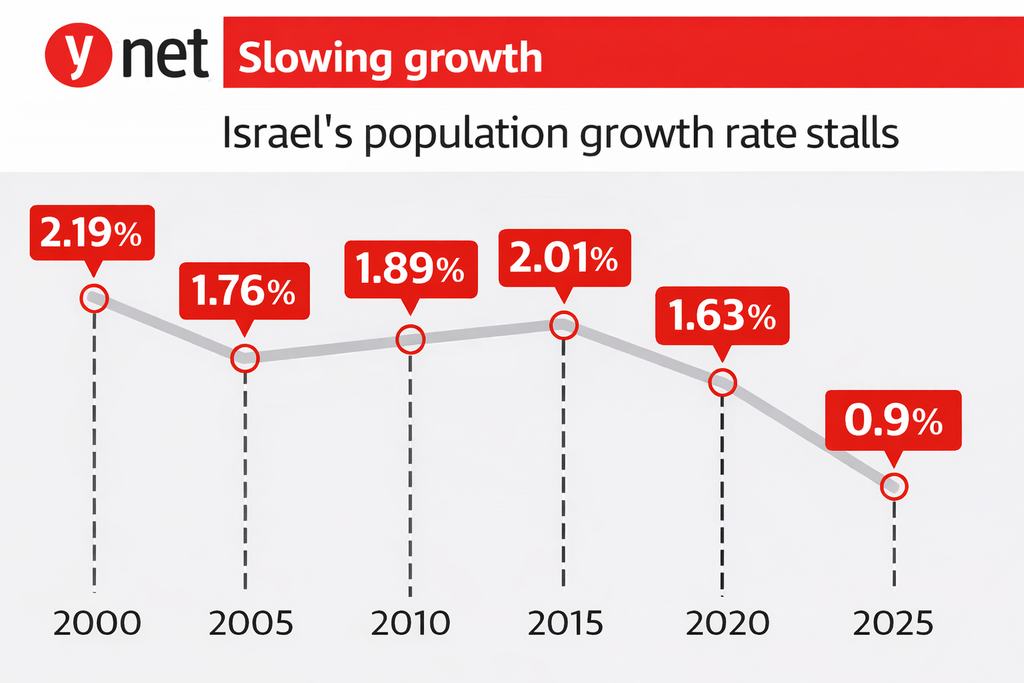

Israel’s population growth rate has stalled, reaching its lowest level since the country’s founding, according to an analysis published Wednesday by the Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel.

Since 1950, Israel’s population growth rate has stood at at least 1.5% per year, with only two brief exceptions when it dipped slightly below that level. This year, however, researchers estimate that Israel’s population grew by less than 1% for the first time, at just 0.9%.

The slowdown is the result of a rise in the number of deaths, a prolonged decline in fertility and an increase in the number of people leaving the country compared with those immigrating to Israel. While it is still too early to determine the long-term trajectory of emigration, the outlook for natural population growth appears clear.

“Israel’s peak period of natural population increase is behind us,” said Prof. Alex Weinreb, the study’s editor. “Natural growth will continue to decline.”

The projection is based on several assumptions that challenge commonly used indicators. Although the number of births over the past decade has remained strikingly stable at about 180,000 per year, an analysis of fertility trends by population group points to an overall decline in fertility rates.

Among Muslim, Druze and Christian women, the trend has been evident for years, with fertility rates in these communities falling by about 30% in recent years. Researchers now say there are early signs that fertility rates among Jewish women are also expected to decline.

According to the study’s estimates, which are based on fertility patterns by age group and an effort to project the total number of children each woman is likely to have, fertility among secular and traditional Jewish women is expected to fall within about a decade from the current range of 1.9 to 2.2 children to around 1.7. Among religious Jewish women, fertility is projected to decline from 3.74 to about 2.3 children per woman, while among ultra-Orthodox women it is expected to drop from 6.48 to 4.3.

While fertility rates in the ultra-Orthodox and religious communities remain high, the researchers note that not all children born into these communities remain there throughout their lives. Past data show that about 15% of children born into ultra-Orthodox society leave the community as adults.

Another factor contributing to the slowdown in population growth is the rising number of deaths, a trend that is expected to continue. The increase is largely driven by Israel’s age structure, as large cohorts of Jewish and Arab citizens have begun entering their 70s and 80s in recent years, ages at which mortality rates rise sharply.

For most of Israel’s history, population growth was driven primarily by natural increase, with a high number of births relative to a low number of deaths. As that balance shifts, maintaining population growth of at least 1% per year would require a positive migration balance.

Here, however, uncertainty is high. In recent years, more people have left Israel than ever before, while the number of returning residents and new immigrants has failed to keep pace. In 2025, a negative balance of about 37,000 people was recorded between those entering and those leaving the country.

Data from the first nine months of 2025 indicate that immigration to Israel this year is expected to be the lowest since 2013, excluding 2020, the year of the coronavirus pandemic. At present, most people leaving Israel were not necessarily born in the country, including a large group of immigrants who arrived in 2022 following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine.

Still, while native-born Israelis make up a smaller share of those emigrating, their absolute numbers are rising. Fewer than 20,000 Israeli-born citizens left the country in 2022, compared with more than 30,000 in 2025.

The picture, however, is more complex than it may appear. Not every departure is permanent, and temporary emigration is not necessarily negative. Two-way mobility among highly educated populations, including in academia, can serve as a means of acquiring advanced skills, fostering academic and commercial cooperation and maintaining international professional ties.

For now, however, it remains unclear whether the rise in emigration will also translate into higher numbers of Israelis eventually returning home.