Today, diplomatic or strategic cooperation between Israel and Iran seems almost unthinkable—especially in the wake of Operation Rising Lion and the events of October 7, 2023. But for two decades, during the 1960s and 1970s, Israeli architects, engineers and construction firms played a key role in shaping Iran’s built environment. They helped design and construct neighborhoods, factories, hotels, luxury towers and even major infrastructure projects—including Tehran’s urban sewage system, now back in the news.

“In our time, the hostility between the State of Israel and the Islamic Republic of Iran seems fixed and unchangeable,” opens a 2017 exhibition catalog from the Israeli Architects’ House Gallery. “But during the 1960s and ’70s, the two nations maintained diplomatic and commercial ties—though not always official or public.”

The exhibition, titled Building a New Middle East: Israeli Architects in Iran Under the Shah, examined this unlikely chapter of regional cooperation. Since Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, relations have turned hostile, but many of the buildings and infrastructure developed by Israelis still stand.

The New Middle East vision famously outlined by Shimon Peres in the 1990s, in fact, had a precursor decades earlier in a very different form. “The relationship with Iran was important for Israel, which believed it could help forge a new regional balance through cooperation with non-Arab states—Iran, Turkey and Israel,” said Dr. Neta Feniger, who studied the topic for her doctoral research.

“Even if Israel wasn’t directly responsible for the diplomatic ties, it worked to sustain and strengthen them—not only as a partner in modernization, but also because Iran was virtually Israel’s sole oil supplier at the time.”

Architecture as diplomacy

In the 1950s, Iran formally recognized the State of Israel, which in turn assisted Tehran with security and technological development projects. The professional ties formed in these areas paved the way for Israeli-led construction and design initiatives within Iran.

