Stockholm, the capital of Sweden, was wrapped in snow that evening in the winter of 1941. Karin, 7, was confined to bed, recovering from pneumonia. “Tell me a story,” she asked her mother. “What do you want to hear?” the exhausted mother asked. “Tell me a story about Pippi Longstocking,” came the answer. “Where did you hear that name?” the mother asked, and the girl said she had invented it in her imagination.

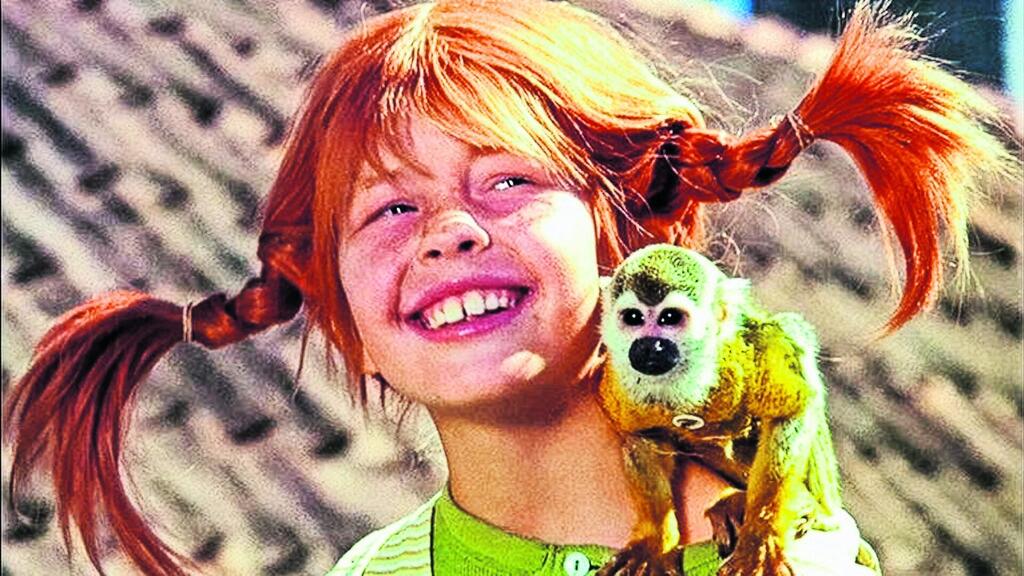

Astrid, the mother, did not ask anything more and began telling her daughter a story she made up on the spot, about a girl who, in her view, suited that strange name. Pippi in Swedish, unlike in our language, is a light, chirping kind of name, reminiscent of a birdcall. From that evening on, for two years, the mother kept telling her daughter a story about a super-girl, unbridled, free and happy, living alone with a horse and a monkey in Villa Villekulla, surrounded by a wild garden. It was a story unlike anything heard before, not in bedtime tales and not in books, and folded within it was a blunt satirical attack on the social conventions of the time.

Three years later, when Astrid herself was confined to bed because of a sprained ankle, she put the story on paper in shorthand. When she recovered, she wrote it out by hand and sent it to a literary competition held by a large local publishing house, with a note attached: “If you decide to print it, I hope it will not shock the authorities responsible for children’s education and proper upbringing.” As expected, that was exactly how the authorities and the editors felt, and they returned the manuscript to her. In the meantime, Astrid Lindgren wrote another story and submitted it to a competition announced by a small publisher called Rabén & Sjögren, winning second prize. A year later she gathered her courage and sent “Pippi” to that same house and won first prize.

The editors and owners could not resist the charm of the story, but they had cold feet about publishing it. They feared the heroine would set a bad example for children and provoke parents and educators. Lindgren was at the beginning of her career and could not object when they pruned and uprooted from the text lines that seemed too blunt or too impudent.

