More than 40 years have passed since the assassination of Palestinian American community activist Alex Odeh, who was killed by a pipe bomb explosion at his office in the city of Santa Ana, California. The murder case remains open to this day, with no suspects and no indictments.

A new documentary titled Who Killed Alex Odeh? revisits the case and argues that it is not an unsolved mystery at all, and that U.S. authorities have long known who was responsible for the attack. According to the film, American law enforcement has been unable or unwilling to act because of political constraints, and so the filmmakers — Jason Osder and William Lafi Youmans — have effectively taken on the task themselves, conducting an alternative investigation that leads them to the suspects, who are now living among us in Israel.

The background story of Alex Odeh’s assassination draws a line between Israelis and Palestinians through the United States that is even more relevant today than it was in the 1980s, lending the film’s premiere at the Sundance Film Festival an air of tension and warning signs.

Sundance’s leadership was likely aware of the explosive subject matter against the backdrop of the current political climate in the Middle East and the United States, a context that likely contributed to the decision to invite Who Killed Alex Odeh? to compete in the U.S. Documentary Competition.

Surprisingly, despite its entanglement with contemporary events, Osder and Youmans’ polished, tightly constructed and restrained cinematic investigation avoids directly addressing the war in Gaza or Israeli policy in the West Bank. Instead, it focuses squarely on the case itself, unfolding as a classic true-crime film.

By the end, it delivers a targeted indictment of the murder suspects and those who protected them, without expanding the circle of blame or assigning collective responsibility to Israeli society for the killing of Palestinians — a temptation for many in the American public, particularly within the filmmaking community and the progressive movement, which is strongly represented at the festival.

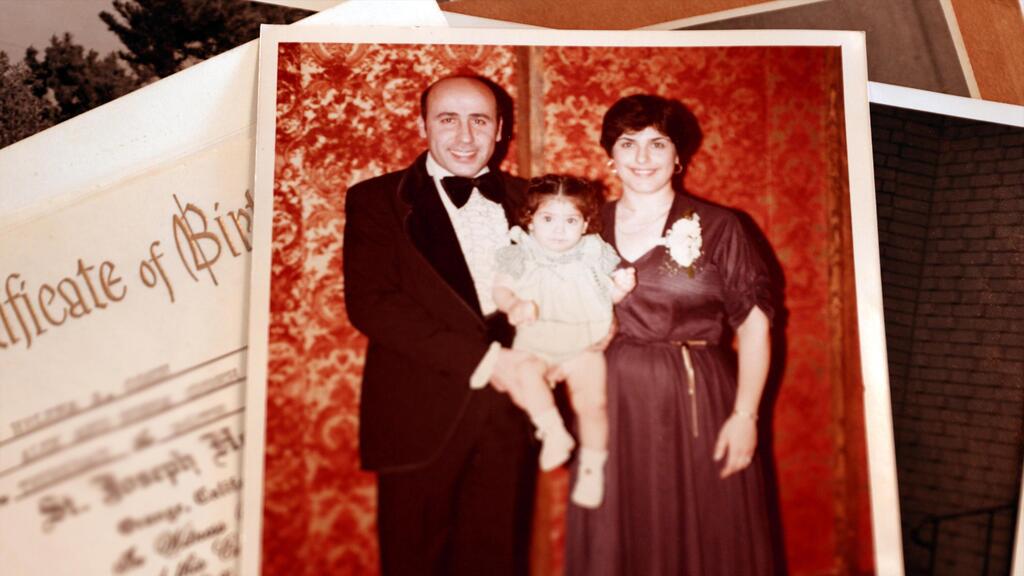

Before reaching the answer to the question Who killed Alex Odeh?, the film first asks: who was Alex Odeh? His name may not resonate with the Israeli public, but in death, he became a symbol of political violence in the United States. Odeh was born into a Palestinian Christian family in the village of Jifna near Ramallah. He went to study in Egypt, but after Israel captured the West Bank in 1967, he was barred from returning home and was forced to immigrate to the United States as a refugee. He settled in California, started a family and became a public activist as a representative of the American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee.

On October 11, just days after the hijacking of the Italian cruise ship Achille Lauro by Palestinian terrorists and the murder of the Jewish passenger Leon Klinghoffer, Odeh was killed by a pipe bomb planted behind the door of his office in Santa Ana. "He got what he deserved," Irving Rubin, head of the Jewish Defense League (JDL), declared in response.

