In a late-night vote Monday, the Knesset passed a significant amendment to its Contract Law, overturning a decades-old legal precedent that gave judges broad discretion in interpreting contracts.

The move marks a major shift in Israeli contract law, aligning it more closely with a textual approach that prioritizes the written language of agreements over broader contextual interpretation.

The amendment, approved in second and third readings during a sparsely attended session, effectively nullifies the 1995 “Aprofim Ruling,” a landmark decision issued by then–Supreme Court Chief Justice Aharon Barak. That ruling had become a cornerstone of what critics later dubbed Israel’s “constitutional revolution,” a legal era marked by assertive judicial review and broad interpretation of laws and contracts.

Under the Aprofim precedent, courts were instructed to consider both the written terms of a contract and external circumstances, such as negotiations, intent and conduct of the parties, as a single interpretive process. Barak held that a court’s goal should be to uncover the “true and mutual intent of the parties,” even if that intent diverged from the language used in the contract itself. When the contract’s text clashed with the parties’ presumed intent, the latter was to prevail.

Supporters of the new amendment say it restores commercial certainty and legal clarity by placing the contract’s language at the center of interpretation—unless the parties have expressly agreed otherwise. Critics of the Aprofim approach had long argued that it created unpredictability in business dealings, undermining confidence in contractual enforcement and complicating risk assessments in Israel’s legal environment.

Under the revised law, contracts will now be interpreted “as determined by the parties,” and the default approach will give greater weight to the plain wording of the contract.

While the legal reform is rooted in contract law, it also carries wider implications for Israel’s judicial philosophy, especially as debates continue over the balance between legislative authority and judicial discretion.

The original 1995 ruling by Chief Justice Barak stemmed from contracts signed by the Housing Ministry with several construction firms, including a company called Aprofim. The contracts included financial incentives and a government guarantee to purchase unsold apartments. When Aprofim delivered its construction more than a month behind schedule, the government withheld 6% of the agreed payment per unit.

Aprofim sued for full payment, and the Jerusalem District Court ruled in its favor. But the state appealed, and the Supreme Court—led by Barak—overturned the decision in a 2–1 ruling. The majority held that the contract should be interpreted based on its purpose, not its wording, and accepted the government’s argument.

Nearly three decades later, as the government advanced sweeping judicial reforms, Justice Minister Yariv Levin and Knesset Constitution Committee Chair Simcha Rothman introduced legislation to amend the Contract Law.