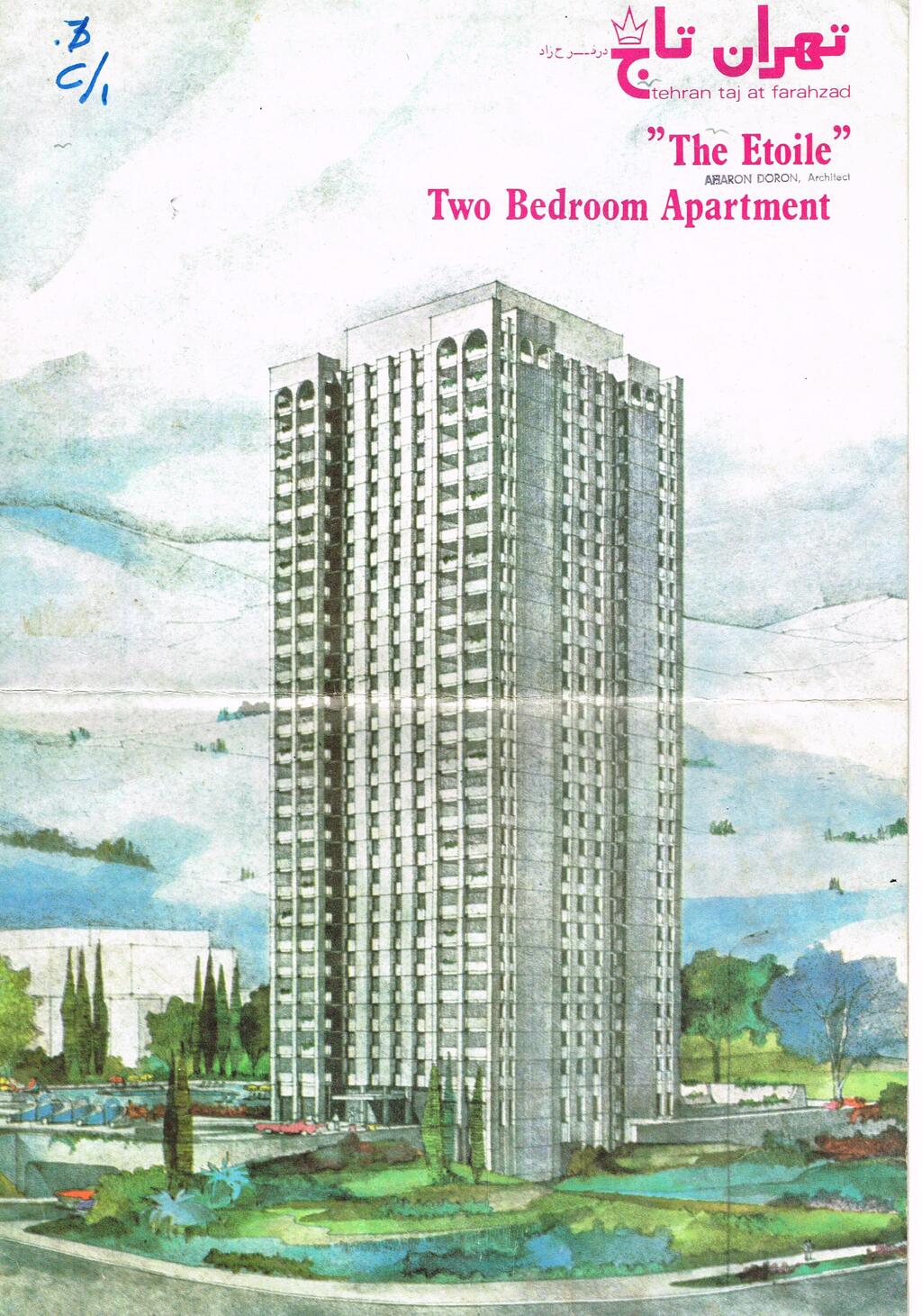

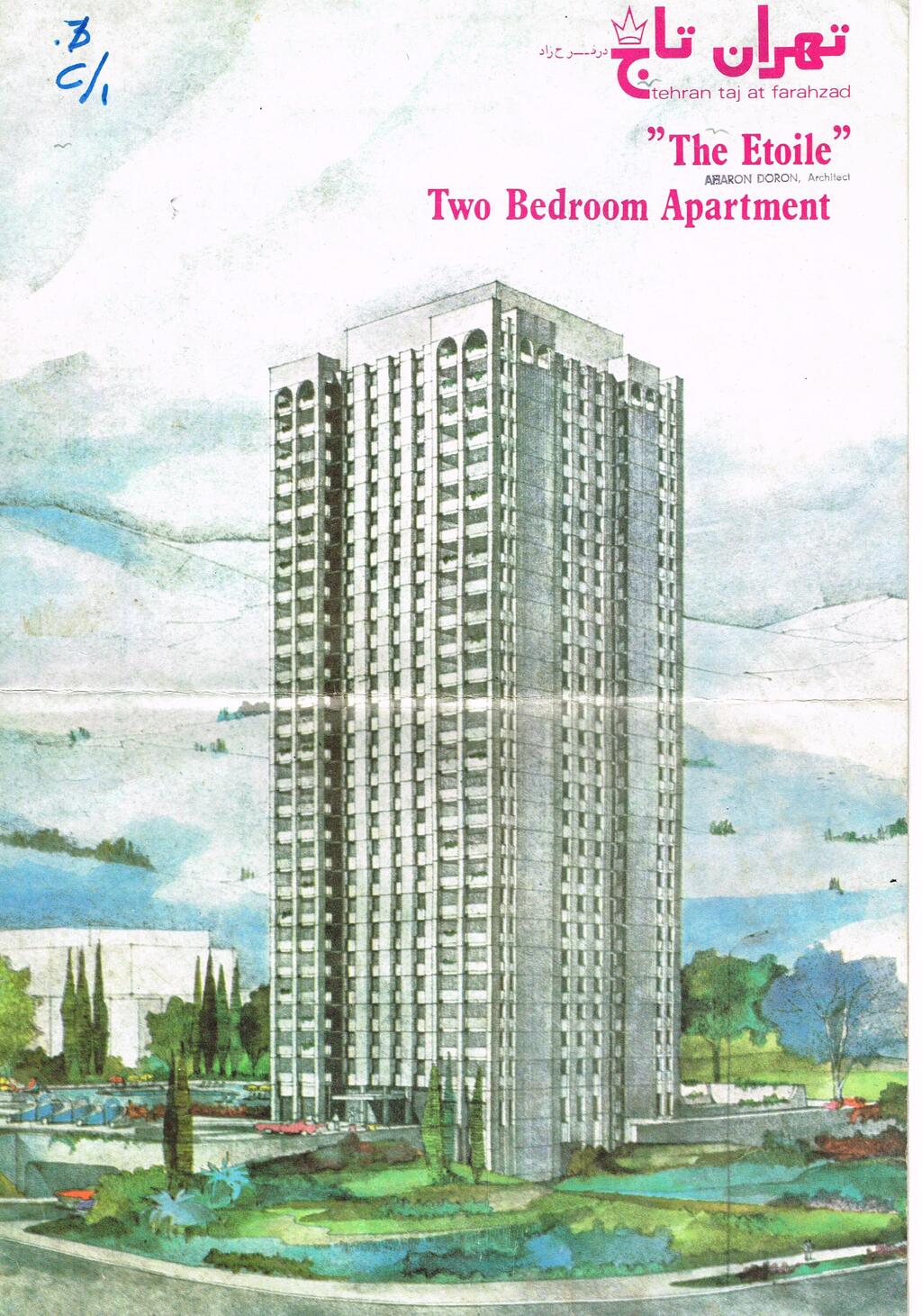

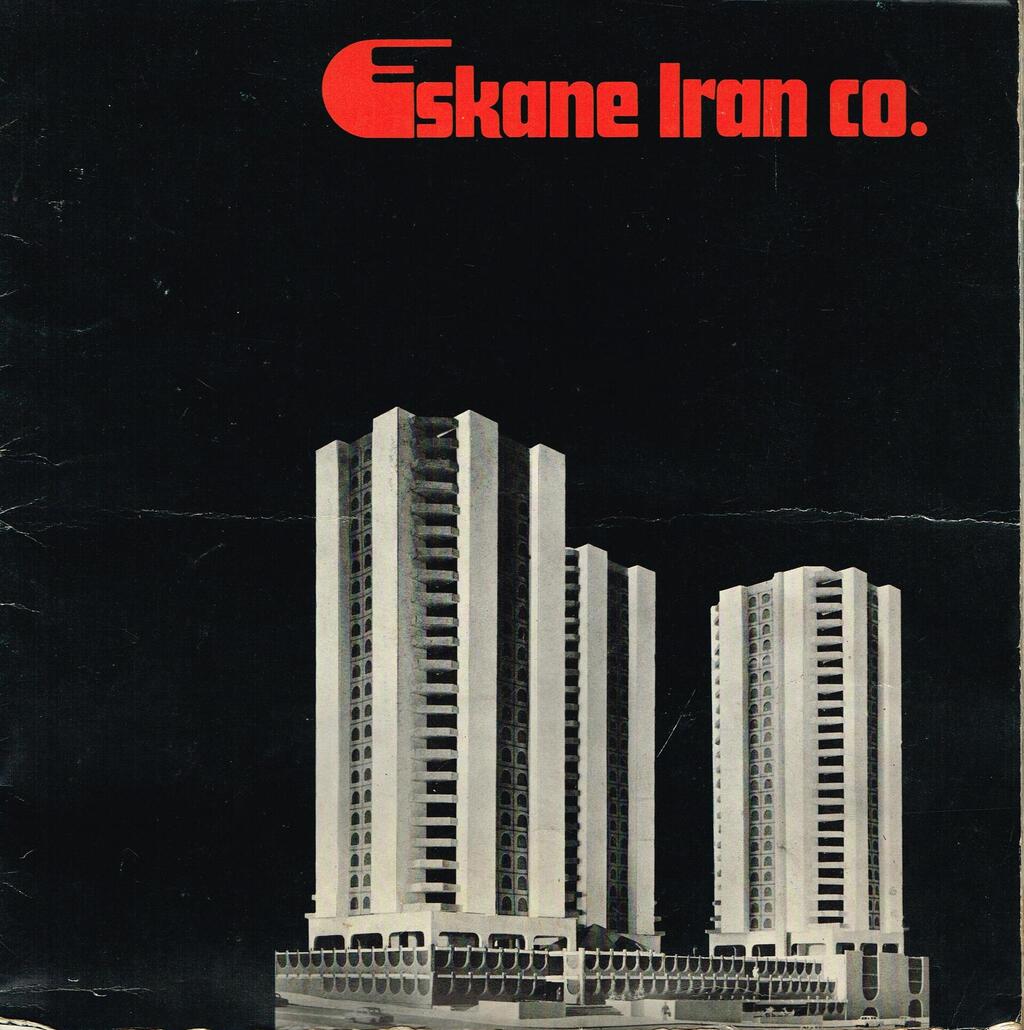

8 View gallery

From the 1977 promotional brochure for the Tag Towers in Tehran, designed by Aharon Doron

(Photo: Courtesy of Israel Architecture Archive)

“In effect, Israel strengthened bilateral relations through the export of architectural and engineering knowledge,” explains Dr. Feniger. This effort aimed to build trust between the countries by contributing to Iran’s physical and infrastructural development, leveraging Israel’s rapid post-statehood experience in mass housing construction.

Israeli architects worked alongside their Iranian counterparts, not to impose ideological values or because of a lack of Iranian expertise, but largely for economic reasons. “They went to make money, not to make architecture,” Dr. Feniger stresses, noting that Israeli involvement in Iran stemmed primarily from commercial interests and market opportunities.

