In the recently released film Marty Supreme, now screening in Israel, winning rave reviews and considered a contender for an Academy Award, Timothée Chalamet plays Marty Mauser, a character inspired by Marty Reisman, a Jewish table tennis player and hustler. In that sense, after portraying Bob Dylan, the Jewish Chalamet trades a guitar for a table tennis paddle while embodying Jewish cultural icons.

This is not a biopic or a faithful portrait, but a tribute to Reisman, who was not only a top-level table tennis player but also an entertainer, author, dandy and compulsive gambler, a man who spent his life seeking recognition and meaning and is receiving it now, 13 years after his death.

Reisman was born in 1930 in Manhattan, where he also died. His parents, Sarah and Morris, were Jewish immigrants from the Soviet Union who settled on the Lower East Side, a poor, outsider Jewish neighborhood. It was the era of the Great Depression, shortly before the Nazis rose to power in Germany. Economic hardship helped make table tennis popular: the game required only space, a table with a net and a paddle. Reisman’s father was a taxi driver who worked endless hours and built a fleet of 17 cabs, but at night, instead of resting, he gambled. Every night. “I once saw my father lose six taxis in one night of poker,” Reisman wrote in his 1974 autobiography, The Money Player.

At age 9, Reisman suffered a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized at Bellevue Hospital. There, he learned to play table tennis and discovered that the sport was his meditation and his cure. After he was released, following years in which his father’s gambling swung the family between hunger and brief feasts, his mother threw his father out of the house. By age 13, Reisman had already won the New York junior championship, and a year later, he moved in with his father at a hotel in Manhattan.

Suckers never die

Reisman began frequenting the Lawrence nightclub and table tennis club at Broadway and 54th Street, a haunt of petty criminals, hustlers, gangsters and night people, where it was possible to make a few dollars at table games, cards or ping-pong. The club’s interior and exterior walls were scarred by bullet fragments. There, Reisman learned table tennis, the art of seduction and the craft of the con, how to dress well, smoke and attract beautiful women. He absorbed the rule that suckers never die, they are just replaced. He learned that table tennis was what he knew how to do and that it would be the wave that carried him to international fame, recognition and glory.

He sneaked into weddings at Manhattan hotels wearing a suit to eat for free, then headed to the club to scrape together money to reach real competitions.

At age 15, he arrived at the national championships in Detroit, reached the quarterfinals and went looking for his bookie to bet on his own match, as he had done in earlier rounds. Pressed for time, he saw someone who resembled the bookie and placed $500 in his hands. It turned out to be Graham Steinhoven, president of the U.S. Table Tennis Association. Two police officers grabbed Reisman and threw him out of the hall and the tournament.

At 16, after winning the U.S. junior championship, he joined a delegation of three teenagers on an exhibition tour of Britain. The war had just ended. “My father told me it was fine to be a table tennis player, but if I was only a table tennis player I would always be hungry, because there’s a limit to how many medals you can eat for dinner,” Reisman wrote. “So I had to learn to be a hustler and con naive people or become an illegal smuggler.” On the Britain tour, Reisman brought hundreds of nylon stockings wrapped in plastic and sold them at five times what he had paid.

In 1948, he traveled for the first time to the World Table Tennis Championships, an event he would attend five consecutive times, winning five bronze medals. In 1949, he won the English Open, moved to a more luxurious hotel and ran up the bill by constantly ordering alcohol through room service. When organizers threatened not to pay, he threatened not to appear at exhibition matches that had already been scheduled and publicized. They backed down.

Between 1949 and 1951, Reisman teamed up with Douglas Cartland as the opening act for the Harlem Globetrotters on tours around the world. They played music by bouncing ping-pong balls on frying pans, played on their hands and knees, staged matches with five balls, used Coke cans or chess pieces as paddles and hit the ball behind their backs, between their legs and with the soles of their shoes. On these tours, Reisman perfected his most famous trick: slicing a standing cigarette in half from the other side of the table with a ping-pong ball. Cartland was 15 years older and notoriously stingy. It was a perfect pairing, culminating in a bronze medal in men’s doubles at the 1952 world championships in Bombay.

That tournament briefly froze Reisman’s professional ascent and sent him back into hustling. The reason was the victory of Japan’s Hiroji Satoh, who defeated all opponents using a new paddle with thick rubber sponge, a technology that allowed harder hits and topspin. Reisman, a purist, argued the new paddles violated the game’s integrity. “We used to play with wooden paddles with a thin covering. The game had a soundtrack and a dialogue, and any six-year-old could tell who was attacking and who was defending,” he said. “The rubber insults my honor. It’s like prostituting a talent I was born with and shaped my entire life. Rubber turned the sport into a game. The emphasis shifted from skill to technology. Once, the ball crossed the net 30 times and matches lasted four hours. Now it barely crosses four times. All technological progress just cheats the spectators.”

In 1960, two years after winning the U.S. championship for the first time, Reisman reached the final against defending champion Bobby Gusikoff. The night before, Gusikoff beat him in a wager match. For the final, Reisman used a sponge paddle, won in straight games without breaking a sweat and swore never to touch such a paddle again.

