Entire life journeys can unfold through an art form connected to plants. One such path is ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging. In this tradition, every flower, branch or leaf is chosen with great care and carries symbolic meaning.

Arrangements are created with the intention of conveying a feeling, whether of season, balance, nature or even inner emotion. The art seeks harmony between the plant material, the vessel holding it and the surrounding space. This ancient tradition is now gaining momentum in Israel as well.

Ikebana developed in Japan hundreds of years ago, initially as part of religious rituals and later as a fully fledged art form. It emphasizes simplicity, calm and balance, often using only a small number of elements. Unlike Western flower-arranging techniques, ikebana does not strive for abundance or vibrant color but for quiet restraint.

It follows clear rules for placing stems at specific angles, symbolizing the relationship between heaven, humanity and earth, and reflects the seasons, from summer flowers to autumn branches and spring buds. The process itself is considered meditative, not only how the arrangement looks at the end but how the creator feels while making it.

8 View gallery

During a workshop. Japanese see ikebana as one of the Zen arts, like martial arts

(Photo: Fiammeta Martegani)

8 View gallery

A search for balance within asymmetry, and for wholeness in imperfection

(Photo: Fiammetta Martegani)

Learning from the ‘Picasso of Japan’

One person deeply immersed in this discipline is Dr. Fiammetta Martegani, born and raised in Milan in a family of architects. “My entire childhood was spent wandering among the pavilions of Milan Design Week and the Venice Biennale. My love for art led me to study anthropology and art, specializing in the Middle East and the Far East, two great passions of mine."

Nineteen years ago, while taking a break from her studies in Sydney, Australia, Martegani was exposed to ikebana through her roommate. Back in Milan, she found a Japanese teacher, Keiko Mei, and began formal training. “Later, I decided to immigrate to Israel and start a doctorate in Israeli art at Tel Aviv University,” she says. “When I wanted to continue studying ikebana, I discovered there was no certified teacher in Israel. I contacted the Japanese Embassy, which confirmed this and suggested that I become the master of the field here myself."

Alongside her doctoral and postdoctoral studies, which led her into curatorship, Martegani began studying ikebana online at the Sogetsu School, one of Japan’s most prestigious ikebana institutions, founded by Sofu Teshigahara. He is often referred to as the ‘Picasso of Japan’ for his wide-ranging artistic talent.

Martegani explains that translating ikebana simply as ‘Japanese flower arranging’ is superficial. “That is the Western perception,” she says. “For the Japanese, ikebana is one of the Zen arts, like calligraphy, the tea ceremony and martial arts. All are considered true art forms.” As a result, ikebana works can be found in Japanese museums. She says the discipline’s principles, such as balance through asymmetry, perfection through imperfection and dynamism within strict rules, have greatly influenced her career both as a curator and as a journalist in Israel, writing for Italian newspapers.

Zen and Israeli public diplomacy during wartime

Martegani’s journalism career began almost by chance, when she filled in for an Italian colleague who was temporarily in Israel. She has been writing ever since, and especially since October 7. “There were months when I felt like I was on reserve duty, working around the clock to explain the complexity and nuances of this conflict to a world that prefers to see only black or white,” she says.

“Here too, ikebana helped me. It taught me to look at things from a different angle, just as in composition, not seeing branches and flowers as plants but as materials to connect or even sculpt."

She recalls a lesson from Teshigahara: “When you do ikebana, don't think you are arranging flowers. Imagine you are painting a painting. The flowers are your brushes, and the vase is your canvas.”

Over time, Martegani began using unconventional materials, such as recycled objects found on the street or stones from the desert. Teshigahara once said that if there were no flowers left in the world, he would use desert stones. He said this at the end of World War II, when Japan was devastated by atomic bombs and nature took years to recover in some areas. “That simple but profound sentence has helped me greatly since the war began,” she says. “It taught me resilience, a value central to both Japanese and Israeli culture."

After October 7, friends and family asked why she did not return to Italy. “That Saturday I understood this is my place,” she says. “I cannot and should not leave, especially to tell the world what is really happening here.”