A manhunt for the fugitives

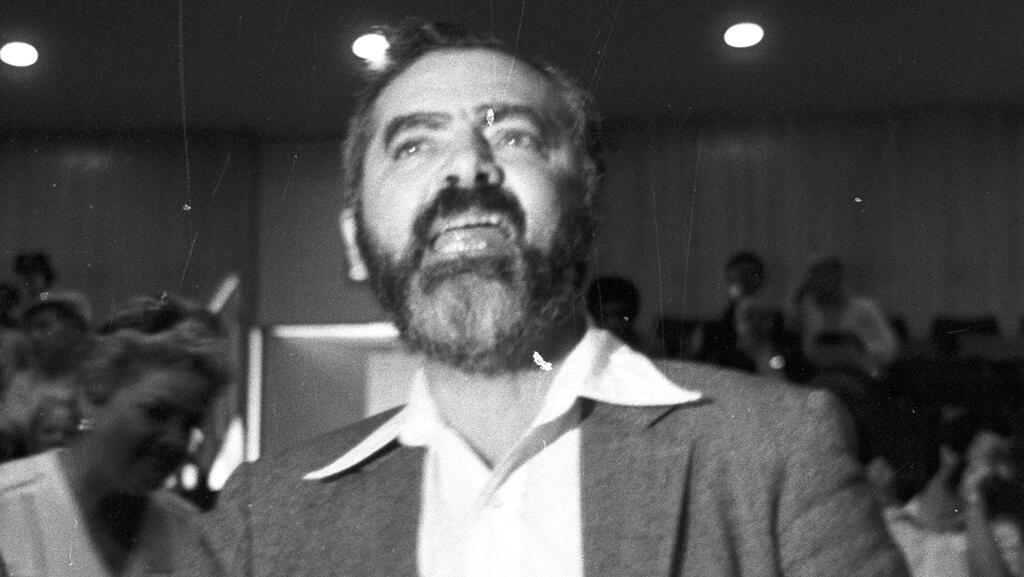

The Jewish Defense League emerged in Amerian cities as a terrorist militia deemed fully kosher by Rabbi Meir Kahane, who founded it, and decidedly not kosher by American law enforcement, which closely monitored its activities.

Kahane left for Israel in 1984 to run for the Knesset as the leader of the Kach movement, but FBI agents continued their surveillance amid concerns about escalating violence and threats against Arab organizations, including the one Odeh belonged to. The clashes intensified under Rubin’s leadership, as he continued spreading Kahane’s ideology even after Kahane was assassinated in New York on November 4, 1990, by an Egyptian-born gunman.

The confrontation between the two sides continued under the FBI’s nose, and in 1994, a memorial to Odeh in Santa Ana was vandalized. Seven years later, Rubin and his associate Earl Krugel were arrested on suspicion of plotting an attack on a Los Angeles mosque and the assassination of then-Congressman Darrell Issa.

The JDL’s aggressive and clandestine activity in the 1980s, set against the tense atmosphere following the Achille Lauro hijacking, immediately placed its members under suspicion. According to the film, three of them — Robert Manning, Keith Fox and Andy Green — were quickly identified as prime suspects by Santa Ana police and FBI investigators. All three were under federal surveillance before the murder, were in California at the time it was carried out, and flew to New York immediately afterward. Two weeks later, they were already on a plane to Israel.

Their escape effectively derailed the investigation and prevented their prosecution. All efforts to extradite them failed, including after journalist Robert Friedman publicly identified Manning, Fox and Green as suspects in Odeh’s murder in a 1990 article in the Los Angeles Times. Relying on this evidence, the filmmakers pick up where law enforcement left off, continuing the search for the three suspects under the guidance of Israeli independent journalist David Sheen.

The filmmakers first locate Manning, who was extradited from Israel in 1990 for his involvement in a separate 1980 case in which secretary Patricia Wilkerson was killed as collateral damage from a bomb intended for her employer. Three years after his extradition, Manning was sentenced to a lengthy prison term in Arizona, from which he was released under restrictive conditions in late 2023. He has never denied his membership in the JDL, but insists he never planned to harm or kill anyone.