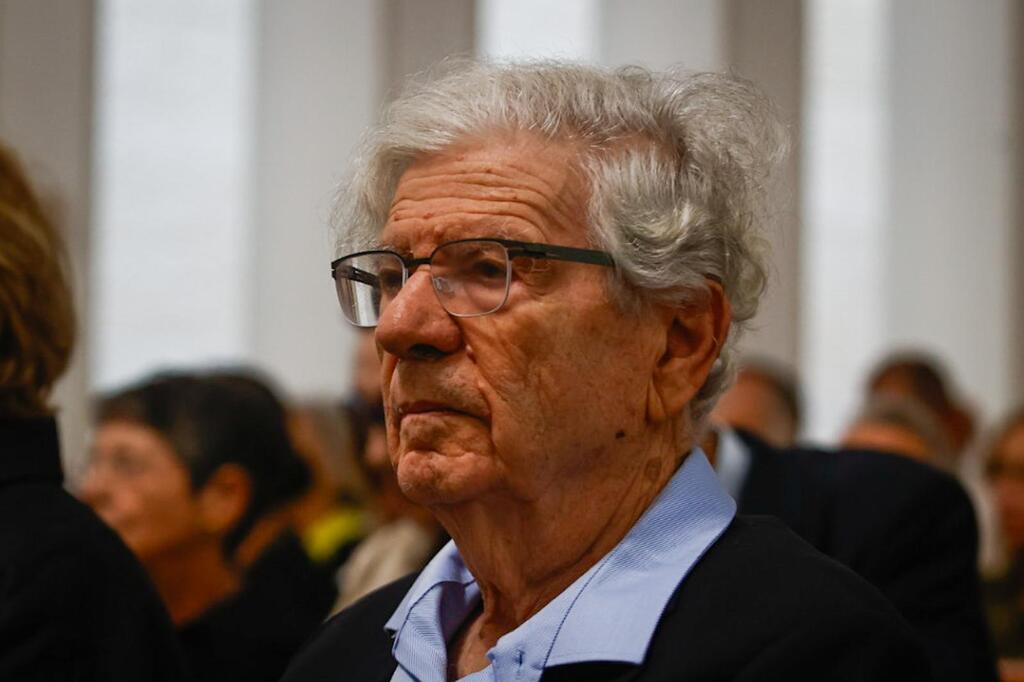

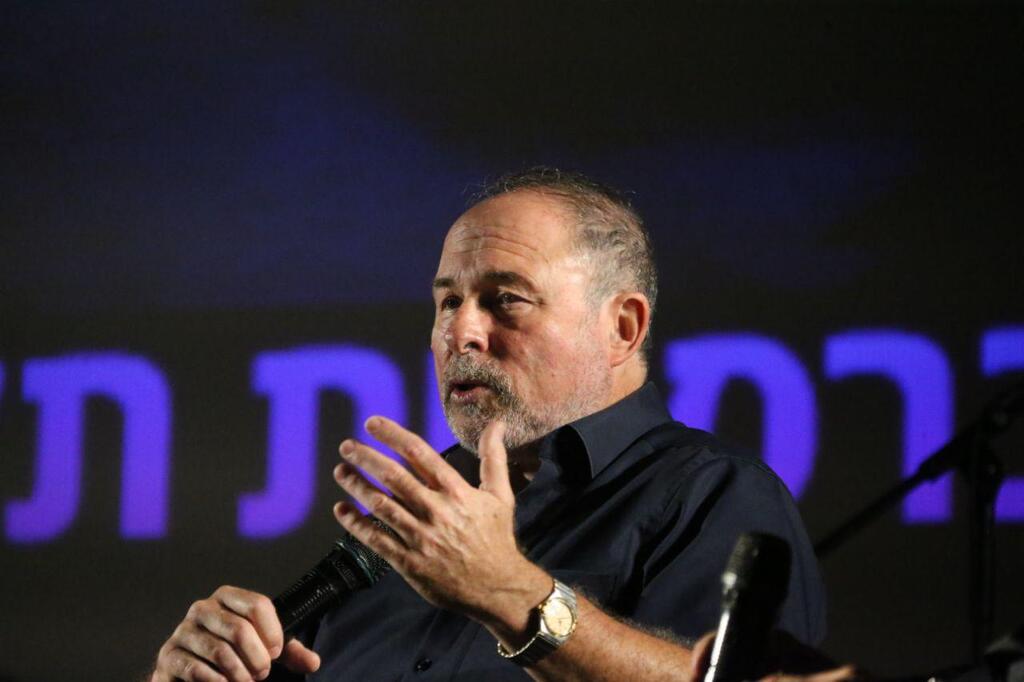

4 View gallery

Knesset Constitution Committee Chair Simcha Rothman and Justice Minister Yariv Levin

(Photo: Alex Kolomoisky)

On September 11, 2023—one day before the Supreme Court held a high-profile hearing on limiting judicial review—they unveiled the draft, proposing that both contract interpretation and the types of admissible evidence be determined by the agreement of the parties, unless they are unrepresented or the contract is a non-negotiable standard form.

Under the newly approved law, if the parties have not specified how their contract should be interpreted, different rules will apply based on the contract type. Business contracts will be interpreted strictly by their text, unless that leads to an unreasonable outcome or internal contradictions. Other contracts, such as employment agreements, collective labor contracts and standard-form contracts, will be interpreted based on the presumed intent of the parties, as derived from the contract itself and its surrounding circumstances.

The reform thus introduces a split system of contract interpretation: one rule for commercial agreements, and a more flexible approach for personal and non-negotiated contracts.

The amendment to the Contract Law—officially titled Amendment No. 3 to the General Part of the Contract Law—passed the Knesset with 18 lawmakers in favor, four opposed and two abstentions. The law redefines how courts weigh the contract’s language against external circumstances, using a set of guiding factors that includes the relationship between the parties, any information gaps or special trust, the level of detail in the contract, the parties’ professional experience and the extent of legal counsel during drafting.

The first serious judicial challenge to the Aprofim precedent came from retired Supreme Court Justice Yoram Danziger, who had been nominated to the bench by then–justice minister Daniel Friedmann. Danziger, one of the rare private sector attorneys appointed to the court in recent years, argued in his rulings that when the language of a contract is clear and unambiguous, it should be given decisive weight in its interpretation.

The official explanation accompanying the legislation emphasized that the goal is to tailor interpretive rules to different types of contracts, distinguishing between commercial and non-commercial agreements. “The purpose of the proposed amendment is to establish interpretation rules suited to business contracts versus others,” the text stated, “in line with trends in case law that recognized the need to differentiate between contract types. This is intended to enhance legal certainty in the business world and reduce court overload.”

Levin, who led the legislative effort, called the reform a “historic breakthrough for the business sector,” arguing that the Aprofim ruling created “total uncertainty” in contract interpretation. “It led to situations where judges retroactively decided what the parties had meant, contrary to the contract itself and even, at times, to the parties’ own claims,” Levin said.

“That created legal uncertainty, more litigation, increased transaction costs and even pushed businesses to place jurisdiction outside of Israel. This reform will reduce unnecessary disputes and ease pressure on the courts.”

Rothman added: “There’s no such thing as a perfect contract, just as there’s no perfect law. The sword of Aprofim, in its various forms, hung over Israeli contract law for years. Even past attempts to challenge it never reached the depth and public engagement we achieved with this proposal. Until now, courts intervened and stripped parties of their basic freedom to contract. The debate over truth versus stability will continue, but this law reaffirms that the parties themselves, not the court, are sovereign in defining their relationship.”