German media in recent weeks have been consumed by a public debate over a proposal to curb or effectively abolish part-time work, exposing deeper divisions over work culture, gender roles and national identity.

Supporters of the idea argue that Germans must work longer hours to strengthen Europe’s largest economy, contending that too many employees have opted for reduced schedules. Critics counter that a better work-life balance enables people to work more efficiently in four days rather than five.

For many workers — particularly mothers, who make up a large share of part-time employees — reduced hours are not a lifestyle choice but a necessity. Germany faces a shortage of daycare centers, forcing many women to stay home longer or limit their working hours.

The economic wing of the conservative party of Chancellor Friedrich Merz is pushing to restrict part-time employment, with proposed exemptions for mothers of young children and people caring for elderly parents.

Beyond labor policy, the debate reflects a broader ideological clash. Merz and many members of his party have called for a return to what they describe as an older German work ethic — one that helped rebuild the country’s economy and restore its global standing after the devastation of the Nazi era. The vision emphasizes professional fulfillment and sees one’s occupation as a central component of personal identity.

Opposing them are many younger Germans, particularly from Generation Z, who seek more flexible lifestyles and place greater emphasis on personal well-being. Some say they prefer fewer working hours and lower salaries over dedicating additional time to corporations.

The proposal has drawn opposition not only from advocates of strict separation between work and private life but also from employees in sectors often criticized as insufficiently productive. Workers in fields such as education, nursing, social work and elder care — professions dominated by women — argue that the issue is not hours worked but inadequate compensation.

“There are few sectors where there is such a large gap between the level of commitment and the financial reward,” Anna Schmidt, a nursing worker from Duisburg, told the television network NTV. She noted that workers in her field demonstrated full dedication, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, despite relatively modest pay.

The power in workers’ hands

Despite employees’ legal right to request part-time work, many employers can refuse such requests on operational grounds. Yet part-time arrangements can also benefit employers. International studies have found that part-time employees do not suffer reduced productivity, report higher job satisfaction, experience less stress and sleep better.

Germany, however, is in the midst of a severe economic crisis. The country must once again tighten its belt to avoid deeper economic turmoil, particularly amid the rise of the far-right Alternative for Germany party — a combination that has prompted comparisons to Germany in the late 1920s. Germany needs more workers, yet in the third quarter of 2025 the share of part-time employees reached a record 40.1% of the total workforce. What has alarmed supporters of restricting part-time work is not only the figure itself, but the fact that one-third of part-time employees chose that status voluntarily, rather than due to a lack of full-time positions or caregiving obligations.

Here too, Germany’s much-criticized bureaucracy is slowing reforms that many argue the labor market urgently needs. The debate centers on updating employer-employee standards that were shaped by Germany’s post-World War II reconstruction — standards that critics say no longer fit today’s global economic reality. They do not reflect Germany’s diminished economic strength, evolving workplace needs on the employer side, changing expectations among employees, or the digital revolution. Discussions about revising these standards and introducing greater flexibility in working hours began as early as the 2010 reform debates. Once again, bureaucracy appears to be the only clear winner.

At the same time, as in any economic system, supply and demand shape labor relations. Because Germany — and much of Europe — faces a shortage of workers, especially skilled labor, the starting point in negotiations between employees and employers now tilts clearly in favor of workers. Corporations need employees and must pay accordingly. In the past, bargaining largely revolved around wages. Today, workers increasingly focus on other demands, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic: workplace mobility, the ability to work from home and flexible hours.

Many economists argue that a shorter workweek benefits the economy. In their view, economic growth is not strengthened by sheer volume of work or output, but by the value generated during working hours. More leisure time for employees translates into additional spending — on shopping, vacations and tourism — which they see as key drivers of economic activity.

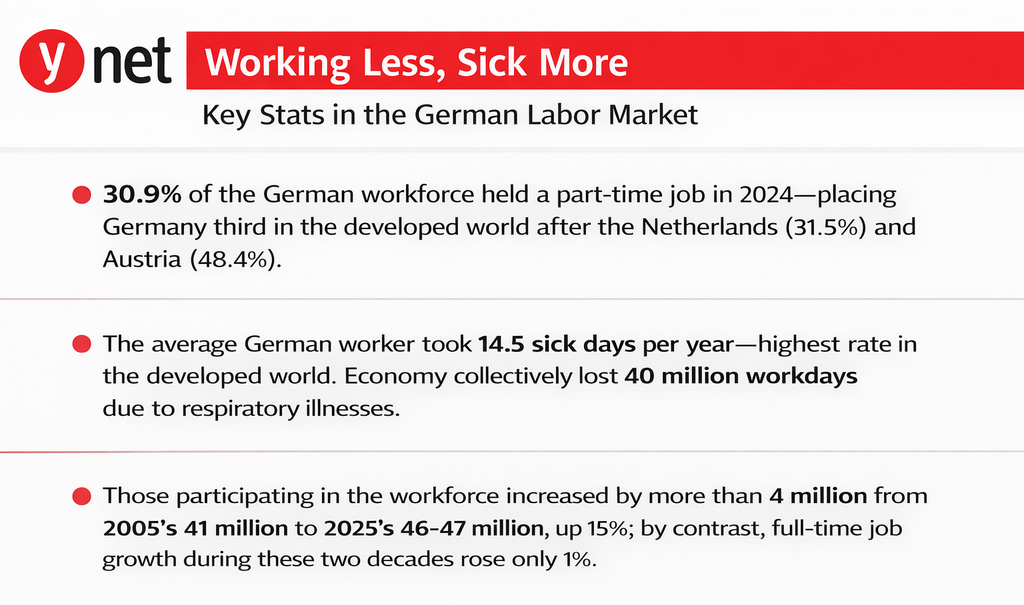

Economists aligned with the ruling party disagree. They argue that part of Germany’s economic and industrial decline stems from weak motivation and a diminished work ethic. With 30.9% of the workforce employed part-time in 2024 — third in the industrialized world after the Netherlands (48.4%) and Austria (31.5%) — Germany faces another challenge: it leads in absenteeism due to sick leave. The average German worker misses 14.5 workdays per year because of illness, more than 2% higher than in any other Western country. The cost to the German economy, excluding the burden on health insurers, is estimated at about €40 billion annually. It is little wonder that politicians from the ruling party have proposed canceling national holidays, while the Health Ministry and Merz himself are considering scrapping the practice of obtaining sick leave certification via telephone consultation.

The divide runs deep. Conservative parties argue that those who are able to work more must do so and should not rely on a strained welfare system to subsidize leisure and lifestyle preferences. Social Democrats and left-wing parties counter that many workers in Germany are already at the limit of their capacity, and that further pressure would lead to burnout and ultimately harm productivity and the broader economy.

The following figures illustrate the anomaly of Germany’s labor market: Over the past two years, an average of about 46 million residents were part of the workforce — more than ever before. That represents an increase of 6 million, or 15%, compared with 2005. Yet total hours worked between 2005 and last year rose from 56.3 billion to 61.4 billion hours — an increase of less than 1%. Germany has far more workers than in the past, but a much larger share of them work part-time.

The challenge is likely to intensify over the coming decade as the baby boomer generation retires, creating a reality in which a smaller, less intensively working generation must finance pensions, welfare and long-term care for a large retired population. Under current conditions, Germany may consider itself fortunate if that proves sustainable. Restoring balance and renewed economic prosperity may have to wait.