Even during the darkest days, she continued to collect branches and flowers on walks with her dog in Tel Aviv, much like Japanese samurai once did. “Facing an empty vase, as I filled it gently and modestly, because less is more, I also learned to fill the vast space that had opened in my soul,” she says. “This is one of the greatest lessons I have learned during nearly 20 years on the ‘way of flowers,’ as the Japanese call the ikebana journey, a path with a beginning but no end, like all Zen philosophy."

Martegani says the greatest gift she has received from this path is the ability to teach others, through private and group workshops and collaborations with Israeli ceramic artists. This year, she is also working with the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens on both ikebana courses and the curation of Japanese art exhibitions. “In Japanese culture, aesthetics is a complete world, where the process is as important, and sometimes more important, than the final result,” she says.

“Ikebana is far more than flower arranging,” Martegani says. “It is a way to learn to see the world differently, both the magnificent microcosm of nature and the complex macrocosm of humanity.”

A fully meditative practice

Flowers also hold deep meaning in the life of Maya Baranes Pinchuk, a multidisciplinary artist, photographer and designer with more than 20 years of experience. A Shenkar graduate with honors, she says her connection to flowers began with an old dream. “They were always there, when I designed prints for fashion collections and leading brands. Working with flowers healed and calmed my soul and helped me rediscover my inner self."

8 View gallery

Maya Baranes Pinchuk. "Working with flowers healed and calmed my soul"

(Photo: Hadar Dolan)

Her attraction to ikebana stemmed from her longstanding fascination with Japanese aesthetics, encompassing everything from cuisine to kimono design. “The connection was immediate, visually, conceptually and spiritually,” she says. “Everything I value, connection to nature, uncompromising harmony, aesthetics and gratitude for beauty, comes together in ikebana.”

8 View gallery

connection to nature, harmony, aesthetics and gratitude for beauty

(Photo: Maya Baranes Pinchuk)

Baranes Pinchuk also leads practical workshops. “The goal is to pass it on,” she says. “In ikebana workshops we turn inward, honor nature and strive for minimalism.” Despite bringing abundant flowers, participants are asked to choose only a minimal number of branches, following the method’s principles. The workshops are held in carefully selected, intimate and meaningful spaces, such as the historic French Farm at Mikveh Israel.

Participants learn flower care, professional and intuitive arranging techniques, correct proportions and the basics of composition, leaving with tools to continue practicing at home. “The emphasis is on technique and therapy through aesthetics,” she says. “Ikebana is a traditional practice and a fully meditative exercise. That is where the healing comes from."

She adds that ikebana reflects the creator’s emotions and thoughts. “By letting go of what is unnecessary and focusing on the essential, we achieve inner balance and technical balance between the Kenzan (Japanese flower base) and the flowers.” Ikebana, she says, is about being present in the moment. When we are connected to ourselves and show respect for nature and time, it, in turn, supports us back. It is an endless cycle, just like in nature. Ikebana mirrors the natural life cycle: birth, growth, decline and death, and reminds us of the beauty of impermanence.

