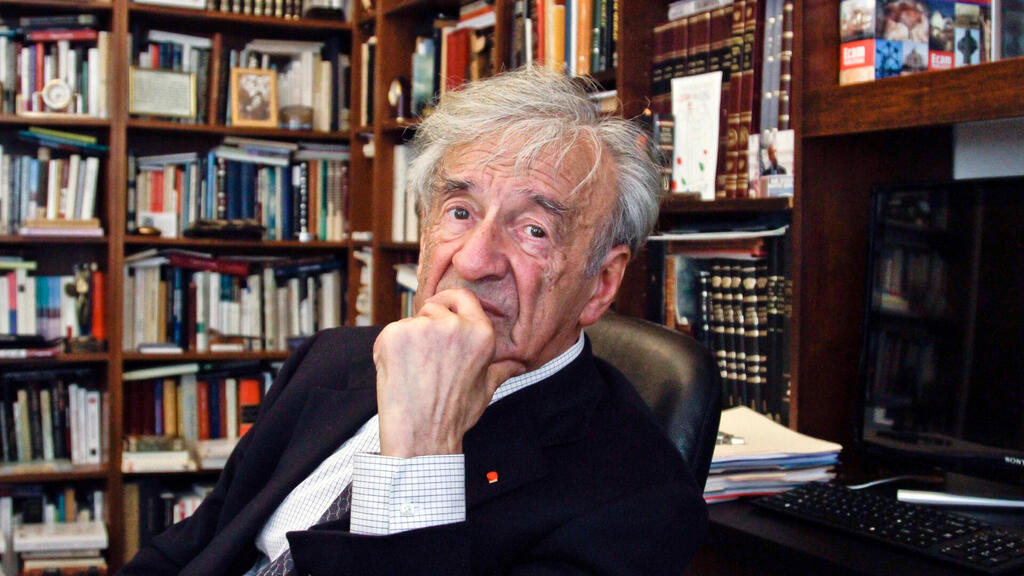

The beginning of this article dates back 18 years, during my first visit to the Boston University Library. When I began working on establishing and managing the Elie Wiesel Archive at the university, I encountered, at the entrance of the main library building, a window displaying various documents about Elie Wiesel, who served as a professor at the university.

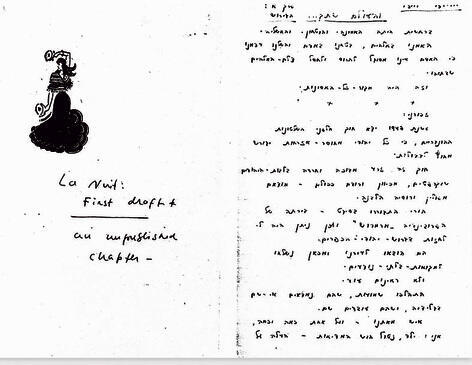

I examined the exhibits carefully, and very quickly discovered at the bottom of the window, a display that, due to being written in Hebrew, few, if any, had paid attention to – a faded page written in Hebrew handwriting. The explanation below the photographed page was "A page from the Hebrew manuscript of the book 'Night'".

Who knew until that moment that Wiesel wrote "Night" in Hebrew? An hour after I saw the small handwritten page, I asked Wiesel over the phone, where the full manuscript was? His response was, "I don't remember. In one of the archive boxes I handed over to the university. Where? I don't know".

The big surprise is the very existence of a Hebrew manuscript, even before the Hebrew translation of the book "Night" by Haim Gouri in 1963. From that moment on, the race began for me to find that unknown manuscript, about which I did not yet know when and where it was written, although Wiesel wrote in English on the document, "First draft". Two and a half years of daily work among hundreds of archive boxes were required until we reached the box containing "the prodigal son".

But that was not the end of the story. Finding the Hebrew manuscript of the book "Night" led Wiesel to say a mysterious sentence to me in a conversation, "There is another manuscript in Israel". My imagination started working because I knew from Wiesel that the large manuscript of "Night", which was written in Yiddish and printed in Argentina, does not exist, and if so, what other manuscript might be found, and furthermore, in Israel. I asked Wiesel, where in Israel? His answer was, "For several good years I moved between apartments in Paris. When 'Yedioth Ahronoth' decided to move me to New York in 1956, I looked for a place to put all the material I had collected".

Among the thousands of books dedicated to the Holocaust, a special place is reserved for Elie Wiesel's testimony book "Night", first published in Yiddish in December 1955, under the title "Un Di Velt Hot Geshvign" ("And the World Kept Silent"). "Night" has long become a canonical book on the Holocaust, one of the two most popular and researched books in the world (the other being "The Diary of Anne Frank").

It has been translated into over 40 languages and is studied in high schools and universities worldwide. Wiesel himself received global recognition with the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to him in 1986, the three highest civilian awards in the United States, as well as in various European countries, and 142 honorary doctorates awarded to him by the world's leading research universities . Alongside great admiration, "Night" and its author have also faced harsh criticism, both on the description and its credibility.

