Everyone has a favorite Rob Reiner movie. More precisely: people who grew up as children or teenagers at the right time each have one beloved film from those eight critical years, 1984 to 1992, when Reiner seemed incapable of missing and every project hit the bull’s-eye.

The rejected and melancholy kids, those who find comfort in one close friend, still quietly tear up over "Stand by Me." Professional heartbreakers still quote "When Harry Met Sally." Rock fans swear by "This Is Spinal Tap." Stephen King devotees and self-styled tortured writers recall "Misery." Legal drama junkies devour "A Few Good Men" and Jack Nicholson’s incendiary monologue at the end. And in the end, almost everyone endlessly quotes "The Princess Bride," the fairy tale we want Grandpa to tell us before bed, but do not want to admit that we want. We are big kids - grown-ups, not babies - and we ask Grandpa for a fairy tale with a twist, with wit, with a bit of meta, and above all without too many kisses. But really, we would not object if there were one small kiss at the end.

Those were six films in eight years. Six, and each of them a gem, a Hollywood classic. Some are simply excellent ("Misery"). Most defined their genres for decades to come ("Spinal Tap" in mockumentary, "Stand by Me" in coming-of-age films, "The Princess Bride" in self-aware fantasy, "A Few Good Men" in courtroom dramas). With all due respect to "Seinfeld" — for which Reiner also bears indirect responsibility, more on that later — the New York humor built on diner situations and romantic tension between two fast-talking best friends can easily be traced back to "When Harry Met Sally."

For kids and teens who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, and a bit beyond, Reiner was Hollywood. Even if most of them did not necessarily revere his name the way they did those of contemporaries like Martin Scorsese and George Lucas. That has to do with the paths his career took after that almost inconceivable streak ended in 1992. In a word: downward. It also has to do with the fact that Reiner’s style was full of grace, yet transparent. You will not find cool archetypes, steely gazes, long lenses or cameras soaring into space on cranes. But there was a lift.

Reiner rarely wrote the screenplays for his films. Of the famous six, he wrote only "Spinal Tap," his first film. The rest were written by other screenwriters, most of them legends in their fields (Aaron Sorkin, Nora Ephron, William Goldman), who would later spend years dissecting in lectures how perfect the turning points they created were. Reiner drew the maximum from them, and his touch could be felt in something now very hard to achieve in Hollywood: respect. For the text, the scene, the actors, the audience, the story, the characters.

For Reiner, a man who grew up at the heart of the entertainment industry but never aspired to be considered a “great director,” a movie was made first and foremost for you. It was meant to tell a memorable story, one you would quote even 40 years later, moving cleanly from act to act, with an ending that would either break your heart or lift it to the skies. Hollywood at its best.

Jewish success story

But before Hollywood, there was the Bronx in New York, where Reiner was born 78 years ago. He embodied a very Jewish postwar baby boomer success story, combined with the privilege of growing up in a household of entertainment aristocracy. His father, Carl Reiner, was a legend of sharp-tongued American Jewish humor and one of the figures who helped build American television as we know it. A writing partner of young Mel Brooks and Woody Allen, and a star in his own right. Reiner Sr. won 11 Emmy Awards, but most viewers today recognize him for his small role in Ocean’s Eleven as the cranky older robber who scolds Brad Pitt and George Clooney.

Reiner’s mother, Estelle, was a legend in her own right for a certain generation, with countless projects in television, cabaret and theater. But as noted, the tragedy, or the irony, is that she will forever be remembered as the diner customer in "When Harry Met Sally" who says, “I’ll have what she’s having,” after Meg Ryan does what she does. Son Rob cast his mother in the cheekiest scene of his career because he knew exactly what perfect Jewish timing was.

Today, Rob Reiner might have been labeled early in his career a “nepo baby,” but like many successful figures of his generation, he did what it took to be remembered for himself rather than for his parents: he carved his own path. After moving to the West Coast, studying in UCLA’s legendary film department and, we are sure, plenty of hippie parties and drugs in the 1960s, Reiner slowly climbed the ladder through supporting television roles and also contributed to the industry with numerous screenplays. Steve Martin was a close friend and writing partner.