The book was published in 1945, with illustrations by Ingrid Vang Nyman, who created the visual prototype of Pippi. Within a short time, she became the most beloved girl among Swedish children. Swedish education authorities, along with “pedagogical” parents, initially had trouble digesting this independent, anarchic child who lived alone, did not go to school and did whatever she pleased. But they could not withstand the children’s overwhelming, unanimous vote. She was the fulfillment of their secret dreams: to live a life of freedom and independence without parents pushing them around. Pippi’s mother, as readers know, is “an angel in heaven,” and her father “heads a tribe of cannibals.” Children could fantasize freely, answer adults with cheek, waste money, skip bathing, bake and cook, and wear socks of different colors on each foot.

Even in speech, Pippi uses language anarchically. She makes mistakes, mangles and invents words, and plays tricks with language. The frequent shifts between normal talk and gleeful nonsense protest, among other things, against the tyranny of logic. In language, as in life, Pippi walks “with one foot on the road and the other on the sidewalk.”

Of all Lindgren’s future books, this first one was the most revolutionary and daring. It was quickly translated into 70 languages, including Azeri and Zulu. Pippi became the most beloved girl character for children around the world, to this day. In Russian they call her Peppi, in Germany and France Pippi. In Brazil, Bibi. In Iceland, Lina. In Hebrew, for obvious reasons, she is Bilbi or Gilgi. About 40 films and TV movies were made from the book, along with countless stage adaptations. Two sequels followed, “Pippi Goes on Board” and “Pippi in the South Seas.” The confusion the book caused worldwide is also evident in early translations, in which translators allowed themselves to change, cut and “fix” passages they considered too crude.

Feminist opinions split as well. Some argued that Lindgren harmed the female image by presenting a rough, forceful, unrefined girl. Others said Pippi embodies, more faithfully than anyone, inner female strength

Pippi is the strongest girl in the world, able to lift a horse in her arms or toss two policemen aside with ease. She is also the funniest, smartest and most truthful. She loves her freckles and her fiery red hair, is gifted with magical powers and addicted to instant gratification. She moves in a blink from reality to imagination, sweeps everyone along, refuses to grow up, and constantly mocks social ceremonies, petty-mindedness and bourgeois squareness. There is not a single moment of routine in her life, and her friends Tommy and Annika know that with her there will never be a dull moment.

There is no doubt that in creating her, Lindgren wove in elements from slapstick films, popular clowns and folk tricksters, from ideologues of open or free education (such as Alfred Adler and A.S. Neill), and from Anne of Green Gables, the heroine of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s books, which Lindgren loved most as a child.

“When I invented her,” Lindgren later said, “I only wanted to satisfy a wish that beat inside me: to meet someone who has power and does not misuse it.” That is indeed the central line of Pippi’s character. She overflows with inexhaustible amounts of goodness, honesty, friendship and care for others. She uses her power only to do good. She always stands beside the suffering, the weak and the exploited. You can always count on her to find a way out, to never tolerate dishonesty, aggression or violence. And while she scorns bourgeois values such as order and cleanliness, strict schedules, table manners, schoolwork and the like, she sets on a pedestal human values such as friendship, fairness, integrity, empathy, responsibility, imagination, creativity and humor. Against rigid discipline in child-adult relations, she offers the ideal of freedom of choice, democracy and taking responsibility.

With Pippi, a dam burst open. “If you start writing, nothing will stop you. Writing for children is so wonderful,” Lindgren said. She became Sweden’s national children’s author. She wrote about 120 books in different genres and for different ages. About a quarter of her books were translated into Hebrew. She won dozens of national and international prizes and decorations and became one of the great high priests of children’s literature. Every day she received hundreds of letters from children worldwide. In one, an Austrian girl wrote: “Does ‘Noisy Village’ really exist? Because if there really is such a village, I don’t want to live in Vienna anymore.” Each year in Sweden, two million copies of her books are replaced. Across Europe, dozens of schools and a children’s hospital were named after her. She also translated many books into Swedish from other languages. To this day, about 130 million copies of her books have been sold worldwide.

