In a feature published in The Atlantic, journalist Shane Harris recounts how, in 2016, he found himself drawn into an extraordinary relationship with a man who claimed to be a high-ranking Iranian intelligence officer.

The story begins years earlier, in December 2011, when Iran captured a U.S. RQ-170 Sentinel stealth drone and paraded it on state television as evidence of its growing cyber and intelligence capabilities. American officials were stunned, unsure whether the drone had malfunctioned or whether Iran had learned to hijack one of the most advanced aircraft in the U.S. arsenal.

The mystery resurfaced years later when Harris received a message from someone calling himself “P,” who claimed to be part of an Iranian hacker collective called Parastoo. He said he could explain exactly how Iran brought the drone down. Skeptical but curious, Harris agreed to speak. What followed was not the rambling of an online pretender. P wanted encrypted conversations. He asked probing questions to verify Harris’s identity. And then he claimed he was not just a hacker but an officer in Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security.

Soon, he shared his real name: Mohammad Hossein Tajik.

Mohammad’s reported explanation of the drone’s capture sounded technically plausible. He said his team had intercepted its communications with assistance from Chinese advisers and forced it to land. But he admitted the drone was only a hook. Mohammad wanted something bigger.

He told Harris that he planned to reveal sensitive details about Iran’s intelligence operations as revenge against a regime he now despised. He asked Harris to publish his disclosures. Even more remarkably, he asked Harris to help him reestablish contact with the CIA, claiming he had once been an American asset. Harris refused to act as an intermediary for intelligence operations but continued to interview him as a source.

Over two months of encrypted chats, Harris found Mohammad disarming, sometimes erratic, and unexpectedly vulnerable. He joked, referenced American films, complained about loneliness, and touted his technical brilliance. He boasted of cyberattacks across the Middle East, including the 2012 Saudi Aramco breach, and described cooperation with Russia’s GRU and Hezbollah’s cyber units. Some claims were unverifiable, others astonishing, but much of what he said aligned with known Iranian capabilities.

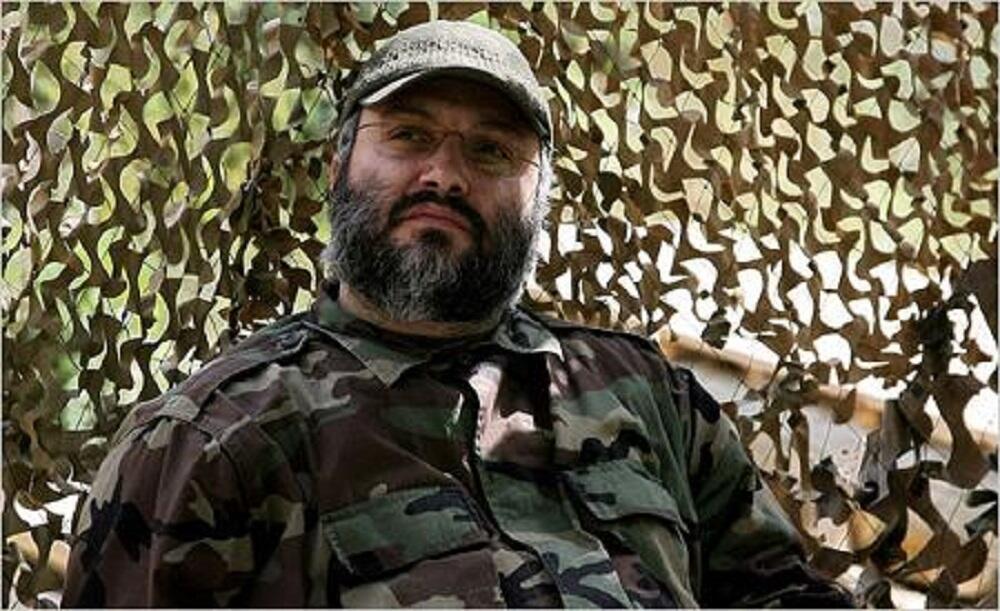

As he advanced through the intelligence ministry, Mohammad said he traveled repeatedly to Lebanon and developed close ties with senior Hezbollah commanders, including Imad Mughniyeh, the architect of the 1983 bombings of the U.S. embassy and Marine barracks in Beirut. His relationships with figures who had American blood on their hands would have made him exceptionally valuable to the CIA. Mohammad said he provided the agency with details about Hezbollah’s internal structure and about how the group’s units coordinated with Iran’s intelligence service.

