In an exclusive interview, Sam Sussman opens up about experiencing antisemitism as a teenager, his mother’s long-running romance with the legendary musician, and the shattering revelation she shared just before dying of cancer: “As a kid, people often told me I looked like him. I could never let go of that suspicion."

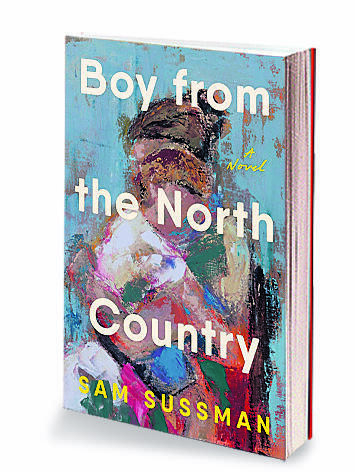

Sam Sussman’s debut novel, "Boy from the North Country", an autobiographical work about life under the suspicion that his real father is Bob Dylan, was published just weeks ago and has already stirred up a storm.

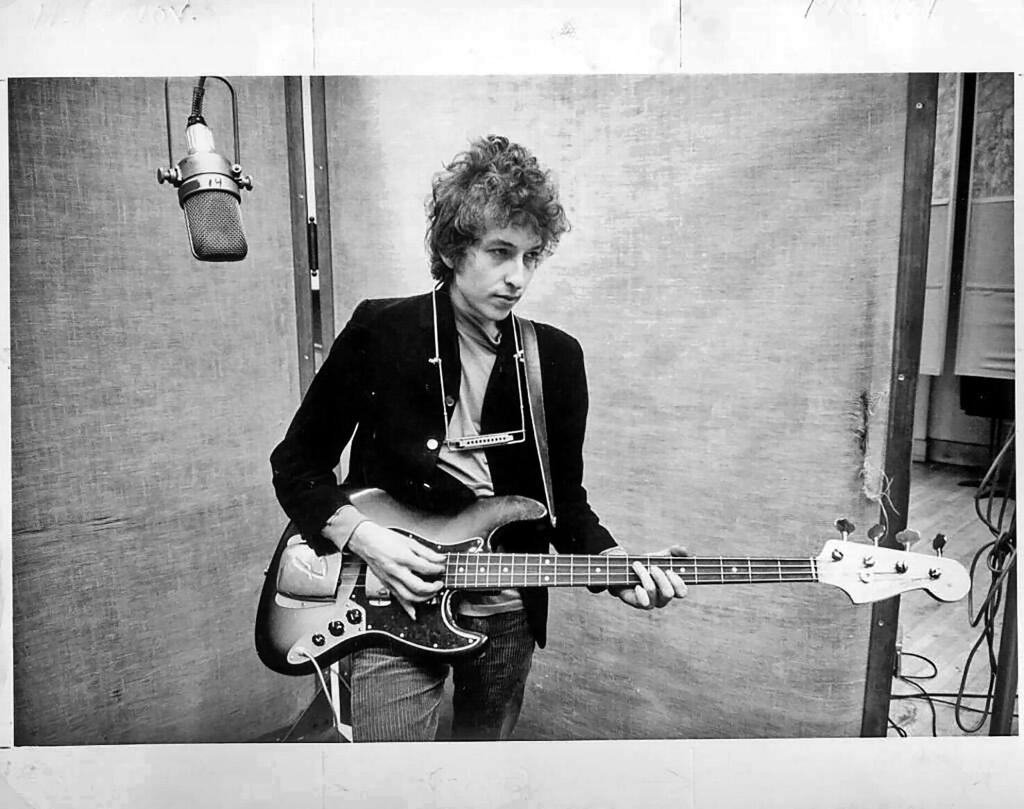

The book has rocked New York’s tightly knit literary scene, earning Sussman a profile in the New York Times Sunday Magazine, complete with a photo spread mimicking some of Dylan’s most iconic portraits. There have been reviews in major newspapers, buzzed-about events at top cultural institutions, and a U.S. book tour that’s landed Sussman on multiple bestseller lists.

Despite the attention, Sussman hasn’t let success go to his head. A dear friend and former fellow at LABA (a Laboratory for Jewish Culture that uses classic Jewish texts to inspire the creation of art, located on New York’s Lower East Side), where I teach, Sussman remains grounded and charmingly modest.

Behind his golden Jewfro, a hairstyle uncannily reminiscent of his possible father’s iconic curls, and a winning smile, articulate wit, and intellectual depth, he’s still the sensitive, tormented young man readers meet in the novel.

Behind the sparkle in his eyes, there’s a flicker of sadness, a kind of orphanhood that no amount of fame or recognition is likely to heal.

Last week, between readings and flights, we caught up over a glass of bourbon. I had a few questions, and Sussman answered them with his trademark honesty and directness.