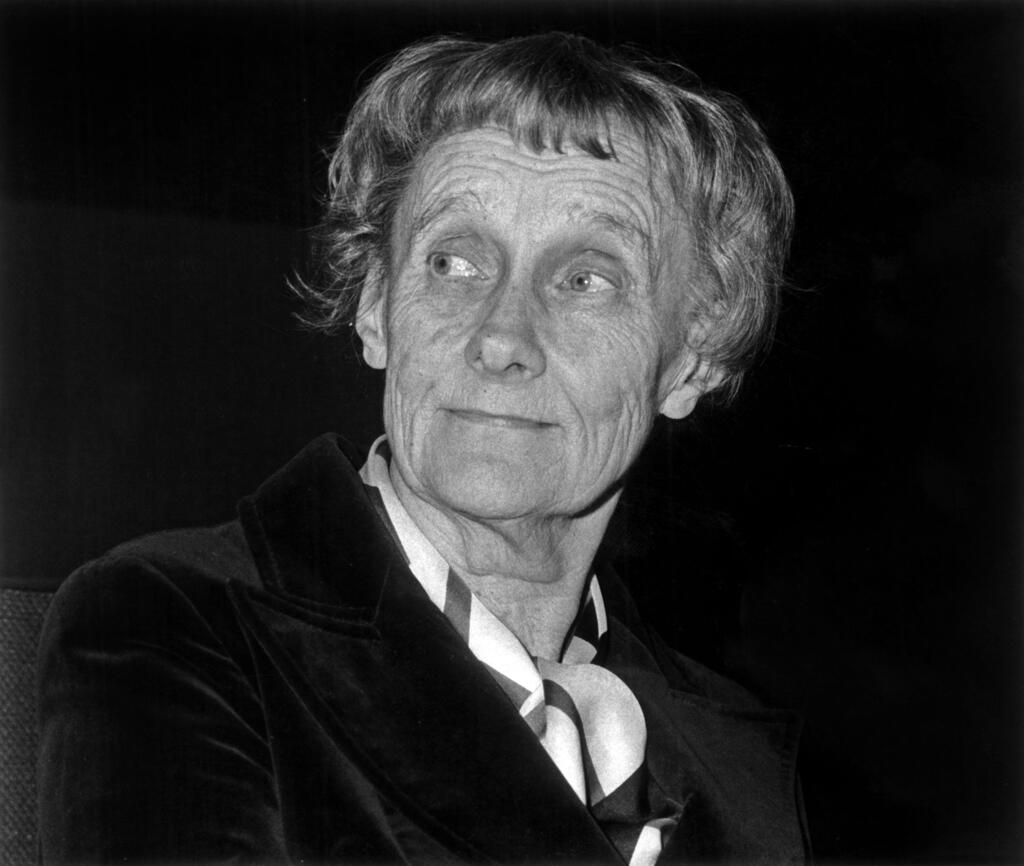

A year after Pippi was published, Lindgren was invited to become the children’s books editor at the same publishing house, a position she held until retirement, helping the company grow and flourish. Every morning she wrote at home, plays, stories, screenplays, essays. In the afternoons she worked at the publishing house on other authors’ books. “I believe deeply in children,” she said in an interview with Israeli poet and author Nurit Zarhi when Lindgren visited Israel in 1979. “I believe that human beings are better the smaller they are. When they grow up, sooner or later they become corrupted.”

Astrid Anna Emilia Ericsson was born and raised on the Näs farm, an agricultural holding leased from the church near the town of Vimmerby in the Småland region of southern Sweden. The farm stood in the heart of a beautiful green rural area whose landscapes remained in her memory as a magical childhood experience. The four Ericsson children swam in the river, climbed trees, jumped from haystacks, rode horses and helped with farm work. Their parents nurtured a thirst for freedom and independence and gave them abundant love and security.

'I believe deeply in children,' she said in an interview with Israeli poet and author Nurit Zarhi when Lindgren visited Israel in 1979. 'I believe that human beings are better the smaller they are. When they grow up, sooner or later they become corrupted.'