Regarding the credibility of the story, Wiesel made no compromises. To anyone who wrote to him saying they had read the "novel" he wrote, Wiesel responded with one sentence: "Night is not a novel. It is a testimony of some of the things I personally went through."

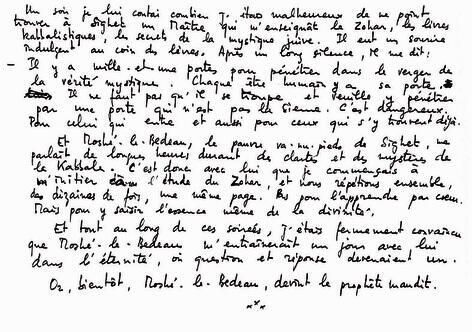

The main focus of this article is the discovery of the complete manuscript of the book in French, the first language into which the book was translated, as Wiesel lived in France at that time. The manuscript, discovered only in recent months, might alter many scholarly references in history and literature to the book.

Based on the various manuscripts of the book, I will try to trace the development of its content as it is known today, 80 years after the Holocaust, 66 years after its publication in French, and 64 years after its first publication in English. In many and varied places in his extensive writing — journalistic, mainly in the Israeli newspaper "Yedioth Ahronoth", news, publicist and literary — Wiesel addressed the process of writing the book, providing different details that need to be examined to see if they create one continuous picture.

It quickly becomes apparent that it is difficult to find coherence between the descriptions, and therefore the answer to the question, "When was the book written?" is very important. Was it written close to the liberation of the Buchenwald camp, where Wiesel was in the last period of the Holocaust? Was it written in the year or two after the liberation when he was in France — first in homes intended for Jewish boys, orphans and Holocaust survivors, and later in Paris, which began to recover from the war's damages? Or perhaps the book was written, according to Wiesel's testimony in his autobiographical book "All Rivers Run to the Sea", about ten years after the Holocaust?

Seven different versions were written of the book "Night". The first as notes from the years 1945-1947, which became the first version of the book; the second was the Hebrew version, written in my opinion in the years 1948-1950, found by me in Boston; there was also an extensive 864-page version in Yiddish that was not found, and another shortened version, from that extensive manuscript, published in 1956 in Buenos Aires.

But the most important version in my opinion is the French manuscript, found by my wife Dorit and me a few months ago in a closed storage room at the home of Wiesel's best friend, Dov Yudkowsky, who was for many years the editor-in-chief of "Yedioth Ahronoth". This version is faithful to the original and based on a complete translation of the book from Yiddish before its editing.

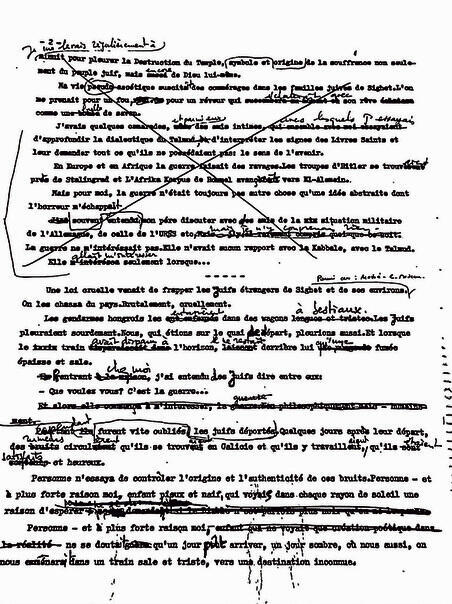

The manuscript, found after much searching, allows us a glimpse into the editing marks made by Wiesel at the request of the writer François Mauriac. It turns out that almost every page of the manuscript differs from the text we know today. This conclusion is shared by the translator Yehuda Porat, who translated several of Wiesel's books into Hebrew and looked at the discovered manuscript, as well as our family friend, Prof. Betty Rojtman, a professor of French at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The manuscript is clear evidence that Wiesel prepared a different French version for Mauriac, expecting his assistance in publishing the book. Mauriac, a devout Catholic and Nobel Prize laureate in literature, had long conversations with Wiesel, during which the young Jewish author made changes to the book, mainly removing passages that involved a confrontation between the Jewish faith of the murdered people and the religion of the murderers.

The beginning of the story is on April 11, 1945, when the Buchenwald camp was liberated. Thousands of Jews were exterminated in the ten days leading up to the camp's liberation, and thus the children's barrack number 66, where approximately 600 Jewish children and youths were found, stood out. None of them knew what the future held in store.

The Buchenwald camp was mostly destroyed by the Nazis, and today there are only a few remnants left, mainly a large building with an exhibit on what happened there during the Holocaust. The 600 children were offered a trip to France at the invitation of General de Gaulle and under the auspices of the Jewish relief organization OSE. Those who did not want to travel to France were allowed by the Americans to return to their towns and cities, and many indeed did so.

Among those who travelled to France were Wiesel, Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau former Chief Rabbi of Israel, his brother Naftali Lavie, the renowned Rabbi Menashe Klein, the educator Binam Vizhonsky, and others. In his book, Naftali Lavie writes about the days following the train's arrival with the children at a luxurious mansion in the village of Ecouis, France, where their guide Rachel Mintz awaited them. "Rachel encouraged each one individually to put on paper their experiences and memories from the war, and even organized a wall newspaper where many of us presented the first fruits of our literary creations. At least one of us continued from there the literary mission and enriched the world with his works on the Holocaust. It was Elie Wiesel who came with us from Buchenwald."