Still, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn, consciously or not, he was holding something back, and that the story he’s telling the world is just the tip of a deeper, more painful iceberg that may never fully surface.

The novel’s plot, explicitly autobiographical, unfolds in Goshen, New York, located in the once-rural town in the southern Catskills.

The biblical name “Goshen” belies the town’s grim present. Once a picturesque region of forests, farmland, and quaint farmhouses, Goshen was hollowed out by rapid industrialization and, later, economic decline. In Sussman’s telling, it's a place marked by poverty, despair, ignorance, violence, and widespread addiction to opioids and other hard drugs.

In recent years, Hasidic communities have begun moving into the area, forming insular enclaves that often clash with the broader population.

The narrator’s mother, an eccentric, bohemian figure, moved to Goshen before Sussman was born. Clues scattered throughout the novel suggest she was fleeing the chaos of her wild urban life.

As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that much remains unsaid. Sussman himself, it seems, sometimes escapes into the pastoral illusion of the very place he couldn’t wait to leave.

Today, every story is expected to be "special", but yours is truly extraordinary. Tell us about yourself.

"I was raised by a single mother who left Manhattan before I was born and moved to a remote rural town called Goshen, in upstate New York. My childhood was both beautiful and terrifying. At home, I lived in a bubble of love, beauty, art, and poetry. But outside, I experienced violence and hatred daily, and I felt that the adults in my life couldn’t protect me.

"As a kid and teenager, people often told me I looked just like 'that singer... Bob Dylan!' But my mother avoided talking about him, until I reached an age when I could back her into a corner, and she finally admitted she had a years-long affair with Dylan before I was born.

"She said there’s a chance he’s my biological father. That knowledge has haunted me throughout my adult life. I left Goshen the moment I could, wandered through different universities and cities across the globe, had many adventures, but I could never shake that suspicion.

"A few years ago, I published an autobiographical essay in Harper’s called The Silent Type, which was the first time I told this story. Now, it appears in fuller form in my novel Boy from the North Country."

What was it like growing up as the only Jewish kid in a wild, deeply antisemitic rural part of New York?

"As a kid and teenager, I endured horrifying antisemitism, which I describe in the novel. We lived not far from Kiryas Joel, a closed community of Satmar Hasidim embedded in the conservative, rural heart of the southern Catskills of New York.

"It’s a stronghold of Trump supporters. The antisemitism—the burning hatred toward the Hasidic neighbors and all Jews—was normalized and constant.

"My classmates at the public school I attended were raised to believe that Jews were thieves destroying their town. At school, I faced open antisemitism daily. Boys would throw coins at me in the hallway, because, as everyone 'knows,' Jews are obsessed with money. Sometimes they pinned me down and tried to force-feed me bacon.

"It was a brutal, violent environment. When our school bus passed Kiryas Joel, the other kids would shove my face against the window, point at the bearded men in Hasidic garb, and ask, ‘Which one of those Jew guys is your dad?’ My mother begged the school to intervene, to protect me from the abuse, but their answer was always the same: ‘That’s just how boys are.’

"Eventually, I realized no one was going to protect me. I had to learn to protect myself. I started going to the gym every day after school. I trained obsessively, built muscle, and one day I beat up one of the boys who’d been harassing me.

"After that, I never experienced physical violence again. But nothing could change the sense that I didn’t belong in the world I grew up in. I had a few rare and treasured friends, but mostly I found refuge in books and writing."

Your novel reads like a love letter to your late mother. She’s portrayed as a beautiful, wise, creative, and sensitive woman. Tell us about her and your relationship.

"My mother was extraordinary. She followed her heart, often into places far from the ordinary paths taken by women of her generation.

"In her twenties, she left Long Island, moved to New York City, and studied acting with some of the best teachers of the time. But when it came to raising me, she chose to live deep in the woods of the Hudson Valley, near the town of Goshen in the Catskills.

"She loved nature, animals, and the life of a free-spirited artist. Our yard was full of chickens and dogs, and we even had a gray mare named Cloudy. I still have a photo of us riding her together, I was three years old. One of my earliest memories is of her reading to me from a book.

"She worked as a holistic therapist, practicing meditation, yoga, and healthy nutrition. She was an old soul, the kind of person you scarcely meet. She radiated warmth and calm, and she had a way of listening that made people confide in her, sharing their most intimate secrets.

"After she died, exactly eight years before the novel was published, I felt I had to create a space where I could hold on to her memory and wisdom. "Boy from the North Country" is where I buried my mother."

The novel portrays your relationship as idyllic. Was it really that simple and smooth, or were there shadows and sharp edges?

"Simple? Not at all. The entire novel is built around the tension between us, especially her refusal to talk about the things that really mattered.

"At one point, the son says to his mother, cruelly, that the reason she never found true love is because she doesn’t deserve it.