The first Israeli architectural project in Iran began in 1962 at the initiative of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who ruled from 1941 to 1979. The Shah, seeking to modernize Iran’s rural landscape, launched several development efforts, though a major earthquake that same year delayed the initial project. It was Israel’s offer of humanitarian assistance in the disaster’s aftermath that solidified the countries’ cooperation. “It’s hard to imagine today, but under Iran’s former regime, there was no opposition to Israelis—they knew how to form connections and seize collaborative opportunities,” Feniger adds.

Throughout the 1960s, Israeli companies like Solel Boneh and others undertook extensive infrastructure projects in Iran, including sewage systems, plumbing networks and bridge construction, all involving Israeli engineers. Archival plans and documents from these projects—if they survived the 1979 Islamic Revolution—are now housed in Israel rather than in Iran.

According to Ynet's sister publication Yedioth Ahronoth, Iranian officials discreetly reached out in the early 2000s via a third party to request the original plans for Tehran’s sewage system, designed by Israeli firm Tahal, in order to fix persistent malfunctions. Unconfirmed but unrefuted rumors suggest they received the files. Today, however, images of raw sewage flowing in Tehran’s streets raise questions, possibly pointing to either neglected maintenance or even sabotage.

Israeli architect Dan Eytan designed housing for Iranian soldiers

In 1972, the Iranian regime launched a project to transform two Persian Gulf fishing towns into military bases, according to Dr. Feniger. As part of the initiative, residential neighborhoods were needed to accommodate Iranian navy personnel and their families in the southwestern cities of Bushehr and Bandar Abbas—strategically located along the Strait of Hormuz, now frequently in the headlines for entirely different reasons.

