On the balcony of Elkana Bohbot’s apartment, above his mother’s home in Mevaseret Zion, a breeze moves through the air, but the atmosphere feels heavy. He speaks slowly, stops, goes back, tries to stitch hours and days into one continuous picture. Sometimes he closes his eyes, sometimes he searches for words, sometimes he asks for a moment.

Two years in captivity do not arrange themselves into a linear story, but into fragments of memory. Beatings, hunger, darkness, fear, again and again. Only after placing the present on the table does he manage to draw a coherent picture of what he truly went through beneath the ground of the Gaza Strip, and what life looks like when every day is a struggle to stay alive.

“These were two years of suffering and uncertainty,” Bohbot says. “Every day that began, I had no idea whether I would live or die. I was cut off from everything, and especially from Rivka and Reem,” he says, referring to his wife and his son, who was nearly three years old when he was abducted. “All the time, thoughts. What’s happening to them? Where are they? What did they tell the child? How is he coping? It drives you crazy. That was the hardest part.”

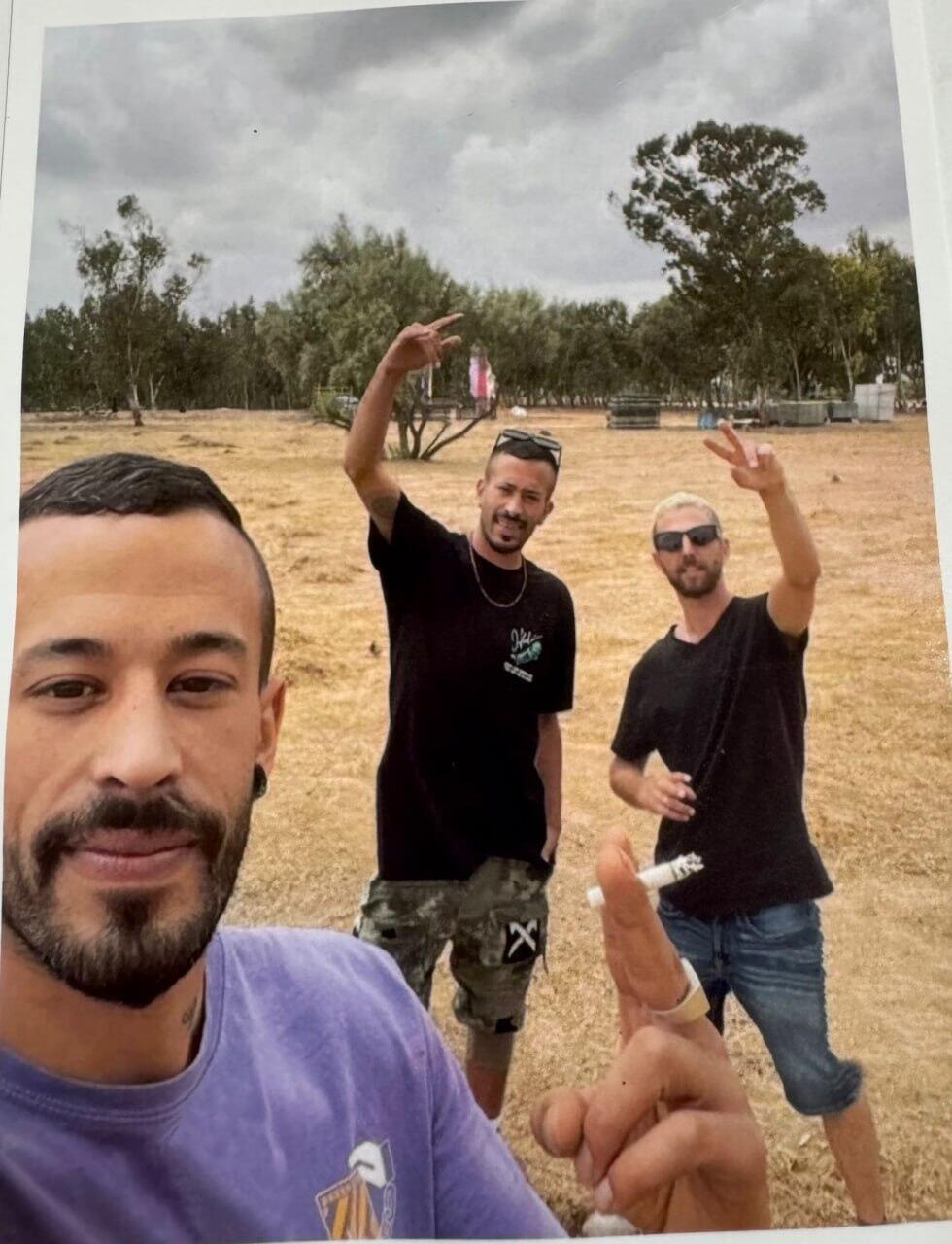

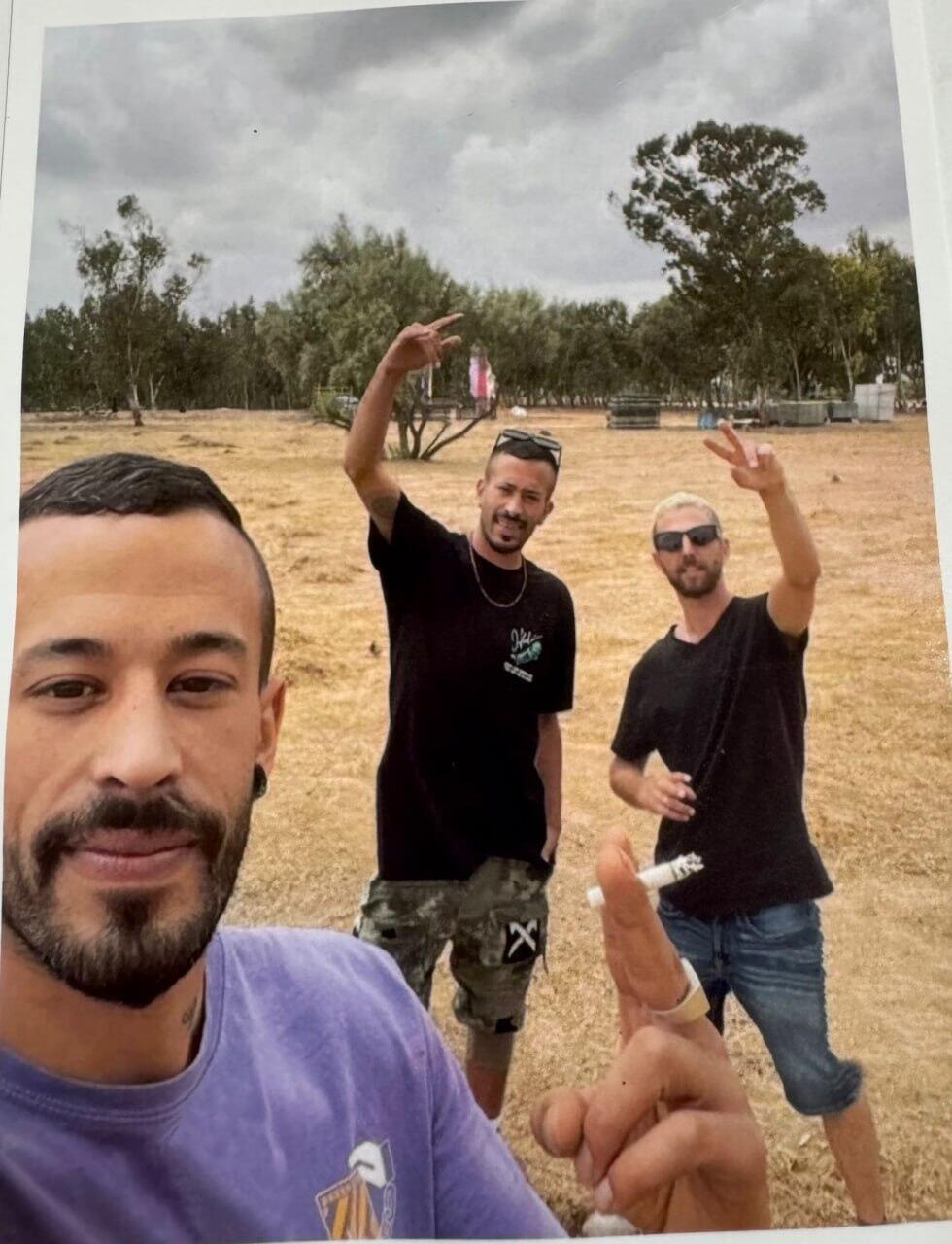

Before October 7, Bohbot was a husband and father, an entrepreneur, and a man of music and friendships. He was one of the organizers of the Nova music festival, a project that filled him with pride and one he worked on for six months with his partners and childhood friends, twin brothers Osher and Michael Vaknin. The Hamas terror attack turned the site into a killing field. His two friends were murdered, and he was abducted to Gaza, where he remained for 738 days until he was released alongside 19 other hostages in October.

