Until the invasion of Ukraine, Russia's primary war against the West was reflected in efforts to push Middle Eastern refugees into European Union territories (mainly from Belarus into Poland) and in extensive efforts, aided by tens of thousands of bots, to spread fake news and disinformation online. This was aimed at sowing fear in the West and deepening its divisions.

Since the war began, the Kremlin has added two main elements: recruiting and deploying criminals in the West to create chaos (such as in cases of car burnings in Germany that were falsely attributed to climate activists) and the increasing use of mobile oil tankers as tools to break the embargo against it. These oil tankers drop anchors to the seabed, aiming to damage undersea communication and internet cables that connect countries and continents. In other words, Russia is making a massive effort to return Europe and the West from the digital age back to the analog era.

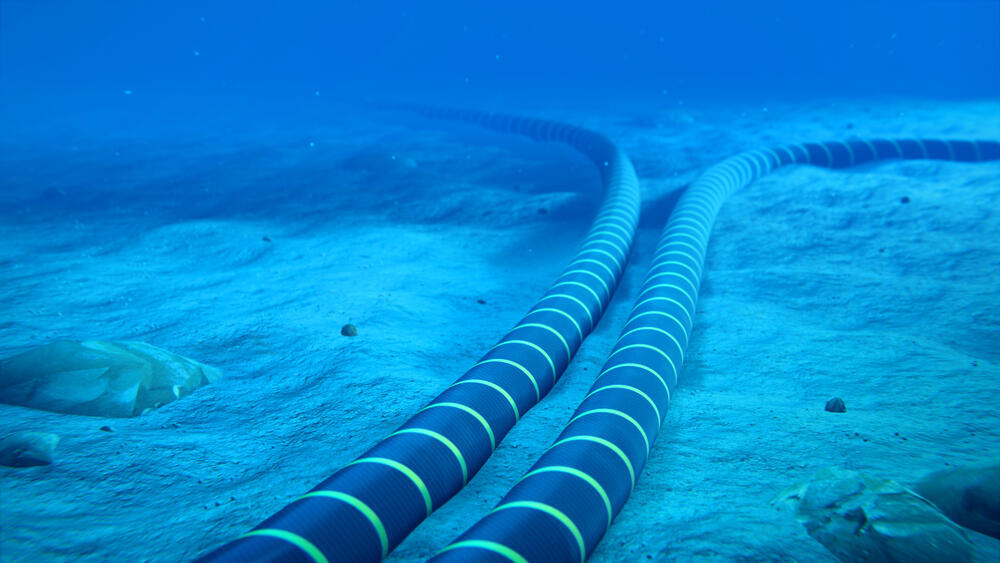

There are two types of undersea cables: 532 optical communication cables spanning millions of miles that transfer data between countries and continents, handling 95% of the world’s communication (including financial transactions worth $10 trillion annually), such as emails, video calls, and landing pages. The second type of cables is used for transferring electricity. This is a relatively new and much smaller market but is rapidly developing thanks to its ability to easily transfer renewable energy.

The cables are built in layered structures of various materials designed to protect the fibers from damage occurring in the ocean depths. It is estimated that, with proper maintenance, they are meant to last 25 years. However, repairing damage to these cables or fibers is a complex and arduous task. Often, the damage occurs accidentally, caused by fishing boats or natural factors, but a significant portion is due to intentional sabotage.

Since most of the sabotage occurs in the Baltic Sea, it is suspected to be Russian in origin. However, there have also been cases of sabotage worldwide, indicating China is also involved in efforts to damage undersea cables.

In November alone, three Russian ships (operating under different flags but with Russian captains and crew) were intercepted near damaged cables off the coasts of Sweden, Finland, and Ireland. Ireland, in particular, is home to the European headquarters of many major tech companies, including Google and Microsoft, making it a hub for processing and transferring vast amounts of data through these cables, and thus a target for Russia's hybrid sabotage efforts.

From the Russian perspective, this is the perfect crime: no war machines, minimal manpower, no traces left behind, and far greater damage to the Western world than any missile in their arsenal could cause. Additionally, since companies aim to prevent accidents and enable navigation around the cables, information about the cables is relatively accessible to the public. To make matters worse, the damage caused by such sabotage is something Western forces and countries have no real way of defending against.

The shift toward artificial intelligence technologies makes these cable networks even more critical for the digital business and communication world. Undersea fibers enable greater bandwidth and fewer delays in data transfer. Since this infrastructure is also considered more efficient in combating the climate crisis, it is no surprise that major corporations are investing significant resources to enable global coverage. Enter Russia, aiming to disrupt Western progress, alongside terrorist organizations like the Houthis, who at the beginning of last year dropped an anchor to the seabed in the Red Sea—where 90% of the information between Europe and Asia passes—and damaged cables by dragging the anchor across the seabed for miles.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

The damage is multifaceted: power outages, slower internet speeds, significant disruptions to goods transportation, decreased productivity, and harm to the reputation of companies and businesses. In Tonga, for example, a volcanic eruption in January 2022 damaged its communication cable, leaving the country disconnected from the world for nearly an entire month. These cables are the pipelines through which the two main components of artificial intelligence (electricity and data) flow. It is no surprise, then, that one of the fastest-growing industries in this field is the development of companies dedicated to securing these cables or creating alternatives for communication even after the main cable has been damaged.

Annalena Baerbock, Germany's outgoing foreign minister, stated that these acts of sabotage are a wake-up call for Europe. NATO has also established a special force to patrol and protect underwater infrastructure from ships attempting to damage cables. But this is not enough, and the problem is not solely a European one: in January, damage was caused to undersea communication fibers off the coast of Taiwan, likely by a Chinese ship.

China is suspected not only of sabotage for geopolitical reasons but also for economic motives. Until 2021, three companies—one each from Japan, the United States, and France—controlled 87% of this market. However, in recent years, a Chinese company has taken over an 18% market share, primarily thanks to massive government subsidies that allowed it to submit much lower bids than competitors from free markets.

This is, therefore, the largest and most invisible war in the world: Russians want to sabotage the Western world, Chinese aim to dominate a share of this market, and terrorist organizations seek to inflict damage. The Western world is grappling with all of these challenges while trying to build more and more infrastructure to support digital progress. Donald Trump already initiated a communications war against China and Chinese companies, but he has yet to launch the opening shot in this current battle. It will happen. Anyone who wants to know who will win the global war needs to follow the events unfolding miles beneath the ocean's surface.