Since a dairymaid read her a story in the kitchen when she was 5, she fell under the spell of written words. The smell of books was, to her, “the finest perfume in the world.” She especially loved books whose heroine was a girl who coped well with her fate, like “Pollyanna,” “A Little Princess” and “Anne of Green Gables.” Before long she began spinning stories from her imagination. At 13 she published a piece in a local newspaper, after which her friends teased her and called her “the Selma Lagerlöf of Vimmerby,” after the Swedish author of “The Wonderful Adventures of Nils.” At 18 she was hired by the town paper and sank into adult books, through which she discovered that the world was not exactly a haven of happiness.

At 19 she had to leave her provincial town in haste, pregnant with a baby fathered by her married editor. She moved to Stockholm to study shorthand and secretarial work, and when her son Lars was born she placed him with a foster family in Denmark. He returned to her only about four years later, and even then he lived with her parents in Vimmerby until she married Sture Lindgren, a manager at the Royal Automobile Club, where she worked as a secretary. Three years later their daughter Karin was born.

Her 120 books were mostly episodic, many describing children’s lives in rural areas. All of her books without exception are excellent, even wonderful. “The heroes of her books,” Israeli scholar Uri Orlev wrote about her, “are children with longings who manage to fulfill their wishes, often by a kind of miracle. She places them in a chain of adventures in which imagination and reality are harmoniously interwoven. Her flowing, plastic style is saturated with playful, good-hearted humor. The events convince by their inner logic. There is no trite moral. There is zest for life, bubbling freshness and charm.”

She said children should be treated with the same respect given to adults, and she created a world in which children are respected and take their fate into their own hands. “I feel life bubbling inside me!” a line that appears often in the mouths of the child heroes of “Madicken,” could serve as a motto for all her stories. Her child characters, despite their hardships and suffering, store within them warmth, kindness, optimism and remarkable energy.

One of her most popular books is “Karlsson-on-the-Roof,” in which a boy befriends a tiny man who lives on the roof and can fly. Together they go on adventures and pranks, dress up as ghosts and drive away thieves. Of all Lindgren’s books, it was the most beloved in the countries of the former Iron Curtain, because it symbolized an escape from bondage.

'When I invented her character,’ Astrid Lindgren later recalled, ‘I only wanted to fulfill a wish that pulsed inside me: to meet someone who has power and does not misuse it.’ And indeed, that is the central thread in Pippi’s character. She is filled with inexhaustible reserves of goodness, honesty, friendship and care for others. She uses her strength only to do good

Her novel “The Brothers Lionheart” (1973) sparked a fierce debate in Sweden over mentioning death in children’s books. In it, two brothers, one sickly and physically deformed, transform their “lives” when they tumble into Nangijala, a kind of children’s paradise. But even there there is no rest. Monsters must be fought, and the two end up in a kind of double suicide, reaching another afterlife realm called Nangilima. Lindgren was sure she had written a comforting book about brotherly love that helps children face loneliness and fear of death. But the school system roared, believing the book caused death anxiety. Many children wrote to Lindgren saying that after reading it, they were no longer afraid of death.

“The Brothers Lionheart” is one of her three great dramatic novellas, along with “Mio, My Son” and “Ronia, the Robber’s Daughter.” They revolve around our big existential fears: the need to be loved and valued, fear of loneliness and worthlessness, love of life and fear of death. The last is a kind of Romeo and Juliet, but with young lovers who are children of robber gangs from rival clans.

Alongside her writing, Lindgren was a social activist. A special law was passed in Sweden at her insistence to protect animals from suffering on the way to slaughter. She fought fiercely against beating children. She also fought, and defeated, Sweden’s crushing income tax rates. She belonged to an organization that helped Jews escape Nazi Germany, and she wrote against the Vietnam War. In her final years, almost blind and hard of hearing, she stopped meeting readers in clubs and schools, but children in Sweden and around the world continued to make pilgrimages to her.

Astrid Lindgren lived a long life. She died in January 2002 at her home in Stockholm at age 94, surrounded by her daughter, her sister, seven grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren. With her death, a singular figure left the world, the last of the giants of children’s literature.