“We waited so long for this production and worked endlessly on it,” he says. “After all the difficulties Rivka and I went through, it was a peak moment. We were living with our parents, there were complications, our financial situation was not good, and I finally reached a point where I went all in. It seemed to succeed. Then the nightmare came, and everything fell apart.”

As the rocket fire began, Bohbot understood he had to shut down the dance floor at Nova. His calls for partygoers to disperse were documented on video.

“People lay down on the ground in panic, and then the chaos started,” he recalls. “A manhunt. A massacre. Bodies. Things happened very fast. Suddenly, about 70 terrorists arrived. They moved through with weapons, smashed car windows, and carried out executions. They shot people who were already dead.”

Bohbot was captured alive, still not fully understanding what awaited him.

“They loaded us onto a pickup truck and drove us to Gaza,” he continues. “I happened to be lying on top of other people, so I absorbed all the blows. Every three minutes, someone would lift my head and beat me. Another would fire his weapon and then press the hot barrel against my leg, again and again. In Gaza, they thought I might have a bullet in my leg, because it was open to the bone from the burns caused by the heated weapon. They started digging into it. I refused. I told them that from my perspective, they could amputate it, just not touch it.”

Few Israelis will forget one of the first videos released from Gaza on the morning of October 7. A group of wounded Israelis lie in a dark storage room, their hands bound behind their backs, faces turned toward the floor, as the camera moves among them. Bohbot’s terrified gaze became seared into public memory.

“The first thing they did to us in Gaza was put us in that room and beat us,” Bohbot says. “My head was filled with insane thoughts. I talked to God. I told Him, ‘Release me from this suffering. Give me a bullet in the head.’ Just let me die, as long as I don’t get lynched. I thought only about Reem growing up knowing his father was murdered in a Hamas lynching.

Elkana Bohbot returns from Hamas captivity

(Video: IDF)

“During the abduction, I took such a hard punch that I felt myself starting to lose consciousness. I thought, if this really happens, what will the terrorist do with me? Will he think I’m dead and make sure to finish the job? Everything around me turned black, so I started counting to 10 over and over. Just don’t pass out.”

The captivity became a routine of horrors. Or as Bohbot defines it, “Time passes, the suffering stays.” Like many other hostages, he says the psychological abuse by the terrorists guarding him was often worse than the physical abuse.

“I know soldiers are being killed, hostages are dying, and I’m still alive,” he says. “Another hour, another day, another evening, another night, and that’s it, you can’t anymore. Many times I said I couldn’t go on. I reached states of dissociation and shutdown. I had already understood as a soldier that if I were taken captive, I would be physically abused. But mentally I was less prepared. That destroyed me.

“I’m a father who did everything with Reem. We’re best friends. The thoughts about him destroyed me. The terrorists realized that this was my weak point, even more than the physical aspect, so they abused me exactly there. They told me my mother was dead. That Rivka was no longer with me, or that she was dead too.

“One terrorist once asked me my son’s name, and when I answered, he said, ‘I pray that your son will die,’ and then he knelt and began to pray in front of me. And you can’t do anything. During the war with Iran they told me a missile had fallen and killed a woman and a child. You have no idea what’s real and what isn’t.”

Video of Elkana Bohbot from Hamas captivity in Gaza

Four videos of Bohbot were filmed in the dark tunnels of Gaza and released one after another. But there is another video, brutal in its cruelty, that was never published, and which Bohbot now describes for the first time.

“They dictated what we had to say, but the screaming was real,” he says. “With the video that never came out, they went the furthest. They drew blood from our hands. They beat us because they wanted us injured for the filming. They wanted to simulate suicide scenes.”

He shows the marks on his hands. “They actually wanted us filmed after an alleged suicide attempt, and they blew up my hand for that.”

Bohbot falls silent for a moment, his gaze dropping, then continues.

“In the last six months the situation was the hardest. They starved us, and we reached extreme states. They harassed us constantly, everywhere, even in the shower, over the smallest thing. They wanted to hurt us as much as possible, and they succeeded. It really was as bad as it could be. All this while bombs were falling near us, just meters away. You’re sure the next missile will hit you. The tunnel shakes and you’re certain you’ll be buried there. So you’re afraid. You don’t sleep.

