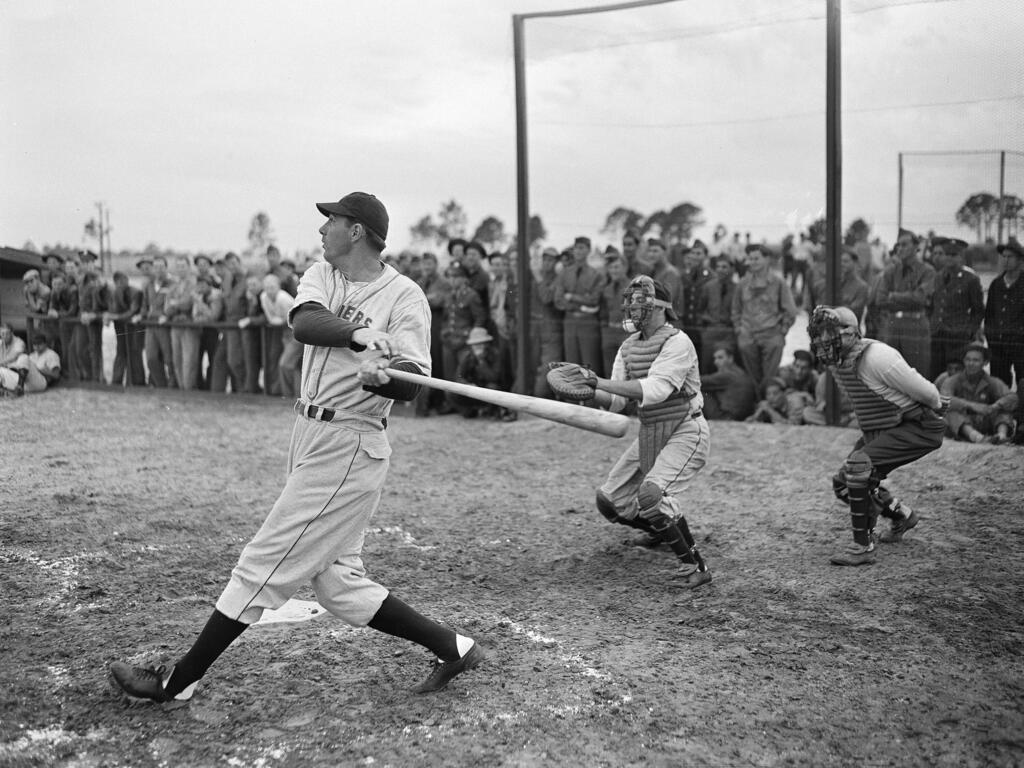

Hank Greenberg, baseball’s most celebrated Jewish star of the 20th century, combined prodigious power at the plate with unwavering courage in the face of antisemitism and wartime service, leaving a legacy that transcended the diamond.

Greenberg, who stood 6-foot-4 and hailed from an Orthodox Jewish family, struggled to find suitors early in his career. Signed and released by the New York Yankees—then anchored at first base by Lou Gehrig—and passed over by the New York Giants, he finally caught on with the Detroit Tigers in 1930. He didn’t become a regular until 1933, but went on to win two American League MVP awards, lead Detroit to four World Series appearances (winning in 1935 and 1945), and earn four All-Star selections.

In 1938, with Detroit in a tight pennant race, Greenberg refused to play on Yom Kippur, drawing harsh criticism from the press and his own team’s management. After consulting his rabbi and his father, he chose to play on Rosh Hashanah—homering twice in a key victory—and sat out the Day of Atonement. The Tigers lost that afternoon, but rebounded to capture their first World Series title in 30 years.

Greenberg was as outspoken as he was talented. During a 1930s game in Chicago, a White Sox player on the bench hurled the slur “stinking kike” at him. Greenberg confronted the visitor’s dugout, demanding the offender’s identity; no one admitted to the remark. On another occasion, an opponent asked him, “Is it true Jews have horns?”—a question that revealed the depth of prejudice he faced.

In Detroit—home to antisemitic industrialist Henry Ford—Greenberg quickly became a protector of the local Jewish community. He answered bigotry with baseball, transforming himself into a symbol of Jewish-American pride and resilience.