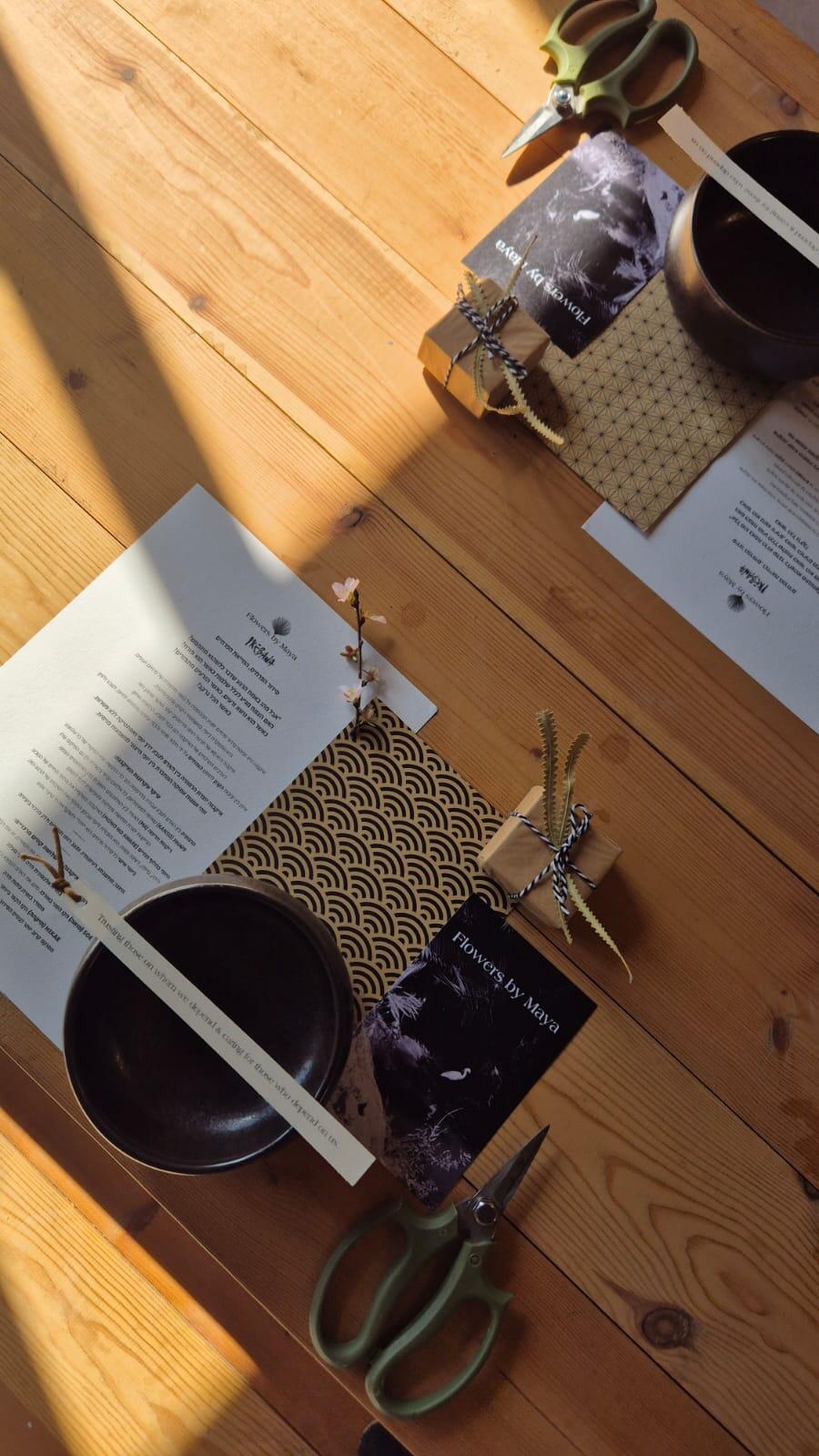

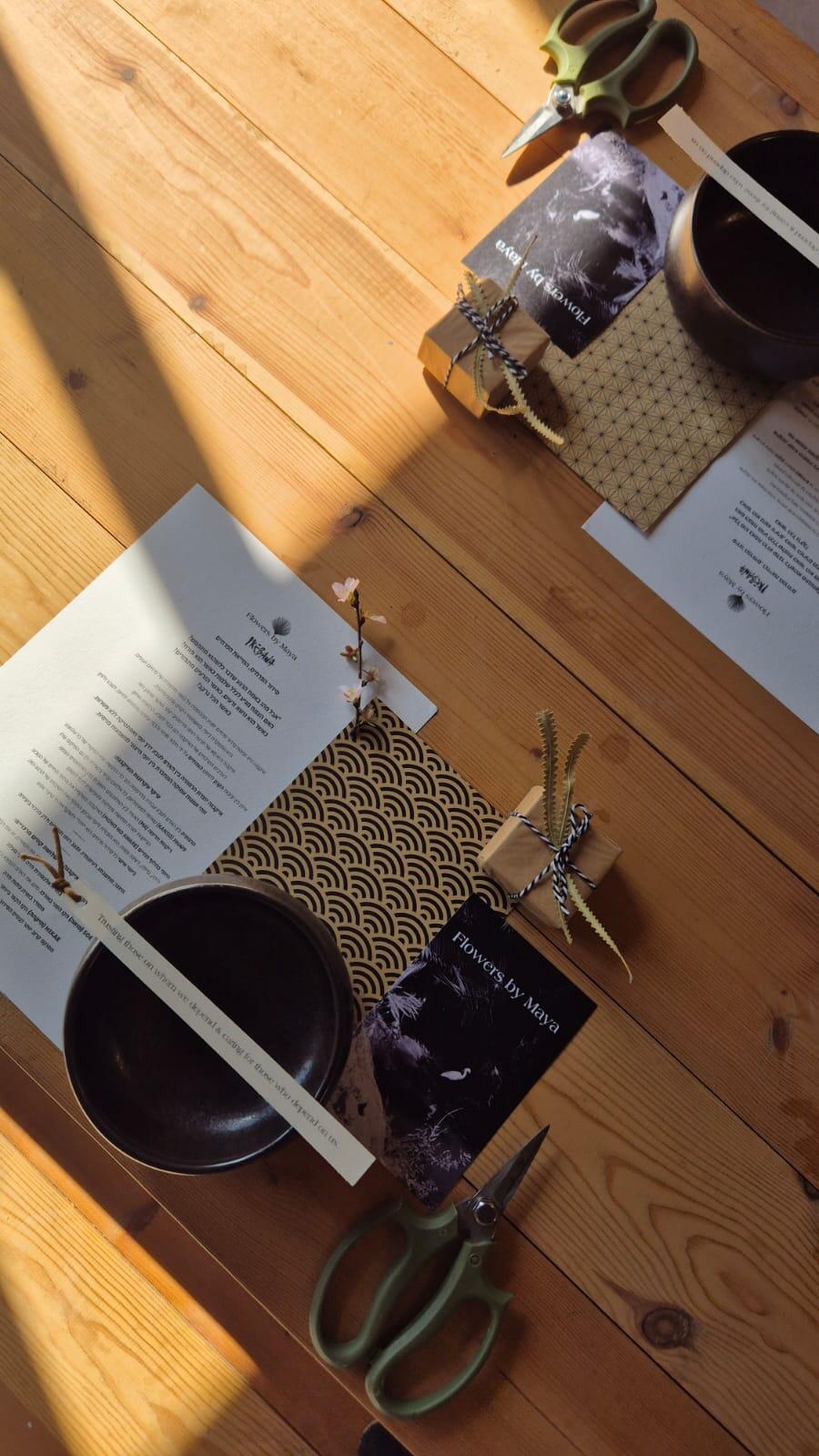

8 View gallery

The kit provided during the workshop, which participants continue to use afterward

(Photo: Maya Baranes Pinchuk)

Baranes Pinchuk's work also led her into photography, documenting arrangements as they fade. “I feared that the flowers would wither, and I found it difficult to part with them each time, because this was my art. Later on, I went on to study photography in depth.” Today she exhibits photographs of decaying floral arrangements at Gavra studio. Photography is about the fleeting moment and the longing, a concept known as Mono No Aware, which is also a key concept in ikebana, which expresses the beauty found in the transience of life. “Ikebana teaches us to cherish every moment of life, from birth to decline,” she says.

In her creations, Baranes Pinchuk explores cycles of life, seasons, fleeting light, textures and above all the free growth of flowers and branches. “They are my greatest inspiration,” she says. "Respect for nature holds a central place, and every branch, in all its forms, becomes inspiration for the next creation. With each work, I undergo a healing journey, with my state of mind expressed through the pieces rather than through words.

“Ikebana creates harmony between humanity and nature through uncompromising beauty and deep meaning. In my workshops, everyone learns the foundation and then develops their own personal expression, bringing their own truth and light into the work."