That claim is contradicted by the testimony of Daniel Gillis, an undercover agent who infiltrated the organization and spoke with Rubin and Krugel about a plot to bomb the King Fahd Mosque in Los Angeles. According to Gillis, they expressed a willingness "to kill the children playing in the courtyard."

In his on-camera testimony, Gillis recalls that Rubin and Krugel later praised the heroism of Manning and his two partners, whom they viewed as an inspiration. Another activist serving a prison sentence adds anonymous testimony of his own, saying that in a meeting with Rubin and Andy Green, the latter was introduced to him as "the man who killed Alex Odeh."

All the evidence in the United States points to the same three men, and the filmmakers join Sheen in the search for the two remaining fugitives. Their investigation reveals that both changed their names to Hebrew ones and are living in settlements in the West Bank. According to Sheen’s reporting, Keith Fox is now publicly known as Izzy Fox. The journalist even visits him disguised as a settler and secretly records him boasting about his JDL activities and openly expressing hatred toward Arabs.

Sheen also tracks down Andy Green, who is known in Kahanist circles as "the man who killed Alex Odeh." In Israel, however, he is publicly known as attorney Baruch Ben Yosef, a resident of Kiryat Arba and a central activist in the movement advocating Jewish prayer on the Temple Mount.

In this case, Sheen keeps his distance after Ben Yosef threatens him with a defamation lawsuit. Director Osder, however, sets a trap in the form of an academic interview on "discrimination against Jews on the Temple Mount." On camera, the right-wing activist boasts of being a Kahanist, but when asked about Robert Friedman’s investigation and his alleged involvement in the Odeh case, Ben Yosef abruptly ends the interview in an attempt to escape the ambush.

The filmmakers do not obtain a self-incriminating moment of the kind seen with Robert Durst in "The Jinx," but their most compelling evidence comes from the other side of the ocean, in an interview with Hugh Mooney, who led the Santa Ana Police Department’s investigative team.

Speaking on camera, Mooney recounts that police detectives and FBI agents immediately identified Manning, Fox and Green as prime suspects, but requests for arrest warrants were denied by the Justice Department at the request of the U.S. State Department. According to the retired police officer, the Mossad was also involved in the deliberate stalling that enabled the three men to flee to Israel. Since then, all FBI requests for cooperation with Israeli authorities have been rejected, and according to Mooney, the Shin Bet itself claimed that although it had information on the suspects, it could not assist for political reasons. "The FBI was furious about it," he says.

Victims of reconciliation

Many years have passed since. Rubin committed suicide in prison in November 2002, and Krugel was beaten to death by a neo-Nazi inmate in 2005. Some have claimed they were murdered to prevent them from implicating their Kahanist associates. Conspiracy theories aside, the evidence remains in the FBI’s hands, and its representatives have assured Odeh’s widow and daughter that the case is still open and the investigation is ongoing. "If I managed to find them, how is it possible they failed?" Sheen asks in disbelief.

According to Mooney’s account, the mystery was solved long ago, but Israeli authorities have prevented the suspects from being brought to justice — despite a promise made by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during a 1998 visit to Washington, when he was asked about Odeh’s murder and pledged cooperation with the authorities.

