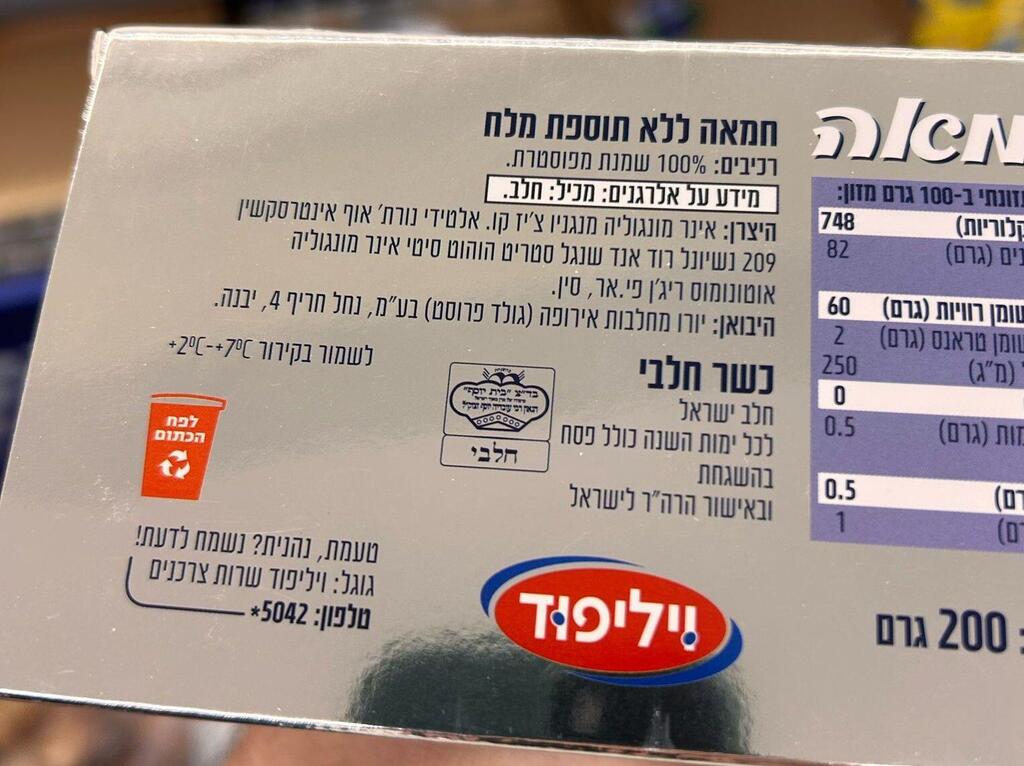

Importers are exploring new countries for sourcing goods to address the halt in exports from Turkey to Israel and rising prices. Following the arrival of pasta from Azerbaijan, consumers have noticed that the Osher Ad retail chain is now selling butter imported from Mongolia by Willifood. Meanwhile, the Victory retail chain recently began selling ketchup and mayonnaise from Malta.

These countries are inexpensive sources for imports—Mongolian butter, for example, is significantly cheaper to import compared to butter from Denmark, Belgium, or France. Recently, butter imported from Lithuania has also arrived in Israel. The ketchup from Malta is being sold for $1.35 for 550 grams, which is less than $0.25 per 100 grams. This is a competitive price compared to branded ketchup, which typically costs between $0.45 and $0.53 per 100 grams.

However, other retailers are running promotions on private-label brands, such as Rami Levy, which offers 750 grams of ketchup for $1.32 during sales, as opposed to the regular price of $2.13. This private-label product is made in Israel. Retailers that don’t offer private-label brands told Ynet: “Victory’s move is nice, but kids will always prefer Osem and Heinz.”

Under the Strauss Ice Cream brand, Unilever is now selling Twister popsicles, which were previously produced in Turkey. These are now imported (with slightly different flavors) from Greece. “Greece has increased its food exports to Israel because its flavors are similar to those in Israel and Turkey. For Unilever’s popsicles, the production location doesn’t matter much, as the product is essentially identical worldwide, just made at a different factory. That said, Magnum bars imported from Turkey had a slightly different taste compared to those produced in Israel, primarily due to the difference in the milk used there.”

One of the challenges with sourcing from new countries is ensuring kosher certification. While the non-kosher market benefits from a wide variety of imports, most Israeli consumers buy kosher food, which dominates the market. An importer explained to Ynet: “There are countries like the United States and the United Kingdom that have local and international kosher certification organizations recognized by the Israeli Rabbinate, which makes the process easier. Then there are countries like Portugal, Croatia, or Thailand, which have local kosher committees or rabbis who provide certification.

And there are countries like Argentina where importers are already accustomed to sending kosher supervisors. For example, importing chocolate from Poland is straightforward because there’s already an established import process from there. Another example: most of the canned corn currently sold in Israel comes from China. This is possible because there’s a local rabbinate there, alongside a Badatz (kosher certification) in Hong Kong. There’s also an intention to import olive oil from Portugal, a country that currently has a significant Israeli presence.”

“But even in these countries, there are nuances. For instance, birch juice soda imported from Russia might be kosher, but a similar product from Germany could suddenly be non-kosher. In one case, a Badatz organization in France certified a protein shake produced in Germany, but the Israeli Rabbinate rejected it because they didn’t recognize the certifying body.”

“The main issue lies in countries where kosher organizations haven’t yet established a presence, kosher supervisors haven’t been sent, and local factories are unfamiliar with kosher standards.”

Zwi Williger, owner of Willifood, told Ynet: “I stopped importing butter from Mongolia mainly because it’s challenging to send rabbis there for kosher certification. Recently, I attended a food exhibition featuring producers from various countries, including dairy products from India. Now, we’re considering India for importing dairy products like butter and cheese. I’m currently evaluating whether their products meet international standards.”

“Our goal is to find quality products at good prices for consumers. For example, we sell grated Gouda cheese for $3.94, while competitors sell it for $6.58.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

A representative from another company explained: “There’s a difference between a trader and a brand marketer. Traders can sell various products and stop importing them if they don’t perform well or switch to another source. They spot opportunities, which can be either long-term or one-time.

“In contrast, a brand is typically produced at a single manufacturing site or a few sites that maintain consistent quality and recipes. For example, Willifood markets a brand called Euro for cheeses, but it hasn’t always ensured consistency in imports. A salty cheese under the brand could come from Turkey one time and Cyprus another, meaning it’s not necessarily the exact same product. This leads to competitive pricing, of course, but it doesn’t always build consumer loyalty because the question becomes whether consumers return to the product and whether it maintains the same taste quality.”