On the hills of Sheikh Abreik, not far from the site where Nvidia’s new and gleaming campus will soon rise in Kiryat Tivon, Alexander Zaid stood nearly a century ago and gazed into the future. The present was nearly unbearable, even for a hardened pioneer like him. Friends died around him like flies, some from malaria, others from despair or longing for the Diaspora. Zaid himself nearly died countless times while fighting Arab attackers who targeted his isolated family farm. Yet Zaid clung to the land with near messianic determination, long before real estate became a profitable commodity.

“When he was here on the farm, he was alone. Imagine ten years here alone. It was incredibly hard,” says his granddaughter, Tali Zaid Reva, a tour guide from Moshav Beit Zaid, which borders Tivon and was founded by her grandfather. She never met him. Zaid was murdered when her father was just 18. “At some point Giora, the eldest son, told him, ‘Dad, what will be? How long can this go on? We are alone here. Until when?’ And my grandfather answered him, ‘Giora, one day they will fight here over every dunam.’”

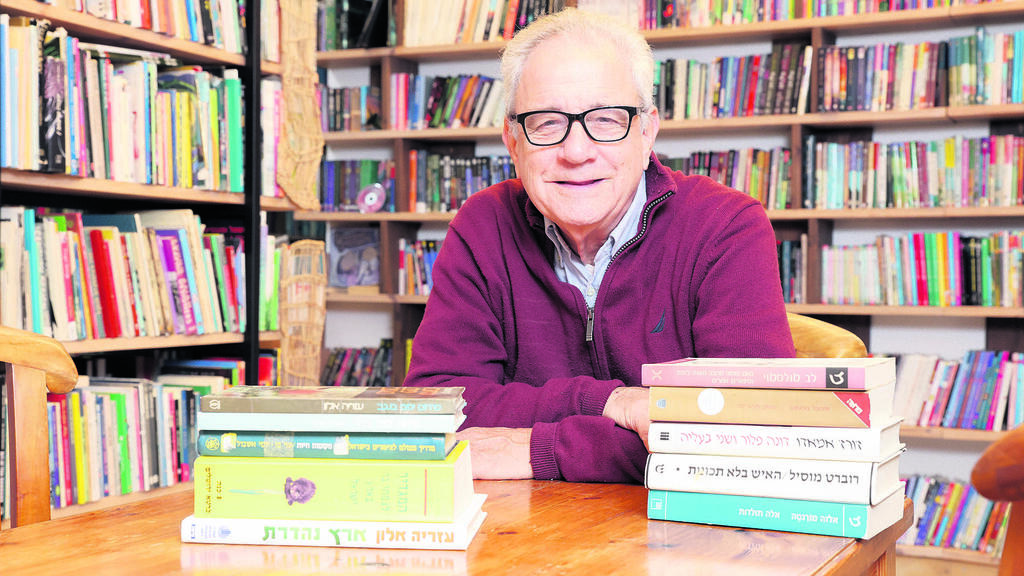

5 View gallery

Tali Zaid Reva beside the statue of her grandfather, Alexander Zaid

(Photo: Elad Gershgoren)

A beautiful story.

“Today they are not fighting over a dunam, they are fighting over every meter,” she says. “My grandfather foresaw that this area would become settled and highly desirable.”

What would your grandfather say about Nvidia entering his territory?

“I am sure he would have been happy, even though agriculture was his central value. He learned that from Herzl. To solve the Jewish problem, Jews had to return to the plow,” she says, sighing. “But that was 150 years ago. Things have changed. Agriculture has lost its magic.”

Speaking of agriculture, what happened to the family greenhouses?

“We sold everything. In the 1990s the industry collapsed for many reasons, dollar rates, fuel prices. Agriculture was a family tradition, but it is a very hard profession. And honestly? Maybe we were not such great farmers.”

Location, location, location

Anyone who climbs to Zaid’s iconic statue will discover that little remains of the pioneering ethos beyond the landscape itself. The valley is still a dream today, but the fervor of working the land has been replaced by the all Israeli craving for income producing real estate, and lots of it. The year 2025 will be remembered as the year Zaid’s prophecy fully came true, when Nvidia, a $3.4 trillion company whose chips power the artificial intelligence revolution, announced that Kiryat Tivon would become its Middle East stronghold.