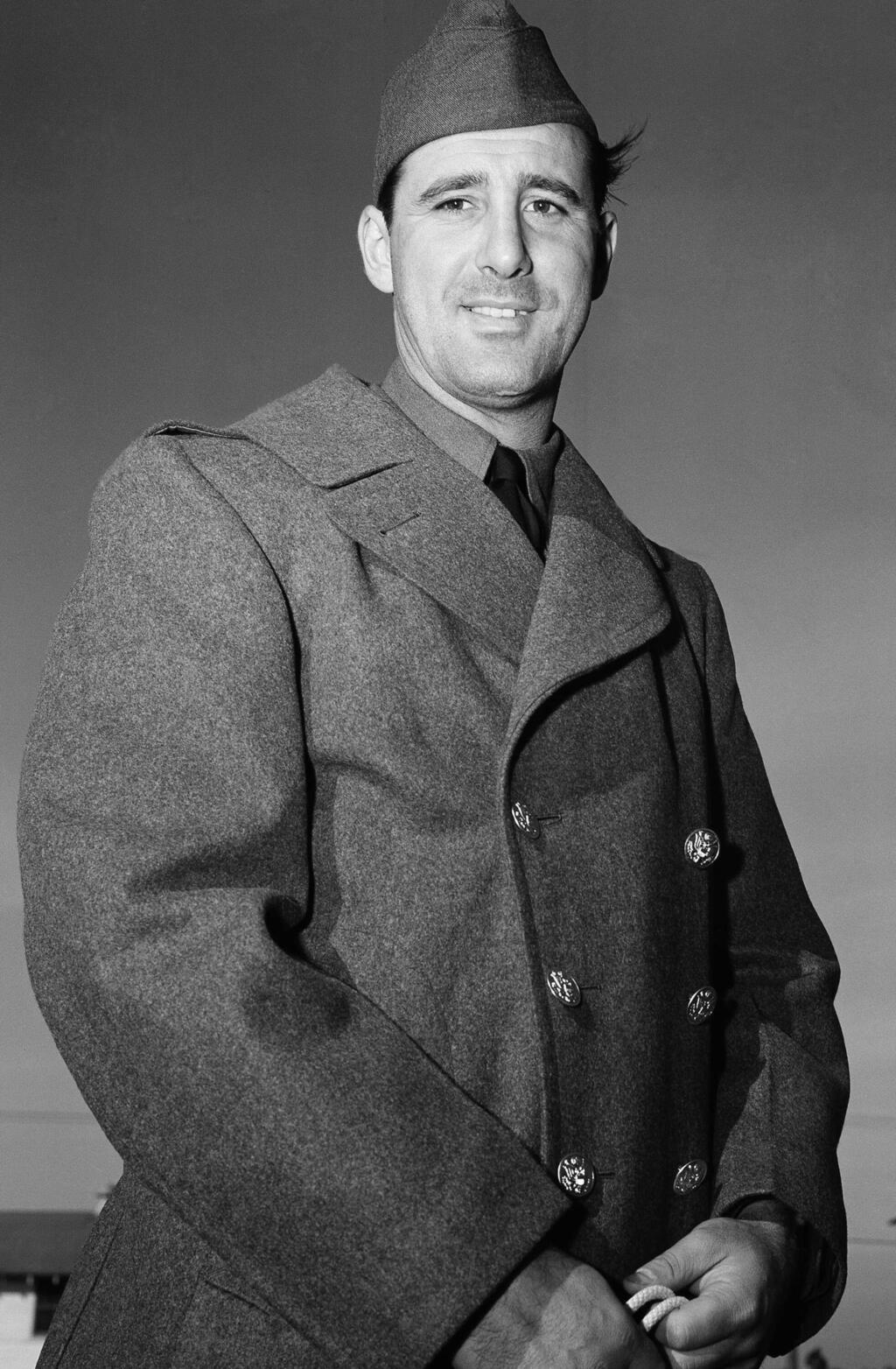

Just as he reached the peak of his career in 1941, Greenberg was drafted into the U.S. Army. Originally classified unfit due to flat feet, he insisted on a second examination and won his way into service. He was briefly discharged under a new age exemption on Dec. 5, 1941, only to re-enlist two days later after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He served nearly four years as an officer in the China-Burma-India theater, helping to identify B-29 bomber bases, and remains the longest-serving major leaguer in U.S. military history.

Rejoining Detroit in 1945 at age 34, Greenberg quickly regained form, leading the Tigers to another World Series title that fall. He later spent his final season with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1947. That same year, he was among the few major leaguers to publicly support Jackie Robinson when Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers. After a collision on the field, Greenberg checked on Robinson—an act Robinson would later praise, saying, “Class speaks for itself.”

Greenberg’s single-season total of 58 home runs in 1938 came within two of Babe Ruth’s then-record 60—a mark no right-hander would approach again until 2022.

Off the field, Greenberg married Caral Gimbel of the prominent Jewish department-store family; they had three children. Disillusioned with organized religion after World War II, he formally left the faith in 1946, though he instilled in his children a strong moral code of responsibility to humanity. He divorced in 1958 and in 1966 married actress Mary Jo Tarola; they remained together until his death in 1986.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

After retiring as a player, Greenberg built the Cleveland Indians into a 1950s powerhouse as a front-office executive. He became the first Jewish inductee into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1956. In 1983, Detroit retired his No. 5 jersey; in 1999, he was ranked 37th on MLB’s list of the 100 greatest players. The U.S. Postal Service issued a Hank Greenberg commemorative stamp, and Congress awarded him a medal for valor in military service.

Facing slurs, antisemites and the hardships of war, Hank Greenberg remained unbowed. More than a ballplayer, he was a legend in his own lifetime.

If you are interested in more information about the 1,500,000 Jews that fought the Nazis in WW2, visit the Chaim Herzog Museum of the Jewish Soldier in World War II.