Welcome to Las Vegas, one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States. In the 1980s, the metropolitan area had fewer than half a million residents; today it has 2.4 million, and the city is expanding at a staggering pace.

As the city has grown, the Israeli community has surged as well. Alongside real estate developers and businesspeople who helped shape the city, young Israelis who initially arrived to work in mall kiosks and tourist zones have since begun opening small businesses or joining new commercial ventures.

Where do they live? Las Vegas is surrounded by endless desert and has almost no limits on expansion. Around the Strip, the famous corridor of hotels and casinos, new neighborhoods have been built rapidly, with wide roads, shopping centers and schools. Unlike cities constrained by lack of space, Las Vegas simply keeps building into the desert — north, south and east — nothing but sand and new construction.

The city’s major transformation began in the 1980s. Tens of thousands of families — especially from expensive California — saw Las Vegas as a more convenient and affordable place to live. Everything was cheaper: housing, food, gas, and by a significant margin. Among those “newcomers” were many Israelis, arriving mainly from Los Angeles but also directly from Israel, who began building a local community with schools, synagogues, restaurants and shops. Las Vegas is very welcoming to Israelis; antisemitism or anti-Israel demonstrations are rare to almost nonexistent.

Hebrew street names in upscale neighborhoods

Danny Itzhaki and Sam Ventura, two well-known local contractors, are responsible for building many of the city’s neighborhoods, including Summerlin, one of the most desirable and upscale areas. Do not be surprised if, while driving around East Paradise Valley — about eight kilometers from the Strip — you encounter street names in Hebrew such as Gershon, Shemtov, Tomer, Aviv and Galit.

In many U.S. cities, real estate developers who build new neighborhoods can propose street names. After municipal approval of construction plans, they submit name lists — sometimes following specific themes such as flowers or composers. That is how clusters of Israeli street names emerged.

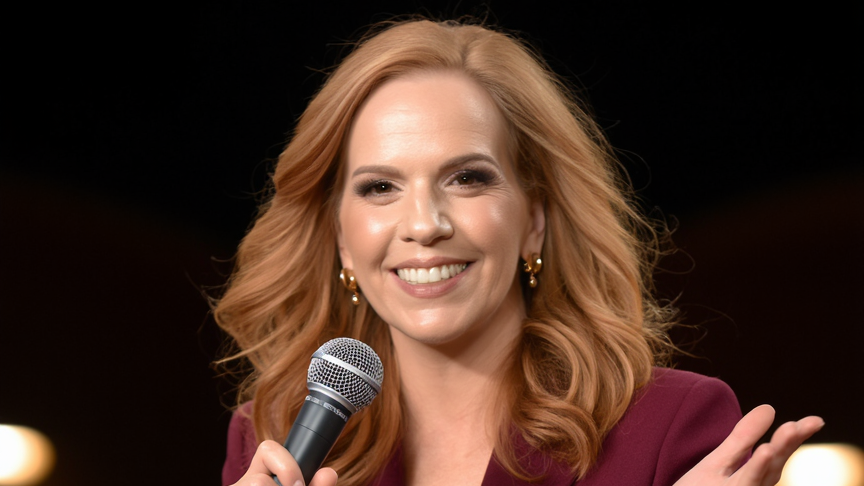

Galit Ventura-Rozen, for whom one of the streets is named, is the daughter of Sam and Rachel Ventura. She works as a real estate broker and is also a lecturer and influencer with 150,000 Instagram followers. Her parents emigrated from Israel to New York when her mother was pregnant, and Galit was born there. The family moved to Las Vegas in 1986 after five years in New York and ten in Los Angeles. She met her first husband while studying at Tel Aviv University (she is now remarried) and says she raised her three children the way she was raised — an Israeli home, Hebrew speaking, with summer visits to Israel.

“I lived between two worlds and always tried to find myself. I stood out because my parents had accents, and even my name was different from the other kids in school,” she recalls. Still, she never hid her identity; she was proud of her Israeli and Jewish background. Her license plate reads GALIT. She also gave her children Israeli names — Lior, Elad and Shimon.

“Just like me, they spent every summer in Israel. I sent them to the Adelson school through eighth grade, and their closest friends were Israelis or American Jews. Two of my sons married Jewish women, which makes me very proud. My children are continuing the Israeli tradition. When they went to university, they were active at Hillel and joined Jewish student fraternities. It is moving to see how important it is for them to stay connected to Israel and Judaism.”

