orthodox families are also part of the scene.

13-year-old drug courier

Brooks recounted the case of a 13-year-old girl who grew up in a closed Hasidic sect in the city and ended up on the streets. Over time, she began working as a courier for a drug dealer. One day, she told her social worker she had asked her boss to inject her with heroin because she wanted to experience the drugs she was passing from hand to hand.

“Unfortunately, this isn’t necessarily an extreme story,” Brooks said. “Sometimes you go home agonized with terrible stomach pains from what you see on the street.”

7 View gallery

Danny Brooks. "Agonized with pain from what you see on the street"

(Photo: Gil Yohanan)

Deputy Mayor Adir Adir Schwarz, who holds the youth portfolio, opened the committee discussion with a personal story. He described how his high school friend died after being sold a toxic substance marketed as a drug in the city center

“The phenomena that existed then still exist today, in slightly different ways but in much larger numbers. This is a real matter of life and death,” Schwarz said. "It often appears that enforcement at Mahane Yehuda market focuses on minor issues rather than the main problems, such as businesses that sell alcohol to minors. A business that does that should be shut down immediately. We will continue to act without rest. Otherwise, the next disaster is already around the corner.”

Along Jaffa Street, 27 outreach points operated by municipal social services and nonprofits offer assistance to at-risk youths. They provide shelter, conversation and a cup of hot tea. Sometimes it is a small room, sometimes a covered area, and sometimes just a mat on the sidewalk.

“There are kids here in deep distress who push away everything possible, but we believe that at the end of the day they want to connect,” Brooks said. “The big challenge for staff is how to get through to them. The goal is to reach them and build trust. To be with them.”

In recent years, Mahane Yehuda has become Jerusalem’s main nightlife hub, packed with restaurants and bars. Along with that growth, more dropouts have arrived. “They come here to do everything they can’t do at home,” Brooks said. “It could be a seemingly normative teen, a teen from East Jerusalem or an ultra-Orthodox boy. The street is fertile ground for at-risk youth. Everything is available. No one is watching. You can use drugs, you can pay for sex, you can get into fights.”

A transient family

At Zion Square late one evening, Eli Kalter, 26, described how he managed to leave the streets behind. Asked where he grew up, he replied, “Everywhere or nowhere.” Kalter spoke of violence at home by his biological father, moving between houses and different ultra-Orthodox yeshivas before ending up on the streets.

“On Purim, when I was 17, I knew I wasn’t going back to yeshiva,” he said. “I found myself lost. I had no education, nothing. I only knew the ultra-Orthodox world. I was stuck in a loop of doing nothing. At night I’d go out to meet friends. We’d hang around the city bored, feeling cool because we were near the bars, smoking weed and drinking.”

What makes the street so appealing?

“There are kids who are a bit lost and find a home in each other,” Kalter said. “Someone American, a girl from Samaria who suddenly becomes a close friend, even though tomorrow she might not be here. The street feels like a temporary family.”

His turning point came when he woke up in a hospital after alcohol poisoning. He had drunk a bottle and a half of vodka he found in a Chabad synagogue. “I was excited that you could drink for free,” he recalled. “I grabbed a cup and just kept going. Looking back, I understand I was trying to suppress very difficult emotional things that happened at home and the violence there. It was a real slap in the face. I realized I had to get myself together.”

7 View gallery

“The goal is to reach the kids and build trust.” Teens at Zion Square

(Photo: Gil Yohanan)

He credits outreach workers with helping him rebuild his life. “The youth advancement staff were there, sitting with tea and backgammon. We were with hookahs, and they were always there. Available. You could talk to them,” he said. “Their presence is often invisible, because they’re not the cool ones. But if something happens to a girl here, she knows there’s a social worker nearby. That presence matters. There are social workers I still remember. The good people along the way are what make the difference.”

The street has its own rules

Kalter moved to northern Israel to attend a technological institute for ultra-Orthodox students headed by Rabbi Avraham Borodiansky. After completing his studies there, he enlisted in the Israeli Air Force’s Ofek unit. Following his military service, he did everything he could to gain university admission to study computer science and mathematics. Today, as a student, he has returned to live with his mother and sisters and also takes on parental responsibilities at home.

“From a young age I remember the sentence, ‘When someone makes a hole in the boat, it doesn’t help to explain why it’s not your fault,’” he said. “Sometimes you can choose to drown with good excuses, or to live after solving a problem you weren’t supposed to have to solve", he said, seeking to send a message to the boys and girls wandering the streets.

“I live with the awareness that no matter where I started, I’m climbing and building my way up. Where I’ll be in 10 years will be determined by the decisions I make along the way.”

7 View gallery

“There's no reality where teens won't be on the street.” Youths on Jaffa Street

(Photo: Gil Yohanan)

Not all stories end in recovery. Brooks refers to a young man he has encountered on the street for 11 years. “He’s in the same place, with the same story, and it’s sad. No matter how much we work and try to connect with him. We haven’t managed to crack it, and he hasn’t managed to find the strength to get up.

“The street has its own rules. There’s no reality in which this phenomenon disappears where there will be no youths on the street,” Brooks said. “My goal is to provide as much help as possible to those who are here. I want them at home, but reality doesn’t work that way. That’s why we’re here, to give them a response.”

Alongside the municipality, numerous nonprofits also assist at-risk youth. One of Brooks’ goals is to create coordination between all the bodies involved. “Cooperation is critical,” he said. “The directors of all the organizations meet every three months to understand different trends taking place in the city.

“We’re trying to reach a point where each organization knows its role and, instead of competing, works in partnership. In the end, all this activity comes down to the staff who go out into the field on cold nights to help.”