The figures are staggering. A 90-dunam campus. 160,000 square meters. 10,000 employees. Completion is planned for 2031. “Israel has become Nvidia’s second home,” declared founder Jensen Huang. Israel is Nvidia’s largest development center outside the United States, with more than 5,000 employees. The Tivon campus will double that number. Dozens of municipalities competed to host the American tech giant. Haifa, Yokneam, Nesher, Migdal HaEmek, Afula, Harish, Netanya. All courted Nvidia with proposals and promises.

5 View gallery

The land designated for Nvidia’s planned campus in Kiryat Tivon

(Photo: Elad Gershgoren)

So why did Tivon win?

Location, location, location. Proximity to Nvidia’s current headquarters in Yokneam and the data centers in Mevo Carmel. Ready land zoned for high tech industry. Access to Highway 6 and rail. And proximity to a robust electricity grid, a critical issue for AI server farms that consume power like small cities. But Naftali Shoshani, a proud resident and social activist, offers a broader geopolitical explanation. “This place has always been a crossroads,” he says. “The Ottoman Valley Railway passed here. The oil pipeline from Iraq passed here. Now Highway 6. Big things have always passed through this point. Not to mention Ramat David airbase and Haifa.” In short, forget the Abraham Accords. Get ready for the Nvidia Accords.

A bubbling town

On a rainy weekday afternoon, Kiryat Tivon is not buzzing with excitement. It is simmering with bitterness in endless traffic jams, raising questions about how the town’s modest infrastructure will handle thousands of additional cars each day. The only visible sign of enthusiasm is a scattering of signs welcoming the new neighbors with charming naivety. “Nvidia, you chose right. Welcome to Kiryat Tivon.”

The council building itself is empty. But council head Ido Grinblum is energetic enough for an entire platoon of civil servants. Surprisingly young at 39, still riding the euphoria of Nvidia’s announcement, some say he has national political ambitions. “All of us here will say in a decade, we were there when this started,” he says. “We will be the northern Silicon Valley of Israel. We will offer a counterweight to the center.”

And what does Tivon get in return?

“There is no exit here,” Grinblum says. “Municipal tax revenue will be seven million shekels a year. I am not dismissing that, but it is four percent of the council budget. It will not make Tivon economically stable.” The state and the council granted Nvidia significant concessions. The company will pay about 90 million shekels for the land instead of several hundred million. Municipal taxes were also cut by about 50 percent.

“Their structure is not a building. It is a spaceship. You do not build something like that to hide it behind a hill. They wanted something that when you drive through the north, you say, ‘That is Nvidia.’ And that is what they will get.”

During our visit, a terror attack in the Jezreel Valley killed two Israelis, but personal security does not seem to trouble the Americans. “They are more concerned about transportation, infrastructure, and the oil refineries,” Grinblum says, stressing he does not speak for the company. “Lawlessness does not worry them. That exists everywhere.”

What is their vision?

“What they imagined resembles their California campus. Something exclusive. Their building is not a building, it is a spaceship. You do not build a spaceship to hide it behind a hill. They want something visible. They want people driving through the north to say, ‘That is Nvidia.’ And that is what they will get.”

A bubble at any cost

In the renderings attached to Nvidia’s press release, the planned structure, a massive triangular building modeled after the Santa Clara headquarters, sits against a lush rural backdrop that, to put it gently, does not quite resemble Tivon. “This is economic colonialism. Conquering space through capital. The Chinese excel at this,” Shoshani says. Grinblum is unfazed. “In an ideal world, I would want my daughter to keep skipping through the meadow and for there to be no construction at all. But that is not how the world works.”

Construction will begin next year, adjacent to Tzel Oranim, Tivon’s newest neighborhood, filled with generic apartment blocks far removed from the old town’s rural character. The neighborhood sits in a green valley between Tivon’s eastern slopes and Oranim College to the south. To the north lies a citrus grove and an open field. To the west flows the Kishon River, where a promenade and bike path are being built. With enough money, even the Kishon can become an attraction.