“When we arrived here, there were 300 families and very few Israeli restaurants,” says Sam Ventura. “Today, there are 12,000 Israelis. Thousands arrive after the army to work in kiosks and stay. They later open their own businesses, marry each other and join the community.”

His longtime friend, Itzhaki, moved from Israel to Los Angeles 50 years ago. He and his wife tried returning to Israel in the 1980s, but after two or three years, they moved back to the United States in 1988 — this time to Las Vegas. Their daughter Sigal Shatta, an attorney, was appointed this April as the federal prosecutor for Nevada. Sigal has two brothers — Aviv, a psychiatrist, and Tomer, a real estate agent — both of whom have Las Vegas streets named after them, though Sigal is still waiting.

Sigal and Galit met in school, and thanks to their parents, became close friends. Despite growing up in the United States, both speak fluent Hebrew, and their children (Sigal has two and Galit has three) are also Hebrew speakers.

Maintaining identity

How do Israelis preserve their cultural identity in the world’s gambling capital? Sam explains: “It all starts with the parents. If parents care enough to keep the flame alive, then the children will care too, and they will keep their identity.”

Sam and Danny did quite a bit to ensure that. They understood that the future of the second and third generations depended largely on them. Together with several Israelis in the community, they founded the Or Bamidbar synagogue, funding everything out of their own pockets. They also established a nearby Jewish community school that served 100 students, until one day Sam received a call from the late businessman Sheldon Adelson, asking him to close the school and transfer the students to the Hebrew Academy in Summerlin.

The Hebrew Academy was founded in 1990 by Milton Schwartz, a wealthy Jewish donor, and between 2006 and 2008 it expanded significantly thanks to contributions from Sheldon and Dr. Miriam Adelson. The school was later renamed in their honor. “Sheldon was a good friend of mine for many years. His children studied at our school,” Ventura says.

Since running a school is expensive, it did not take Ventura long to understand that Adelson’s request was the right step. Adelson wanted to provide his children with a strong Jewish education, and for him, investing in the school was the natural way to ensure it.

“Most of the students received substantial scholarships, so the school didn’t generate income,” Ventura says. “Every two weeks when payroll came around, I would call Sheldon and say, ‘Hey Sheldon, I’m short 25 thousand dollars.’ And he would call his secretary and say, ‘Betty, Sam needs money, send a courier now.’ And every two weeks I’d receive 25, 30, even 40 thousand.”

The Adelson campus is the largest Jewish school campus in the United States in terms of land area. It spans 3.5 acres and includes sports fields, a pool, a theater and more. Despite its size, the number of students is relatively modest — about 600 from pre-K through 12th grade.

It can feel unusual to see such a large and luxurious Jewish school in a city with a relatively small Jewish population, but that is what happens when it is backed by billionaire philanthropists. At the campus entrance stands a massive Israeli flag visible from afar, and every morning begins with the singing of Israel’s national anthem.

Continuing to serve in the IDF

Noa Peri-Jensch, vice president for communities at the Israeli-American Council (IAC), says the school is the reason she decided to stay in the city after moving there 16 years ago with her husband and two daughters. The plan was to remain for only a year, but the moment she walked through the campus gates she realized it was the place she wanted her daughters to study. “I remember a Kabbalat Shabbat ceremony at the school and I couldn’t stop crying. I was so moved and felt like I had come home. We had many opportunities to leave for work reasons, but the school is what kept us here.”

Noa soon founded the local Israeli Scouts troop together with other Israeli parents, which is how she met Dr. Miriam Adelson, whose son was a member. Adelson is arguably the most famous Israeli in Las Vegas and a beloved figure in the community.

Noa, the mother of two daughters, organizes many events through the IAC together with Ofra Etzion, director of the IAC Vegas branch, including Adloyada Purim Parade, Independence Day celebrations, lectures and networking events for Israeli professionals. Her daughter Lia, who recently completed nearly four years of military service, came to visit with her boyfriend. They will soon return to Israel, where she plans to study at Reichman University and likely remain afterward.

“Lia didn’t spend a single day of her life in Israel before she enlisted,” Noa explains. “We lived in Greece at the time, where we worked in hospitality, and I flew to Israel just to give birth to her, then returned. I did the same with my second daughter.” Noa believes the Scouts played a big role in Lia’s decision to enlist.