During his time in Amboise, Wiesel searched for the remnants of his family who survived the Holocaust. A publication of his photo in a Jewish-French newspaper happened to reach his older sister, Hilda, who survived the Holocaust, and with the help of the OSE organization, they met in Paris and together managed to locate another sister, Batya-Bea. From now on, his life would be full of activities.

There is no news with me. I am working like a madman, hopefully, I won't get sick. But what do I care... Have I already told you that I want to publish some books?

Among other things, he tells of intensive studies of the French language and entering the Sorbonne University, he wrote a lot. Two years and three months after he was liberated from Buchenwald, in a letter dated August 23, 1947, which he sent to his good friend David Hershkovitz, who had immigrated to Israel, he wrote: "There is no news with me. I am working like a madman, hopefully, I won't get sick. But what do I care... Have I already told you that I want to publish some books? Until now, I have already written two books and one of them will appear soon. And now I am preparing the second."

What were the two books Elie Wiesel wrote in 1947? Which of his two books was, according to him, about to be published soon? When did he manage to write? Is it possible that his testimonies, as well as those of his friends and teachers about his writing in Buchenwald and Amboise, are indeed accurate? Is it possible that he wrote his book earlier than ten years from the end of the war?

In his autobiography, he wrote that he thought about it with concern day and night; the duty to testify, to provide records for history, to serve memory... Ten years will pass before I speak. Before I submit my records. It seems the answer is clear as to the identity of the records: these are the pages of memories he began to write, according to his testimony, in Buchenwald and continued in Amboise, which would first become a manuscript in Hebrew and later the testimony book "Night."

Germans and anti-Semites tell the world that the story of six million holy Jews is just a legend and the world, the naive world, will probably believe it. If not today, then tomorrow or the day after tomorrow.

The first edition in Yiddish is concluded by Wiesel with the following sentences: "Now, ten years after Buchenwald, I see that the world has forgotten. Germany is a sovereign state. The German army is standing again like the resurrection of the dead. The irony of fate... the past is erased, forgotten. Germans and anti-Semites tell the world that the story of six million holy Jews is just a legend and the world, the naive world, will probably believe it. If not today, then tomorrow or the day after tomorrow."

In the hundreds of editions of the book in various languages published since then, the quoted passage from the Yiddish version was not included. The very important and unknown manuscript discovered this year is the original source where many changes and corrections were made, and it can be understood in the context of Mauriac's significant influence on Wiesel. Why in Yiddish is the book very anti-Christian, whereas in its known version today, this phenomenon is hardly recognized. The answer lies in the editing of the book that was translated from Yiddish to French. For example, one discussion among Holocaust researchers revolves around the question of 'revenge' at the end of World War II.

In the original Yiddish edition and the original French edition (the one recently discovered), Wiesel writes about revenge: "We are free people. The first gesture for starving people was made when we were given something to eat. People only thought about food. Not about revenge, not about parents, only about bread. Even after the hunger was satisfied, they did not think about revenge. The day after liberation, boys went to the city of Weimar to steal clothes and potatoes, and rape German girls. The historical commandment of revenge was not fulfilled."

The historical commandment of revenge was not fulfilled

However, in the version of the book sold in millions of copies, the description is different: "Our first act as free men was to throw ourselves onto the provisions. We thought only of that. Not of revenge, not of our parents, only of bread. And even when we were no longer hungry, not one of us thought of revenge. The next day, a few young men ran into Weimar to collect potatoes and clothes and to sleep with girls. No hint of revenge."

<< Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv >>

The difference between the two passages is primarily in the words 'the historical commandment of revenge was not fulfilled'. According to Wiesel's perspective in the first writing, there was an expectation of Jewish revenge against the Germans in general and the Nazi army in particular. Prof. Dina Porat, the former chief historian of Yad Vashem, discusses the difference extensively in her book 'Li Nekam Veshilem' (pages 8-27), writing that the deletion of the words "and the historical commandment of revenge was not fulfilled" resulted from the involvement of the renowned French writer François Mauriac. In her words, "The accusation against God, the God of the Jewish people alone, remained in the French version (from which the Hebrew edition), and the rest were removed, including the reference to the historical commandment of revenge".

When Prof. Porat wrote her opinion, she did not yet know that in the original French version, discovered this year, the sentence "the historical commandment of revenge was not fulfilled" exists. This is one example of many changes Wiesel made to his book at Mauriac's request, whose introductory words were crucial for Wiesel after 20 publishers (by his testimony) rejected the book. Mauriac, the devout Catholic, responded to the request of the unknown 28-year-old Jewish youth and was the key to a French publisher agreeing to publish the first book in French about the Holocaust. The revised version of "Night", according to Mauriac's requests, in French, was translated into dozens of different languages, including Iranian, Arabic, Chinese, Japanese, and many more.