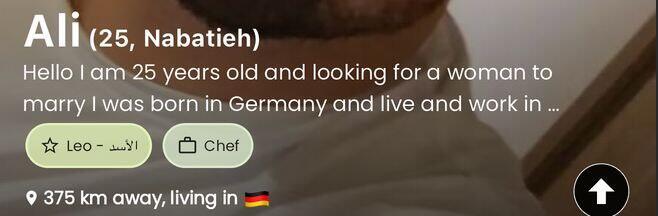

A Lebanese dating app is at the center of a growing controversy in the country, accused of deepening sectarian divisions and reviving identity-based tensions in a society still scarred by civil war.

The app, called “Taaruf,” Arabic for “getting to know,” has drawn sharp criticism in a recent article published in Al-Akhbar, a Lebanese newspaper closely affiliated with the Hezbollah terrorist group. The article warned that the app is reigniting questions of identity in Lebanon and turning algorithms into tools for sectarian and political sorting.

According to the article, the normalization of such divisions is being cultivated among the younger generation, with the virtual dating sphere threatening the concept of coexistence and “reproducing fear and stereotypes in Lebanon’s digital space.”

The author argued that during the most recent war with Israel, media coverage contributed to sharpening sectarian and religious divisions, particularly among younger Lebanese who did not experience the 1975–1990 civil war. He warned that Lebanon now faces “a new kind of civil war,” driven not by militias but by technology and economic interests exploiting a national crisis.

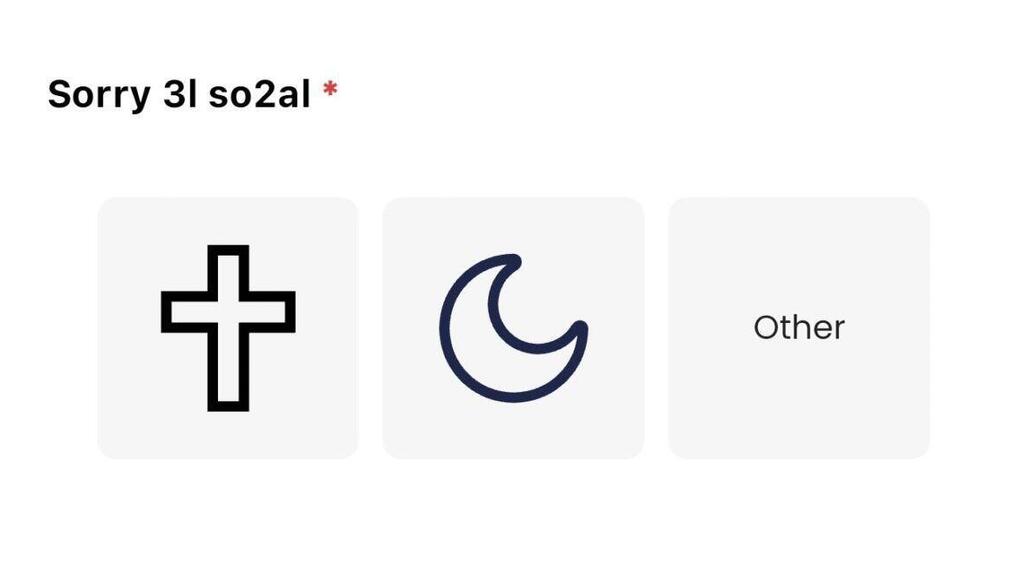

Unlike other dating apps, Taaruf asks users not only for standard details such as location and personal descriptions, but also about their religious identity. If a user selects “Muslim,” additional options appear, including foods and drinks associated with specific Islamic sects, which the article claims are meant to signal precise religious affiliation. The app also asks users to identify their political alignment, with all such information displayed on profiles, exposing young people to details the article said “should not be relevant.”

Political researcher Iyad Sakariya was quoted as calling the app dangerous. “Who said only Shiites like harissa and only Sunnis eat halawat al-jibn?” he asked, arguing that such classifications steer young people toward a new form of division.

“Chaos dominates Lebanese platforms, from moral decline to assaults on national unity,” he said.

Taaruf is a relatively new app, with its Instagram account active only since January. Promotional videos describe it as “the best way to find the right person” and promise to end users’ searches. The app emphasizes that it connects Lebanese people worldwide, not only those living in Lebanon.

The backlash comes amid Lebanon’s longstanding internal challenges over sectarian identity in a country made up of Christians, Muslims, Shiites, Sunnis, Druze and numerous other communities, diversity that has long fueled political, social and security tensions, including those involving Israel.

Hezbollah, the Iran-backed Shiite terrorist group, has been significantly weakened both militarily and politically following its war with Israel and broader regional developments over the past two years, including the fall of Syria’s Assad regime. The group has been accused by critics inside Lebanon of dragging the country into war by joining Hamas’ October 7 terror attack on Israel and bears responsibility, they say, for much of the destruction caused by the fighting.

In recent months, Hezbollah has sought to reinforce the narrative that Israel is the “common enemy” of all Lebanese and has called for internal unity, while simultaneously warning of civil war if the government in Beirut attempts to forcibly disarm the group.

Hezbollah Secretary-General Naim Qassem said earlier this month that “when we are united, they cannot do anything,” adding that alignment with Israel would “poke a hole in the ship and cause everyone to drown.”

Lebanon’s new leadership, led by President Joseph Aoun, Prime Minister Nawaf Salam and Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri, has repeatedly stressed the need to stabilize and rebuild the country, with Aoun working to distance Lebanon from foreign influence, including Iranian involvement.

Even before the current controversy, concerns had been raised in Lebanon that dating apps could enable contact with Israelis, even unintentionally. In July, Lebanon’s LBCI network reported that Israeli profiles frequently appear on dating apps used in southern Lebanon, due to distance-based algorithms that ignore national borders.

The report said that in some areas, more than half the profiles shown belonged to Israelis across the border, including Israeli soldiers, some photographed in uniform and others in civilian clothing. The article warned that personal awareness is the first line of defense against unintended contact.

Similar warnings appeared on the Lebanon 24 website under the headline “Recruitment by a new method?” which claimed dating apps such as Tinder and Bumble are increasingly viewed as unconventional communication tools that could be exploited by Israeli intelligence, including soldiers or Mossad agents, to lure Lebanese citizens by exploiting geographic proximity and lack of oversight.