‘Money doesn’t grow on trees, you work hard’

As the Israeli community has grown, Israeli restaurants have opened, including Jerusalem Chef’s Table, Shawarma Vegas and Casa Mia, along with kosher supermarkets such as Kosher Market. Chef Eyal Shani also opened the restaurant HaSalon at the Venetian Hotel (which was owned by the Adelsons until 2021, when they sold the hotel and the adjacent Palazzo for $6.25 billion).

In addition to kosher dining, synagogues are easy to find. According to Ventura, 27 synagogues — Ashkenazi and Sephardi — are active in the city. Or Bamidbar added Chabad to its name after a Chabad rabbi from New York, Yossi Shochat, joined the congregation and has become a draw for many Israelis.

“With so many young Israeli families moving to the city, the rabbi trained as a mohel, and every week he performs a brit milah,” Ventura says.

And what about the casinos? Poker and roulette tables hold little appeal for most members of the Israeli community. They long ago learned that Las Vegas was built on the money of vacationing gamblers who drop hundreds or thousands of dollars and then go home. So if you hear Hebrew in a casino, it is likely from visiting Israelis, not local residents.

Kiosk work attracts many young Israelis, but not all stay in that field. Over time many leave to start their own businesses, mostly stores selling cosmetics, jewelry and souvenirs. Others move into real estate and construction, and in recent years cyber and high-tech professionals have joined them thanks to the city’s growing tech infrastructure.

About six months ago, a new restaurant opened in Summerlin: Café Landwer. It quickly became popular with both Israelis and Americans. Amir Mor, who opened it, moved to the city a year and four months ago with his wife and three children.

The move came partly at his wife’s urging — she wanted to relocate to the United States — and when the opportunity arose to open a branch of the restaurant in Las Vegas, he seized it.

One thing Amir enjoys is the ease of getting around. “In Israel, I commuted daily between Haifa and Tel Aviv. Here, there’s no traffic and everything is close. There’s also a large Israeli community with many people from Haifa. We quickly made many connections and friendships, and four months after arriving we celebrated our daughter’s bat mitzvah with more than 100 guests.” Two of his children attend public school; the youngest goes to the Jewish school, Zaccor. His wife teaches at the Adelson school.

As for the cost of living, Amir says Las Vegas is cheaper than Israel. “Most things are much cheaper here, like gas — we save about 10,000 shekels a year on gas for our two cars. Some things are more expensive, like fruits and vegetables, but other products, like meat, are cheaper. We heard Las Vegas has become more expensive in the past two or three years. The house I live in was bought 10 years ago for $400,000; today it’s worth $900,000.”

Are they planning to stay in Las Vegas?

“I don’t know. They say you need at least two years to decide, and I agree. People in Israel think money grows on trees here, but it doesn’t — you work hard. Fortunately, the restaurant is doing great and the Israeli community is supportive. The problem in America isn’t necessarily loneliness — we have many friends. The difference is that in Haifa, I knew all the neighbors four houses down and four houses up. Here I’ve lived for over a year and don’t know the person next door.”

Financial incentives for businesses and freelancers

Las Vegas is popular in part because of its significant tax advantages. Nevada has no state income tax, allowing families and professionals to keep more of what they earn. Property taxes and other rates are relatively low, and the city offers economic incentives for businesses and the self-employed. The result is that more people see Las Vegas not only as a leisure destination but as an economic opportunity — a place where you can enjoy high quality of life, invest in real estate or run a business while keeping more profit compared with high-tax states.

That said, new residents need to remember it is a very hot desert city in summer. From June through August, and sometimes in September, temperatures exceed 40 degrees Celsius, with last summer’s peak reaching 44.5. Nights are cooler but still very warm.