“You’re barefoot, thrown around all day like a garbage bag, cut off from the entire world. They beat you, play with you. It’s sick. Ohad Ben Ami and I were the only ones who went to the terrorists to bring food. We went terrified, because you don’t know what will happen there. They can spit on me, and I have to say thank you.

“One of the hardest abuses was when we went to them to get food, if there was any, and then they would force us to watch videos.”

What kind of videos?

“They forced us to watch terrorists shooting soldiers or planting explosives. They also showed us videos of them beating and abusing my brothers,” he says, referring to kidnapped soldiers. “You’re so angry, and there’s nothing you can do. It’s complete helplessness. You’re in a booby-trapped tunnel, surrounded by terrorists, explosives, weapons on the walls. There’s nothing you can do.”

Other former hostages have spoken about sadistic games, including being forced to choose who among them would be executed. Bohbot says this was not a one-time incident.

“One time, a terrorist came with a box cutter,” he says. “He told us, ‘Choose who I cut a finger off.’ We screamed, begged, pleaded. It didn’t interest him. He said, ‘I need to return to my commander with a finger, with blood. Do you want him to come, or should I choose one of you?’ In the end he said, ‘Fine, next time.’”

Footage of Elkana Bohbot from the Nova Music Festival on October 7

(Video: Elkana Bohbot, Eliel Saad)

In the first week of captivity, while they were still above ground, Bohbot considered an escape attempt.

“We had an idea to overpower the terrorists while they were praying, take a white sheet, draw a Star of David, go up to the roof and signal a helicopter with a blinking flashlight,” he says. “But from that apartment they took us down into a tunnel, and from there there’s no way out.

“You have to understand that in a tunnel there’s no difference between you and a dead person. Both of you are buried underground, without air, with insects and worms. Maybe the only difference is that your heart is still beating. But other than that, you’re a corpse. No food, no air, no sounds of birds, cars, children. Thin, depressed. It’s a human experiment.”

The loss of the twins Osher and Michael Vaknin, his childhood friends and partners in producing the festival, accompanies Bohbot constantly. They did everything together, from the army to their first productions to Nova. In captivity, and even more so since his return, the guilt has not loosened its grip. Why is he alive and they are not? Why did he make it out?

5 View gallery

Twin brothers Osher and Michael Vaknin who were murdered by Hamas with Elkana (right)

Sometimes it’s a sharp, clear thought. Sometimes just a heavy weight on his chest, without words. He returns again and again to the final moments of the festival, to the small decisions, to the seconds when everything unraveled, asking himself whether anything could have been different, even when he knows there is no answer.

“It’s for life,” he says. “There’s nothing that will make me forget what happened. I wake up in the middle of the night asking, ‘Why me?’ Sometimes I completely break down. Life is stronger than everything, and you have to choose it, to move forward. But this will always be with me. Sometimes before I fall asleep, I ask Osher and Michael to come to me in a dream.”

Returning home was the most meaningful moment of your life?

“Yes, after Reem's birth. Walking out of that place on my own feet is a miracle. To come out alive after all the death I saw in those two years? I still can’t process it.”

The triggers are many. Even the sound of a camera shutter in his safe home in Mevaseret Zion sounds to him like gunfire.

“It’s like the sound of the rifle I used to hear,” he says. “It wraps around you and doesn’t let go. It shows up in everything. When I put shoes on Reem, I think about being barefoot for two years. I wash dishes and think about the utensil in the tunnel.”

Do you have a routine yet?

“No. I wake up in the morning and live hour by hour. Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night with thoughts, memories, images of death, tunnels, terrorists. And I go to sleep with them too. Sometimes I manage to enjoy and see the good, but it’s not complete. There’s always a feeling that something is missing.”

What helps?

“Seeing Rivka and Reem next to me every day. I’m also in therapy. This rehabilitation is not simple. Reconnecting with Reem after two years without a father figure is a process, and it will be long. My mother is also ill, and that’s another battle. It doesn’t make things easier. We’re fighting on many fronts.

“My dream is to give Reem a brother or sister as soon as possible, and for them to have a home here in Israel to sleep in. That’s what I want. We need that. Rivka and I, and the whole family, are in therapy and dealing with so much. We’re not managing to return to routine. And that’s all we want.”

At Bohbot’s request, the ‘L’Hoshit Yad’ association has launched a fundraising campaign on his behalf.

“I’m putting shame aside because I have no choice,” he says. “I just want to be a real husband and father to my child. I want to rehabilitate their souls and my own.”

To donate to Elkana Bohbot through the secure website, click here.