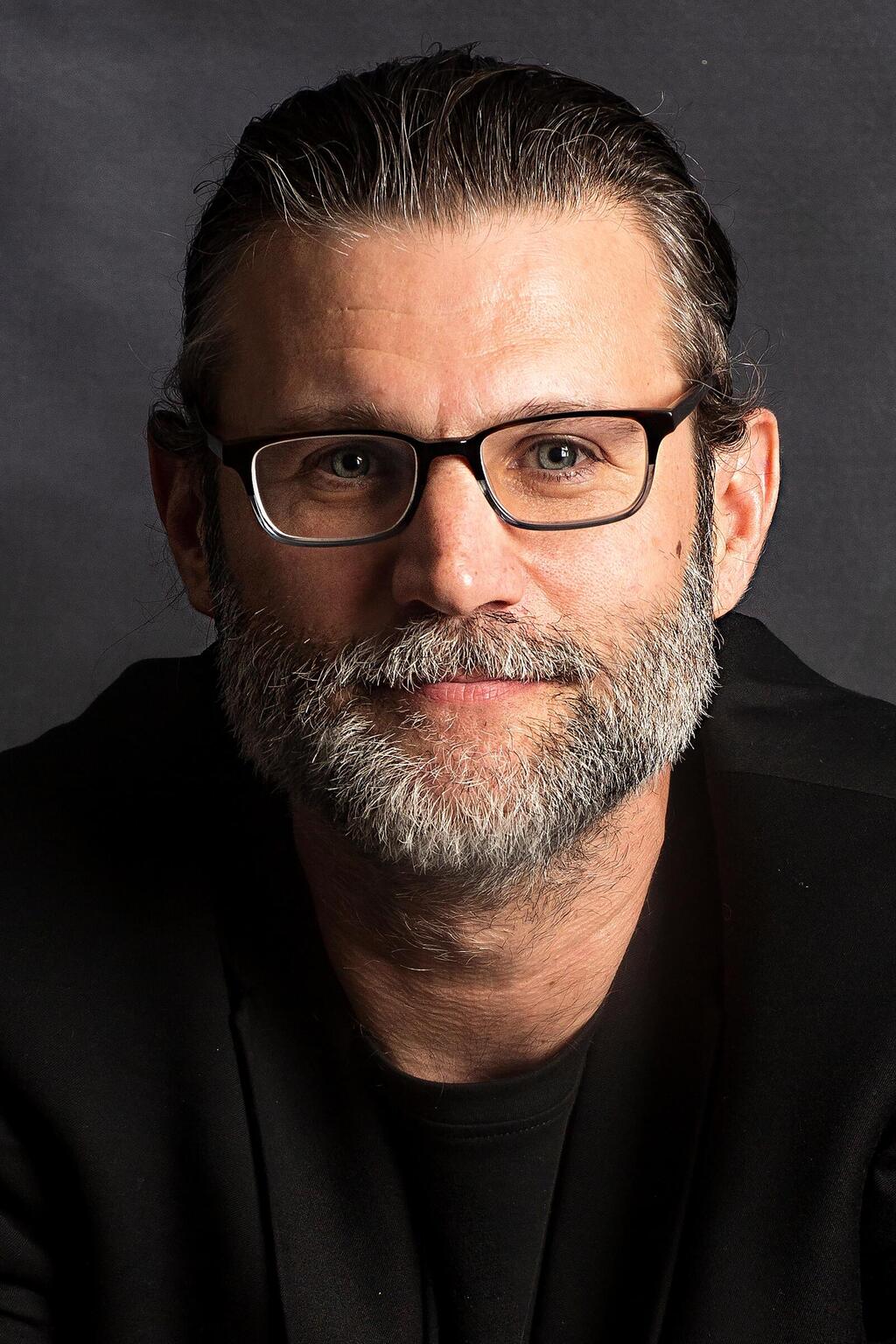

Despite the current political context, the filmmakers remain focused on the case itself and on the individuals involved. There are no explicit references to October 7 or the war in Gaza, and no accusatory finger pointed at the State of Israel as a whole. This restraint is surprising given that William Lafi Youmans is the son of a Palestinian mother and has previously described how visiting his grandparents’ home in Nazareth reshaped his view of Israel as a teenager, revealing it to him as a state that discriminates against its Arab citizens.

Since then, Youmans has followed a varied and winding path — as a rapper under the stage name "Iron Sheik," as a scholar in political science, law and communications, and as a journalist. He has written a book on Al Jazeera, taught as a professor at George Washington University and more recently at Northwestern University’s Qatar campus.

Among his other pursuits, Youmans has also engaged in pro-Palestinian activism, and some have labeled him a Hamas supporter due to social media posts opposing Israeli policy after October 7. But at least in his work as a filmmaker on Who Killed Alex Odeh?, he refrains from imposing his ideology on the film, displaying notable restraint. What Youmans and Osder do highlight is the link between the prime suspect Ben Yosef and Baruch Goldstein, and they note that National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir once interned as a lawyer in Ben Yosef’s office. Even so, they take care to distinguish these figures from Israeli society as a whole.

Kahanism is presented on screen as a danger to Palestinians and Israelis alike. The film emphasizes how extremist Jewish militias, much like their counterparts on the Muslim side, are committed to destroying any possibility of dialogue between peoples in the pursuit of peace — a vision Odeh championed and paid for with his life, like Yitzhak Rabin, who was assassinated a decade later. Both are portrayed as victims of reconciliation, their lives cut short by assassins raised and educated within the same dangerous ideological ecosystem.