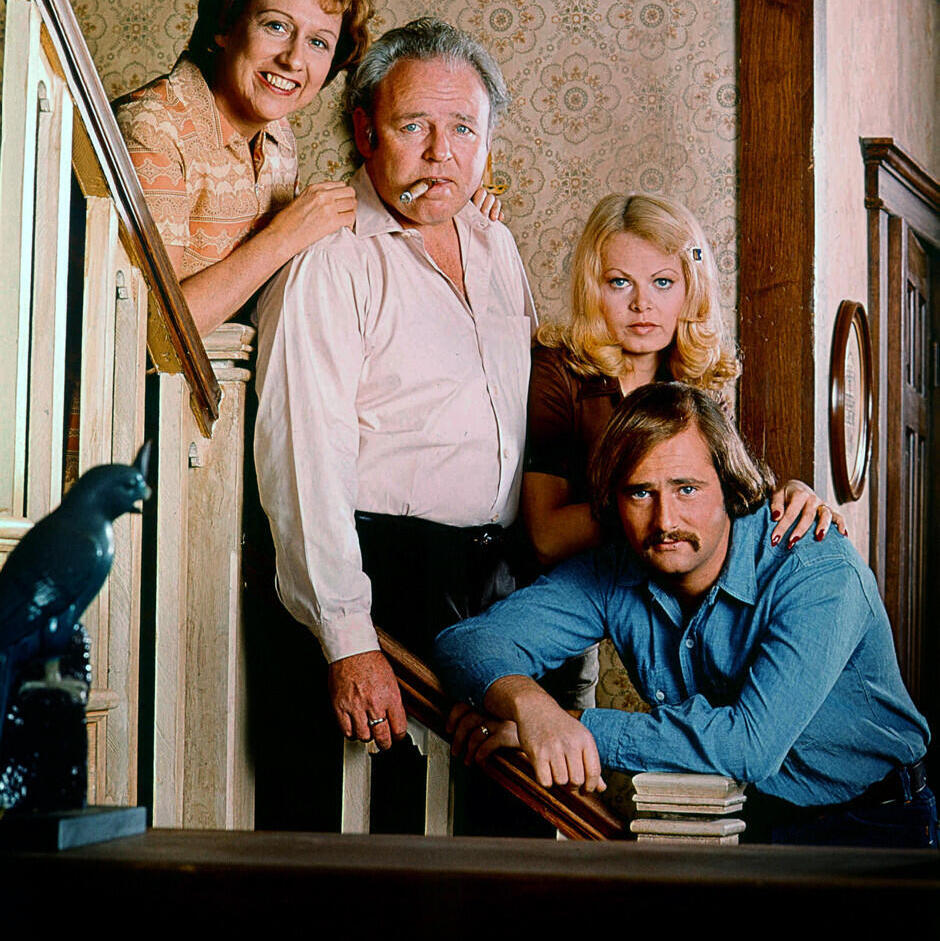

Then came the big break: his role as “Meathead.” No one predicted that "All in the Family," which ran from 1971 to 1979, would become such a cultural phenomenon that academic papers would still be written about it half a century later, with people still explaining how Archie Bunker is the basic template for a Trump supporter. By that logic, Reiner, who played the liberal son-in-law whom Bunker despised and mocked, was the first “woke” character, whom Bunker derisively called “Meathead.”

But unlike today’s stereotypes, which have become so toxic and cruel, there was no malice in that sitcom or in those characters. On the contrary, the entire series was about the push and pull between two extremes, and about the idea that in the end — in the turbulent 1970s and today — it is possible to live together. Reiner, for his part, continued to identify proudly as a liberal Democrat until his last day, endured far harsher abuse on Twitter than “Meathead” ever did and did not mind that his career flourished from a role that was partly a joke at his own expense. He was also a clear supporter of Israel and an outspoken Zionist, including a steadfast defense of Israel after October 7.

The winning streak

Back to the career: in the 1980s came a shift. Reiner came from television, a medium that was then widely looked down upon. There was no hint that he would defy expectations and make cinema that would echo for generations. It began with the uproarious "This Is Spinal Tap" in 1984, a film that at the time would have been considered experimental. After all, hardly anyone in the U.S. really knew what a “mockumentary” was. It was not as if "The Office" was airing on every corner. But the result, presenting in documentary style a band that constantly breaks up and reunites and above all fails, was simply hysterical. The rest is history.

In 1985, he made "The Sure Thing," a solid, very 1980s comedy starring John Cusack. Its biggest problem is that it is not remembered like the six other films from that period. And then came the streak we opened with.

