The United States’ final withdrawal from the World Health Organization last week was not just another chapter in an internal political dispute over the coronavirus pandemic, China or the United Nations. It marked the culmination of a consistent policy pattern spanning both terms of President Donald Trump, during which Washington repeatedly pulled out of international institutions, treaties and agreements governing health, climate, security, culture and human rights, long considered pillars of the global order.

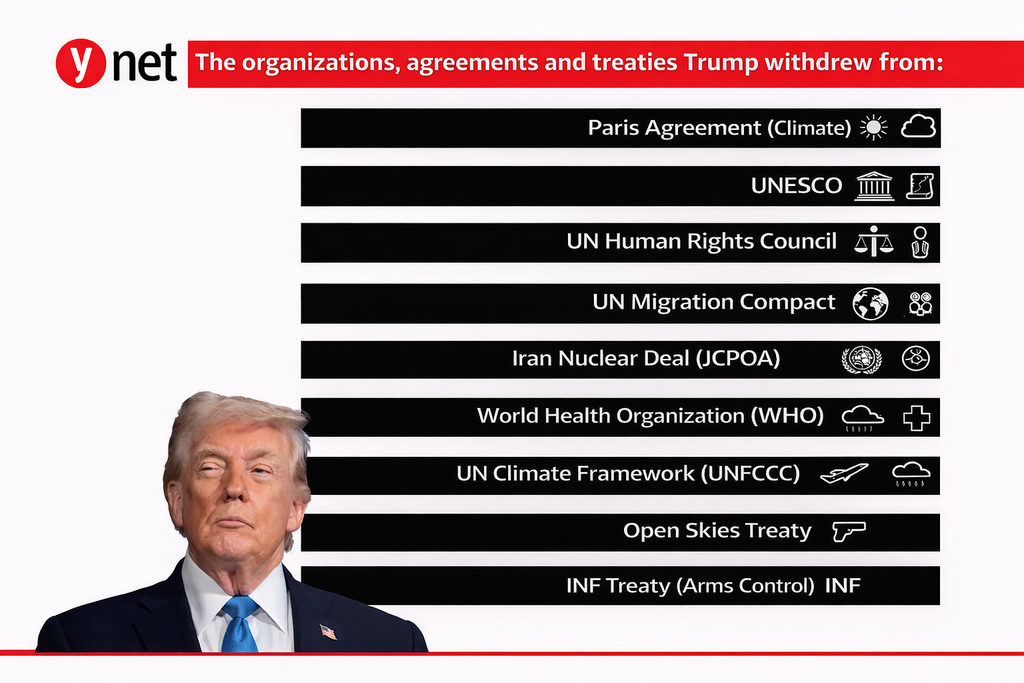

Taken together, this represents one of Washington’s most dramatic shifts away from the international institutional system since World War II. The official justification accompanying nearly every withdrawal has been similar: the organizations are costly, inefficient, politically biased, infringe on American sovereignty or serve the interests of rivals such as China and Russia. Beyond these arguments, however, the repeated decision to exit multilateral frameworks raises deeper questions about America’s role in the world, the future of the international order and the price paid not only by other countries, but by the United States itself.

First term: ‘Bad deals’ and the start of dismantling

From the outset of his presidency in January 2017, Trump made clear that Washington’s relationship with international frameworks was about to change. While his predecessors, Republicans and Democrats alike, viewed international institutions as tools to amplify American power, Trump portrayed them as constraints.

One of his first decisions was to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade agreement rather than a traditional international organization, but one with major strategic importance. The pact was designed to curb China’s economic influence in the Asia-Pacific region, and the US withdrawal created a vacuum that other countries filled without Washington. Trump framed the move as exiting a “bad deal,” but it came at a significant geoeconomic cost.

The most symbolic and widely publicized decision of Trump’s early presidency was the announcement that the United States would withdraw from the Paris climate agreement, the global accord aimed at limiting global warming. The announcement came in June 2017, with the withdrawal taking effect in November 2020 under the agreement’s rules.

For Trump, the deal burdened American industry while allowing China and developing countries to benefit from leniencies. For the international community, it was a major blow to global climate efforts and, above all, to American leadership. While global initiatives continued, the move undermined confidence that the United States was committed over the long term to rules it had helped shape. “I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris,” Trump said at the time, a quote that became emblematic of his presidency.

In October 2017, Washington announced its intention to withdraw from UNESCO, the UN’s cultural, educational and scientific organization. The stated reasons were accumulated US debt to the organization and claims of political and anti-Israel bias. The withdrawal took effect at the end of 2018 and was presented as a values-based decision, not merely a budgetary one. Beyond the Israel debate, the move signaled a retreat from a central arena of US soft power, where Washington had shaped norms in education, science and cultural preservation for decades.

Two months later, the US also withdrew from the UN’s Global Compact for Migration, a nonbinding framework intended to coordinate international migration policy. Despite its voluntary nature, the administration argued it undermined US sovereignty. The stance, reaffirmed by Trump last year, prioritized national border control and rejected international frameworks deemed incompatible with the America First doctrine.