The Reisman mythology

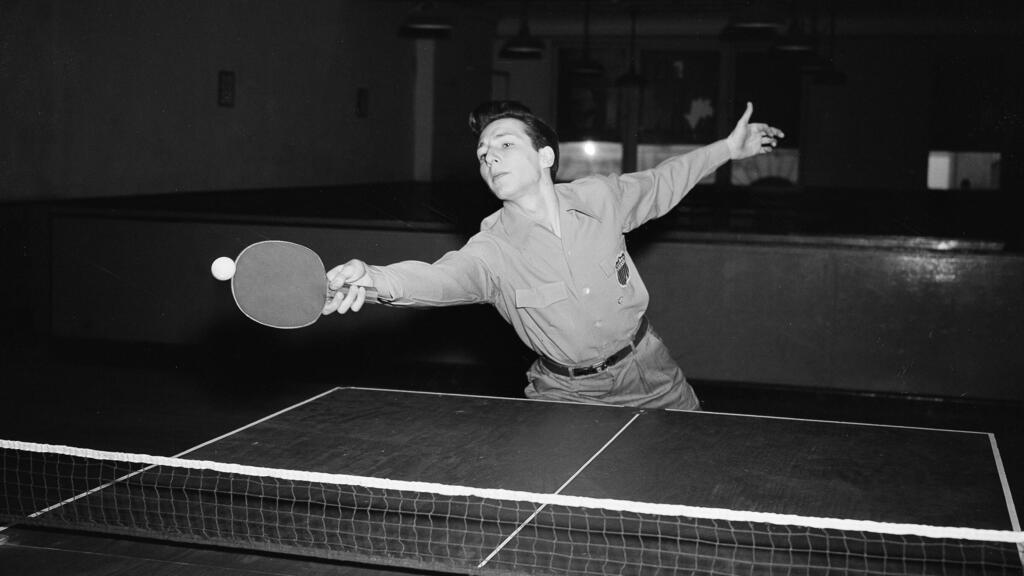

Reisman became a nomad of table tennis. He was considered one of the world’s top 10 players, but it was the blend of showmanship and phenomenal skill that made him so sought after. He was eccentric, sharp-tongued and fast-talking, earning the nickname “The Needle,” a flamboyantly dressed entertainer and philosopher of life, table tennis and above all the mythology of Reisman. The British press called him the Danny Kaye or James Bond of table tennis and claimed he had the fastest smash in the game, at 115 miles per hour.

He was invited to the palace of Egypt’s King Farouk, played against presidents and prime ministers and was advised not to take too much money from them to avoid diplomatic incidents. He defeated Satoh in a rematch in Osaka, where 55,000 people sought tickets and only 5,000 were sold. No one drew crowds to table tennis like him. The U.S. Army flew him from base to base worldwide to entertain troops. Flying on military planes exempted him from customs checks, enabling him to smuggle goods worth millions. The last time, in 1957, he entered the United States with dozens of Rolex watches strapped under his coat sleeves.

Reisman tried to settle down. In 1958, he married and two years later had his only daughter. He found a job at a shoe store and was fired after a few days because it clashed with his habit of waking up at 3 p.m. In 1960, he bought a property near Broadway and 96th Street and turned it into a table tennis club. Bankers, lawyers, market vendors and taxi drivers all came to play and drink. Bring a paddle and the courage to bet. Dustin Hoffman was a regular, as were Bobby Fischer, Walter Matthau, David Mamet and Kurt Vonnegut. Reisman was at his peak there.

He still smoked three packs a day and still competed at the world level, winning 22 championships between 1946 and 2002, but he was now almost entirely a hustler, waiting for the next sucker. He deliberately lost early games, doubled the wager and took the money.

Hustler’s paradise

If the stakes were high enough, he played sitting down. Higher still, blindfolded. He gambled playing with a lamp instead of a paddle, with a Coke can, with a book, with his glasses. There was no bet he turned down. Before matches, he measured the net with a $100 bill. “A dollar bill is about the same length,” he explained, “but it doesn’t have the same sparkle.” Creditors hired him to face people who owed them money. By his own account, Reisman was a millionaire three times and an ex-millionaire three times.

“It was a hustler’s paradise,” photographer Manny Millan recalled. “When I came to photograph him for a magazine, he immediately bet he could hit my lens with the ball. I lost and learned never to bet with him again. But I kept coming to the club. He was irresistible. People would lose to him and come back. He had style, charisma, clothes. You wanted to be around him. Players would cancel their own tournament matches or ask to reschedule them just to watch him play.”

In 1997, at age 67, Reisman won the U.S. Hardbat Championship, a tournament using only old-style paddles, becoming the oldest champion in a paddle sport. “I always needed adrenaline and risk, and if I’d been a professional and not smoked, I would have been the Superman of the game,” he once said. “But hustling and gambling were part of my DNA. Gambling sharpened my game, stripped away everything that didn’t work.

“I always wanted to be a table tennis champion. I had enough ego, ambition and passion for it. For me it was like being Einstein, Hemingway and Joe Louis in one body. But no one took my dream seriously. What I did was bet my life against everyone and against the odds. I made a career out of a game people played in basements next to the washing machine. I can’t complain.”

The film fulfills Reisman’s lifelong dream after his death: to be a pop culture icon. The boy who needed table tennis to unlock every other part of his life, who grew up poor with a father who never showed him love, and whose entertainer’s façade always concealed sadness, is finally receiving the recognition he was willing to gamble almost everything to achieve.