The CIA had pursued Mughniyeh for decades and ultimately killed him in a joint operation with Israel in February 2008, the same year Mohammad said he began cooperating with the agency. Mohammad never tried to claim credit for American operations, which to me only strengthened his credibility, but the period when he said he worked with the CIA aligns with several significant U.S. intelligence breakthroughs in Iran. In September 2009, for example, Western leaders revealed the existence of Fordow, a secret underground uranium-enrichment facility that the Trump administration would bomb in 2025. Given his senior position, Mohammad could easily have known about the site. If he had wanted to “hurt the regime,” as he often said, he was well placed to do so.

As their conversations deepened, Harris sensed the portrait of a man living inside multiple identities. Mohammad nursed a profound hatred for the Iranian regime, which he saw as corrupt and hypocritical, yet he remained a trusted officer within it. He talked often about ego—how he was smarter than his colleagues, smarter than his CIA handlers, and uniquely positioned between adversarial intelligence systems. He hinted at a traumatic past but never said what had befallen him.

Only after his death would the truth emerge.

By July 2016, Mohammad said he was preparing to flee Iran. He planned to meet another dissident, journalist Ruhollah Zam, in Turkey and hand over documents he had secretly scanned. Harris and Mohammad scheduled another conversation for July 5. Mohammad never appeared.

Zam soon contacted Harris: Mohammad was dead.

The news raised immediate fears. Harris reviewed his security practices. Days later, the FBI contacted him, warning that Iranian actors were discussing him by name online. Now the pieces began to connect.

Zam sent Harris Mohammad’s burial certificate and messages from Mohammad’s younger brother suggesting the death was suspicious. Exiled Iranian activists circulated rumors that Mohammad’s father—a senior figure in Iran’s security establishment—had killed him to prevent further disgrace, though the full truth remains unknown.

Only then did Harris learn that Mohammad had been arrested in 2013, shortly after his CIA ties ended, when Iranian authorities discovered photos he had taken of his communications with U.S. handlers. Those photos—images he had taken “for insurance”—had instead exposed him. He was tortured in Evin Prison, subjected to boiling-water scalding, forced confinement, and psychological torment. He was charged with espionage.

Yet months later, he was unexpectedly released to await trial. Friends believed his father had intervened. Mohammad spent months recovering; his beard turned white, and he struggled to walk or sit straight. When he regained strength, he resumed leaking secrets—first to Zam and later to Harris—while quietly attempting to rebuild ties with the CIA.

To American intelligence officials, however, he had become too unstable to manage. Some believed he had been compromised by Iranian intelligence during his imprisonment. Others questioned his mental state. No CIA officer had ever met him in person, an unusual gap for such a valuable asset. By the time he reappeared in 2016, his intentions were murky at best. Was he seeking asylum, revenge, money, validation? Or had he become a double or triple agent, whether willingly or under coercion?

Mohammad himself once sent Harris a cryptic message describing his life as “a double, turning into a triple and later to a nothing, everything, ticking bomb.” At the time, the line puzzled Harris. In hindsight, it read like a warning from someone who no longer knew which side he was on.

On July 5, 2016, the day he was scheduled to speak with Harris, Mohammad was found dead in his home. His belongings, including his computer, were seized. His father stood apart from mourners at the burial. No cause of death was listed.

Years later, Harris learned that Zam—the dissident who helped uncover details of Mohammad’s end—had himself been lured to Iraq by Iranian operatives, kidnapped, and executed in 2020. Those who knew parts of Mohammad’s story were being silenced.

Today, only traces of Mohammad Tajik exist online. He never became the whistleblower he imagined. But his surviving correspondence reveals a portrait of a gifted and tormented man, trapped between rival intelligence worlds, consumed by ego and fear, and searching for a way to escape the regime he had once served.

He never found one.