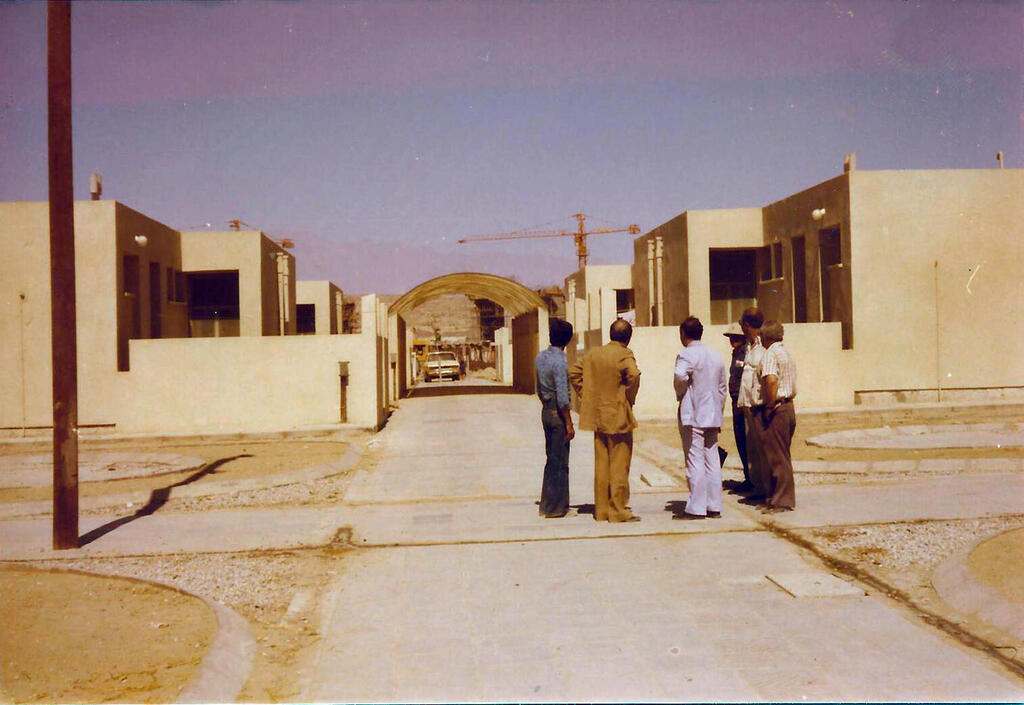

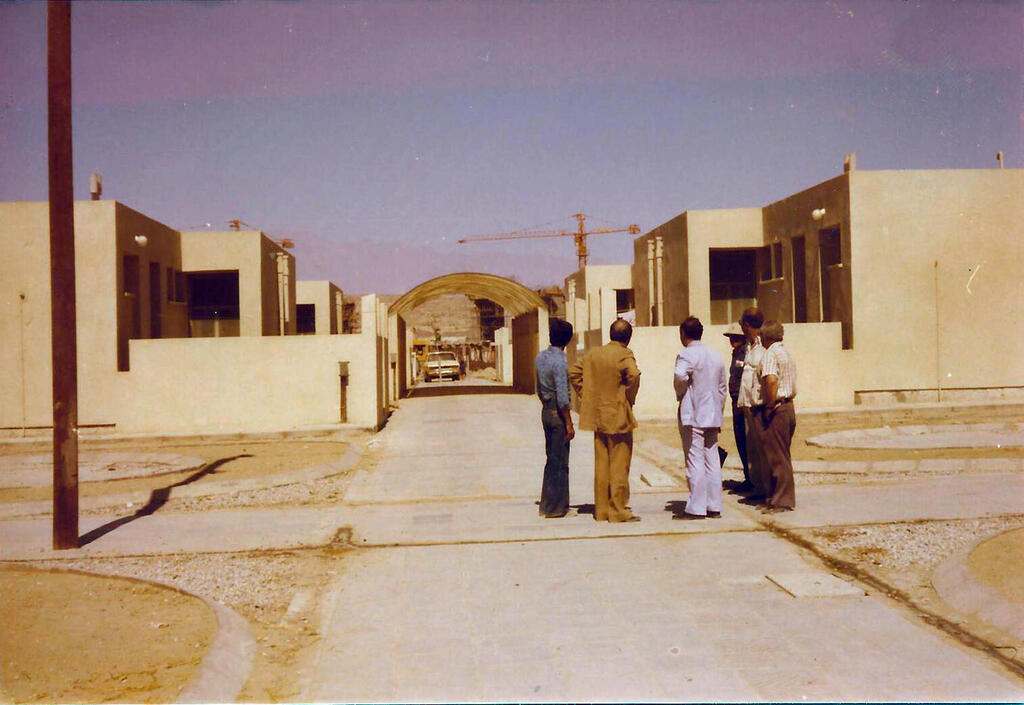

8 View gallery

Buildings in Bandar Abbas. The Israeli team presents the construction to Iranian navy officials

(Photo: Moti Blayer)

Building on prior Israeli-Iranian cooperation, Iranian officials invited renowned Israeli architect Dan Eytan (1931–2023) to design the military housing. Eytan, whose credits include the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the Mexico Building at Tel Aviv University, worked with engineers from the Israeli firm Engineering Services and construction company Rassco, which was established by the Jewish Agency and helped build numerous towns across Israel, including Kfar Shmaryahu, Batzra, Bnei Zion and housing developments in Tel Aviv, Haifa and Holon.