In June 2018, the United States exited the UN Human Rights Council. Trump and his administration portrayed the council as hypocritical, composed of rights-abusing states and obsessively focused on Israel. The move was framed as a moral statement, but in practice it removed the US from the table where global human rights priorities are set, leaving room for other powers to shape the agenda. Then-US ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley called the council “a cesspool of political bias.

Security, nuclear issues and arms control

The American retreat was not limited to civilian institutions. In the security and arms control realm, the decisions were arguably even more consequential.

In May 2018, Trump announced the US withdrawal from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, formally known as the JCPOA. The agreement, designed to limit Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief, was labeled by Trump as a historic failure. The withdrawal marked a clear preference for unilateral pressure and sanctions over a multilateral monitoring and verification framework. “It’s the worst deal ever,” Trump said.

That October, Trump announced the US withdrawal from the 1987 INF Treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union, which limited intermediate-range nuclear forces. The administration cited Russian violations, but the move dismantled one of the cornerstones of Cold War-era arms control.

In 2019, Trump withdrew from the UN Arms Trade Treaty, which regulates conventional arms trade. He argued the treaty threatened the Second Amendment, even though the US Senate had never ratified it. The move was largely symbolic, but it underscored opposition to international regulation of weapons.

A year later, the US exited the Open Skies Treaty, which allowed participating states to conduct observation flights to promote transparency and confidence-building. Again citing Russian violations, Washington’s withdrawal significantly reduced oversight tools designed to prevent misunderstandings and escalation. Russia later followed suit.

Amid the coronavirus pandemic in April 2020, Trump froze US funding to the World Health Organization and later announced withdrawal from the body, accusing it of mismanagement, covering up information and favoring China. “The organization failed in its basic duty,” Trump said, accusing it of amplifying Chinese “disinformation.” The move was reversed when President Joe Biden took office in January 2021, but with Trump’s return to the White House last year, the WHO once again became an immediate target.

Second term: Wholesale withdrawal

On his first day back in office, Trump signed an executive order restarting the withdrawal process from the WHO, this time without reversal. “We’re getting rid of all the cancer of the Biden administration,” Trump said as he signed the order in the Oval Office. Last week, the withdrawal was finalized, ending US membership in the global health body.

But the WHO was only the beginning. About three weeks ago, the White House issued a memorandum stating that the United States would exit 66 international organizations and bodies it said “promote progressive agendas, suffer from mismanagement and operate against the American national interest.”

The list includes major climate frameworks such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the IPCC, the scientific body underpinning global climate policy. The move goes beyond a return to exiting the Paris Agreement and signals deeper disengagement from global climate efforts.

The list includes 31 UN agencies and 35 independent international organizations. Secretary of State Marco Rubio said the administration views these bodies as “wasteful, ineffective and harmful,” and that the US would no longer pour “the blood, sweat and resources of the American people into institutions that offer no return and threaten American sovereignty.” He explicitly cited opposition to diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and gender equality campaigns.

UNESCO has again returned to the spotlight. In July, Trump ordered the US to withdraw once more from the organization, with the exit expected to take effect by year’s end, marking another reversal after Washington rejoined under Biden.

Why Trump is doing this

The common thread running through all these withdrawals is a worldview that sees multilateralism as a burden rather than an asset. For Trump, multilateralism is not a value in itself. International institutions are viewed as arenas where the US pays more, commits more and gets less. America First is not just a slogan, but a framework in which every agreement or organization is judged by immediate gain rather than long-term systemic influence.

There is also a domestic ideological and political dimension. Criticism of the UN, climate institutions and human rights organizations fits neatly into rhetoric against “global elites” and skepticism toward experts and scientists. China serves as a unifying argument, particularly regarding the WHO and climate policy, allowing withdrawals to be framed as defenses against strategic rivals.

The cost and Trump’s world order

The cumulative impact of these exits goes far beyond any single case. In health, US absence from the WHO weakens not only the organization’s budget but Washington’s ability to shape standards, early warning systems and resource distribution in future crises.

In climate policy, withdrawal from UN frameworks undermines trust, shared targets and long-term cooperation. In security, dismantling arms control mechanisms increases uncertainty, reduces transparency and raises the risk of escalation.

Moreover, when the United States repeatedly leaves the multilateral table, it creates a vacuum others are eager to fill. China, the European Union and even regional coalitions gain greater influence in shaping rules, norms and standards. In that sense, Trump’s withdrawals do not merely reduce US involvement. They shift the balance of power in the international system. When America leaves, someone else steps in, and that someone does not always share American values.

Whether this is a stable strategy or a negotiating tactic remains unclear. Trump presents withdrawals as leverage for “better deals,” but as exits multiply, confidence wanes that the US will return and play by the same rules.

For the world, the result is a less stable international order, with more competition and less certainty. For the United States, it is a conscious choice to relinquish part of the power derived not only from military or economic strength, but from leadership and the ability to shape the global system itself. And perhaps Trump is aiming to create his own world order, beginning with the “peace council” he has proposed, which he says could one day replace the United Nations.