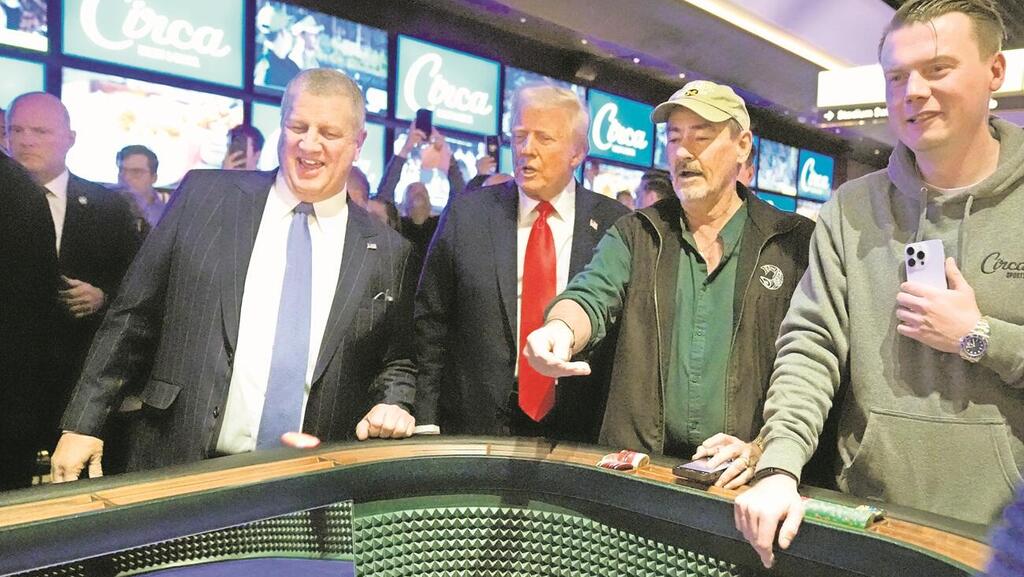

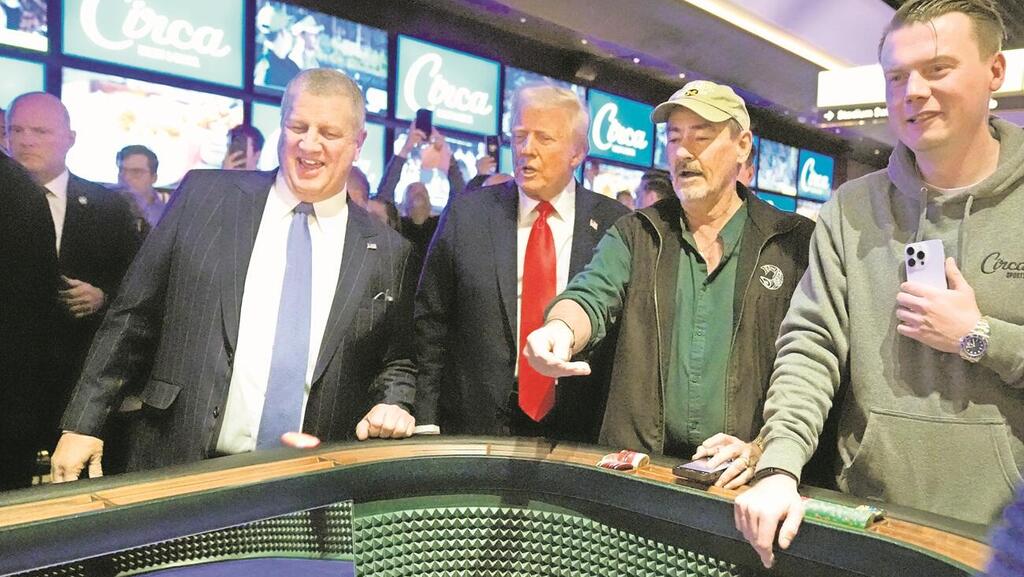

7 View gallery

United States President Donald Trump at a casino in Las Vegas

(Photo: Mark Schiefelbein/AP)

In addition, the city has little natural greenery and limited options for outdoor recreation unless you “pretend” and hop from “Paris Las Vegas” to the Venetian’s canals or the classical Rome setting of Caesars Palace.

Nevada’s public school system is known to be challenging and is ranked 46th out of 50 in the United States. The good news is that parents can enroll their children in the Adelson private school, though even with scholarships it is still a significant expense.

The city can also feel relatively monotonous for residents uninterested in nightlife and casinos. While dazzling at night when the casinos are lit up, many locals find the cultural and social offerings limited — few museums, theaters or diverse community events compared with other major cities.

Still, the Israelis I met love the city and see in it the ideal balance between a strong community life and a calmer, more relaxed lifestyle compared with other large American cities.