Verd Lichner, who owns a real estate brokerage and development firm, said, “These Nvidia people have finished me. Every minute the phone rings. They want to invest, invest. People think they have discovered some kind of trick.”

“The campus will serve as a magnet for leading tech companies and residents from across the region,” the council’s website proclaims. “The plan includes 120,000 square meters of employment, hospitality, dining, conference halls and retail.” But not all residents share the council head’s optimism. “Ido deserves credit for destroying Tivon’s fabric,” one resident wrote on Facebook. “Many of us have no desire for growth. Development should mean preserving and improving what exists according to the town’s spirit and the residents’ wishes. This project is a disaster.” Another added, “This is the beginning of the end of Tivon as we know it. It will push out anyone who cannot afford rising rents. There is no room to increase housing supply to meet the demand.” And one resident summed it up neatly. “You turned Tivon into Tel Aviv, just with more trees.”

Squares, hippies and hipsters

Legends abound about Tivon’s contrarian locals. “Kiryat Tivon has always been a bubble,” Zaid Reva says. “When they wanted to build a country club, people objected because ‘it would be bad for them.’ Every initiative meets opposition. Even a traffic light was controversial.” The same is happening with Nvidia. “Tivon residents do not want anyone touching anything. They want life to stay exactly as it is.”

That instinctive opposition does not mean they are always wrong. A study conducted for ynet found that the housing market is unprepared for the coming wave of demand. Estimates suggest prices could rise by 15 percent in the immediate Tivon area within three to four years, and by 7.5 percent in the second ring.

Tali Zaid Reva, granddaughter of Alexander Zaid, said, “I am sure he would have been happy about it, even though agriculture was his central value. But that really was 150 years ago, and things have changed.”

At the legendary Legenda ice cream shop, Ron and Timna, new arrivals studying healing therapies, observe the town. “Tivon has groups,” they say. “Squares, anthroposophic hippies, hipsters, people who left the center after the pandemic, young people with tattoos and dogs, some religious, and recently evacuated kibbutz residents from the north.” Long before Pardes Hanna, there was Kiryat Tivon.

Founded in 1958 from the merger of Tivon, Kfar HaNevi’im and Beit Zaid, the town rejected a single identity from day one. Anthroposophists arrived in the 1970s and turned Tivon into a Waldorf education powerhouse. Today, a third of local children attend alternative schools. “Quality education and community culture are why people want to live here,” says Gilad Alon, a local cultural figure and environmental activist. “Local government does not always understand that.”

The market moves faster than the spaceship

Change, however resisted, is inevitable. Crime spilling over from neighboring Basmat Tivon and the national political rift have already shaken the town. And while Nvidia’s project is still in early planning stages, the market is already racing ahead. Speculators are buying. Investors are calling nonstop. Central Israel buyers are eyeing land and imagining trees cut down.

“The Nvidia people have finished me,” sighs real estate broker Vered Lichner. “Every minute someone calls to invest.” She grew up in Tivon. “My father always said there is no more beautiful place in the world. I believe the same. So do my children.” She recounts a recent encounter. “A couple came to buy land in the wadi. The woman looked at the trees and said, ‘We need to cut everything down.’ I told her, ‘Sweetheart, get in the car, drive to Kaplan Street and buy there. There are no trees there.’” “We have to preserve Tivon’s character. There are very few places like this left. Green like this. That is our greatness.”

In 2011, when Cupertino residents asked Steve Jobs what Apple would give back to the community, he answered with three words that perfectly capture ruthless capitalism. “We pay taxes.” Nvidia, at least rhetorically, promises more. Partnerships with schools. Local employment opportunities. But when asked for concrete commitments, numbers, budgets, timelines, the answers are vague. “It is still too early,” Grinblum admits. And perhaps that is the problem. Because while Nvidia is still planning, the market has already landed. The spaceship has not yet arrived. The shockwaves already have.