The project consisted of two large residential neighborhoods originally planned for around 1,200 housing units. By the time planning was underway, the scale had expanded tenfold, reaching a budget of $1.25 billion, according to Eytan at the time. The neighborhoods reflected modernist design principles: orthogonal traffic axes, 16-story residential towers, four-story blocks enclosing internal courtyards and detached private homes—all with a minimalist, functional design. Unit sizes ranged from 128 to 240 square meters.

Dr. Feniger notes that Eytan was deeply invested in understanding Iranian culture—not through decorative motifs, but through functional choices that matched local lifestyles. The project also emphasized adaptation to climate and seismic risk.

8 View gallery

Architectural model of the buildings in Bushehr

(Photo: Courtesy of Archiect Dan Eytan)

Eytan, in an interview for an exhibition catalog, said climate considerations were central to the design process. Covered walkways connected residences and commercial areas; walls were insulated and recessed windows were used to reduce direct sun exposure, all enhancing the project’s resilience and comfort.

Air conditioners, drip irrigation and kitchens from Israel in Tehran

From a Western perspective, the late-1970s oil embargo triggered an economic downturn—but in Iran, it spurred rapid economic growth and urbanization, especially in Tehran. During that time, the Iranian government opened its doors to architects from around the world, including Israelis, to help plan its expanding cities.

For Israeli architects and builders, this was a golden opportunity during a recession back home. Those who relocated to Tehran for work with Israeli construction firms enjoyed a high standard of living and were exposed to a thriving building sector with scales and resources previously unseen in Israel.