“You can’t handle the truth!” Jack Nicholson screams at Tom Cruise in the climactic courtroom scene of "A Few Good Men." “I’m your number one fan,” Kathy Bates whispers in the adaptation of the Stephen King novel "Misery." “Train!” the boys scream as they flee across the bridge in "Stand by Me." And of course: “My name is Inigo Montoya…,” “Inconceivable!,” “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means,” and countless more from "The Princess Bride."

For any other director, the cascade of unforgettable lines and scenes Reiner delivered to audiences in the mid- to late-1980s and the very early 1990s would have secured a place in the pantheon alongside Spielbergs and Eastwoods. The legendary classical Hollywood director Howard Hawks once said: “A good movie is three great scenes and no bad ones.” By that measure, Reiner’s career was countless good movies in less than a decade, and then one big disappearance.

It is hard to think of a clearer example of a director “falling off a cliff” after such a run, even if some Reiner fans would say that description is unfair. It is not that Reiner was kidnapped and vanished into the mountains like the writer in "Misery." He kept creating, trying to stay in the game. Some films are quite charming and more important than they might seem at first glance. "The American President" from 1995, written by Sorkin, was essentially the draft for "The West Wing" (with Martin Sheen playing an adviser to President Michael Douglas, then upgrading to the role of president on television).

The writer of these lines confesses to an enormous affection for the children’s film "North," which was savaged at the time and is considered the cliff from which Reiner’s downfall began (critics, what do they know?). And some readers of these lines surely adore the syrupy "The Bucket List "from 2007, starring Jack Nicholson and Morgan Freeman joyfully dying, which was a huge hit in Israel in particular and proved that, even in old age, Reiner knew how to connect with his audience.

That may explain the rapid and surprising creative decline: his films quickly became “old.” Not in the sense of reflective and wise, but from the mid-1990s on, they were suddenly afflicted by a strange fussiness, a bit of Yiddishkeit and a lot of schmaltz.

But Reiner continued to shine elsewhere. Almost whenever he appeared as an actor, it was a delight. His role as Leonardo DiCaprio’s foul-mouthed father in "The Wolf of Wall Street" remains one of the funniest, and his turn as a grumpy New York intellectual in "Bullets Over Broadway" is no less excellent. And let us not forget that, in the late 1980s, Reiner founded the production company Castle Rock, named after the fictional town in Maine where some of Stephen King’s stories take place (including "Stand by Me"), which you may remember as “the company with the lighthouse logo.”

That company produced, among other things, "Before Sunrise," "The Shawshank Redemption" (a film Reiner was originally supposed to direct, as Hollywood’s leading King specialist at the time), "The Green Mile," "Lone Star," "Forget Paris" and a small series you may have heard of called "Seinfeld." Even if Reiner’s involvement in the show as a creator was ultimately marginal — it quickly became a monster into which NBC poured oceans of money — the fact that he was among the first to give Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David the green light for a “show about nothing” is another star in his favor.

Heartbreaking ending

Everyone has one favorite Rob Reiner movie. For the writer of these lines, there is no doubt that it is "Stand by Me." And as we bid farewell to dear Rob, who died in such a horrific way in the early morning hours in Los Angeles, let us recall the film’s ending (those who have not seen it are invited to say goodbye here).

The film’s heroes — four rejected boys who set out on an adventure to find a body in the woods — return with their tails between their legs to the town of Castle Rock. They part ways, and the narrator, the sensitive boy Gordon (Wil Wheaton), who has grown up to become a writer, casually tells us what became of each of them. Two went on to lead unremarkable lives in town, slowly becoming just more anonymous faces you pass in the hallway. The friendship faded. His best friend, Chris (River Phoenix, who would also die tragically a few years later), did not keep in touch either, but at least took his fate into his own hands. The troubled boy in the film became a successful lawyer, the writer-narrator reports. But fate caught up with him. He was stabbed to death while trying to break up a bar fight, at just over 30.

We exit the flashback. The writer looks at the final sentence he has written in his book. “I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was 12. Jesus, does anyone?” His children call him. He sets the writing aside and goes out to play with them in the yard. The song “Stand by Me” — the film’s English title — rises over the closing credits.

The hero of "Stand by Me" set aside a eulogy for a friend murdered by stabbing in order to play with his son. According to a report on the People website, the director of "Stand by Me" was stabbed to death nearly 40 years later by his own son. It is a heartbreaking, inconceivable ending that leaves a lump in the throat. It would have been worthy of the ending of one of Reiner’s films. He did not deserve such a horrific end to his life. Goodbye, Rob, and thank you for the movies.