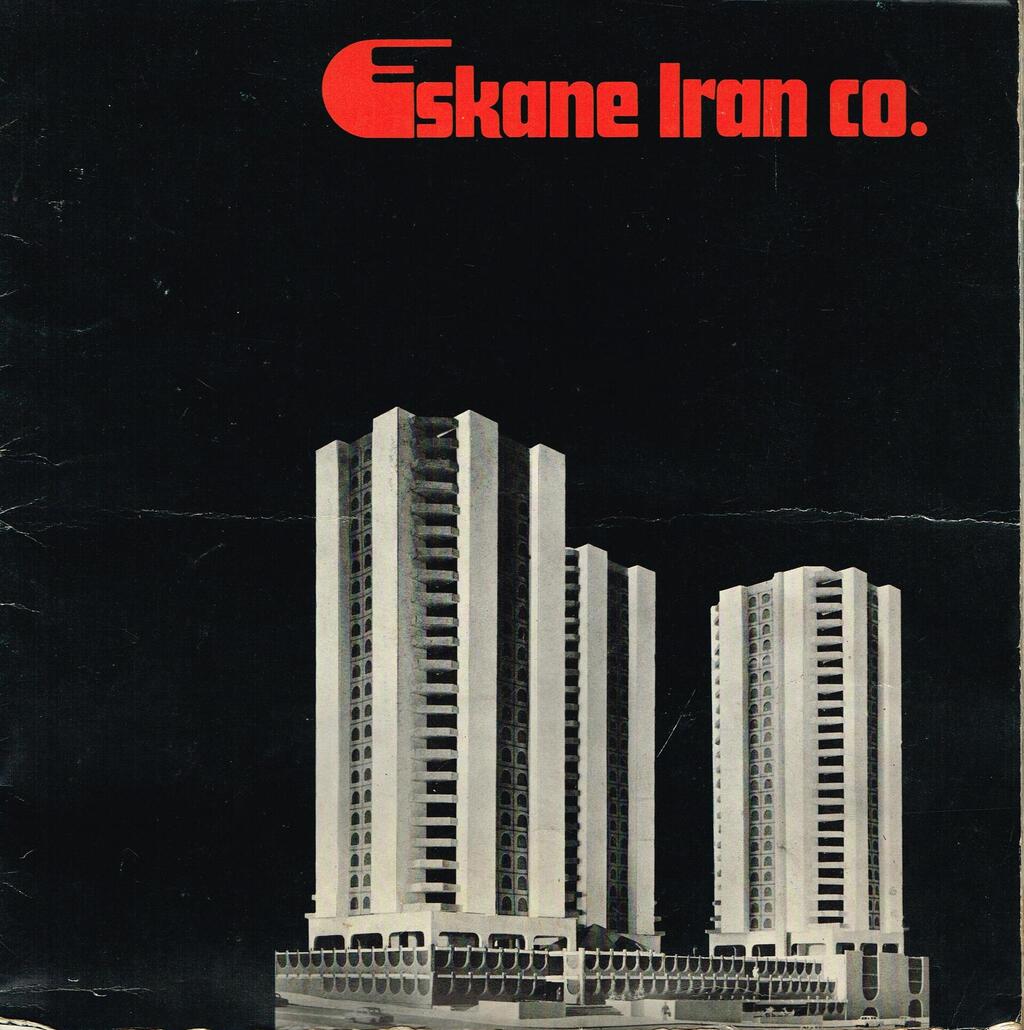

8 View gallery

From the 1972 promotional brochure for the Askan Towers in Tehran

(Photo: Courtesy of Israel Architecture Archive)

Among the major developments of that era were luxury high-rises, about 30 stories tall, built in central Tehran by two Haifa-based architects working for the Israeli firm Solel Boneh. Residential floors were constructed above five commercial podium levels housing malls and retail spaces.

At the time, these heights and construction methods were unprecedented in Israel. Since steel was readily available in Iran but unfamiliar to Israeli builders, they designed the structures in concrete, which required massive foundations—economically and structurally unnecessary, but technically safer from their perspective.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Unlike the 1970s Israeli ethos of cost-effective, resource-efficient housing, the Iranian approach aimed to market and sell high-end apartments. As a result, beyond architects and construction teams, the projects also included air conditioning units from Israeli company Tadiran, kitchen installations by Regba and irrigation systems supplied by Netafim.

Neoliberal real estate ideas came from Iran

Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Israelis—viewed as aligned with the West and the Shah’s regime—were forced to leave. Many of the planned developments stalled, required new architects or were scrapped altogether.

Among the unrealized proposals were a project by Arieh Sharon (1900–1984), known as “Israel's architect,” a tower designed by Ram Karmi (1931–2013), who later worked on the Tel Aviv Central Bus Station and Habima Theater renovation, and a residential neighborhood by Zalman Enav, known for his work at Shenkar College and Bar-Ilan University.

Though the revolution began as a popular uprising against the Shah’s repression of the Iranian middle class, by early 1979—with the return of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini—it became a religious revolution. Israelis were no longer welcome in what had become the Islamic Republic. The two countries, once partners, became open adversaries, now engaged in a state of war.

Israeli professionals who returned home brought with them new experience and business practices aligned with the emerging ethos of neoliberalism—concepts that, to this day, shape aspects of Israel’s real estate market.

8 View gallery

From the 2017 exhibition at the Architects’ House, Israeli Architects in Iran Under the Shah

(Photo: Eran Tamir-Tawil)

“Despite perceptions of Iran as a developing country, the projects Israeli architects worked on were unique and large-scale,” says architect Eran Tamir-Tawil, who co-curated a 2017 exhibition on the Israeli architectural presence in Iran. “The exhibition aimed to ask questions about the cultural meaning of this cooperation—especially the interplay between local architecture here and there.”

In retrospect, Tamir-Tawil concludes, “There wasn’t deep cultural dialogue, but working in Iran gave Israeli architects exposure to a scale of construction not seen in Israel at the time—an experience that later drove a leap forward back home.”