"In my novel, the love between mother and son isn’t automatic; it’s something hard-won, earned over many years. So no, nothing was simple or easy in our relationship. Not in real life, and not on the page."

"I never tried to contact him. As far as I’m concerned, his role in my life is over"

Let’s talk about the heavy shadow looming over your novel: the absent father, who may be Bob Dylan. What role does Dylan play in your life?

“My mother had a long relationship with Bob Dylan, but she hardly ever spoke to me about it."

“When I was 15, I pushed my mother and made her confirm that she and Dylan had been together during the year before I was born. That was as far as she would go.

"Looking back, I think she was trying to protect me from the very shadow you’re asking about; she feared my biography would be covered by his very public one.

"I left home in my late teens and spent my twenties moving between cities around the world, trying to find my own voice and become a writer. Did I live in Dylan’s shadow during those years? Good question. I’d like to think not, but who knows?

"When I was 25, I was studying at Oxford, and my mother was diagnosed with uterine cancer. I returned to Goshen to be with her during her final days. In those intense, intimate moments, I realized that everything I am, everything that makes me who I am, comes from her, not from him. She’s the one who raised me, loved me, and shaped me.

"Today, I’m far less obsessed with the question of Dylan’s paternity. It no longer feels relevant. My novel is a story about a boy searching for a lost father, and finding his mother instead.

Indulge me for a moment: Are you willing to share the real, non-literary story? Did you ever have any actual contact with Dylan? Did you try to reach out? Were you worried he’d react strongly to the novel?

“When I published the full story as an essay in Harper’s a few years ago, before I even started writing "Boy from the North Country", I got a letter, unsurprisingly, from Dylan’s legal team. They demanded to see the draft before publication and asked for a photo of my late mother. After reviewing everything, their response was: ‘No comment.’

"I haven’t heard a word from them since, and I don’t expect to. For my part, I never tried to contact him. As far as I’m concerned, his role in my life is over.”

Regardless of whether Dylan is your biological father, are you a fan of his music and writing? Have any of his songs influenced you over the years?

“Yes, of course. I deeply respect him as an artist. What other popular musician had the nerve to turn the biblical story of the Binding of Isaac into a rock hit?"

Your novel has just been released and already it’s receiving a lot of buzz, widespread attention, and, if I may say so, commercial success. Did you expect this? What were your thoughts while working on the book and offering it to agents and publishers?

“I’ll answer with a quote from the book. In one scene, the character based on my mother learns a lesson from the legendary acting teacher Stella Adler, descendant of Yiddish theater royalty and a pioneer whose method shaped actors like Marlon Brando and Robert De Niro.

"In the scene, Adler tells her that an actress must never care whether she’s admired or ignored. The only thing that matters is the need to embody the character in full.

"That’s the spirit I tried to carry through the process of writing this book. I sat at my desk for years, writing and deleting, time and again. Success was the last thing on my mind. As Samuel Beckett said: "Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better."

“On days when writing is hard, I read Amos Oz”

As mentioned earlier, your upbringing, as you describe it in the novel, is very different from the stereotypical Jewish-American childhood we know from books and movies. Still, those who know you understand that despite being secular, you feel a deep connection to your Jewish identity, both as a person and as a writer. Can you tell us more?

“You’re right. I didn’t grow up in any Jewish community, and I’m not religious, but I still feel deeply Jewish. To me, the power of Judaism lies in the fusion of spiritual and artistic life.

"Jewish culture survives through storytelling. From the Bible to Leonard Cohen’s lyrics, Jewish wisdom is passed from generation to generation through narrative. That’s sacred to me.

"More than once, I’ve started my writing day by reading the Psalm I chose as the epigraph to my novel:

"It is a good thing to give thanks unto the LORD, and to sing praises unto Thy name, O Most High; To declare Thy loving kindness in the morning, and Thy faithfulness in the night seasons, With an instrument of ten strings, and with the psaltery; with a solemn sound upon the harp. For Thou, LORD, hast made me glad through Thy work; I will exult in the works of Thy hands." (Psalms 92).

"As you pointed out, I didn’t have a typical Jewish childhood, not even close. But looking back, I now see that Judaism was present everywhere, even if it seemed far from our daily lives.

"My mother created a kind of private shtetl for us, all our own. She devoted her life to healing, to tikkun, to divinity and love, and she drew her inspiration from studying Kabbalah. Think about it, we lived in Goshen.

"To me, this is the secret of Judaism’s strength: it survives in the hearts of people even when life takes place far from any conventional Jewish community or lifestyle.”

We both know that Hebrew and Israeli literature currently occupy a diminished place in the American publishing world. And yet, you frequently reference it and treat it with respect, which is rare for an American writer of your generation. How did you come to Hebrew literature, and how has it influenced you?

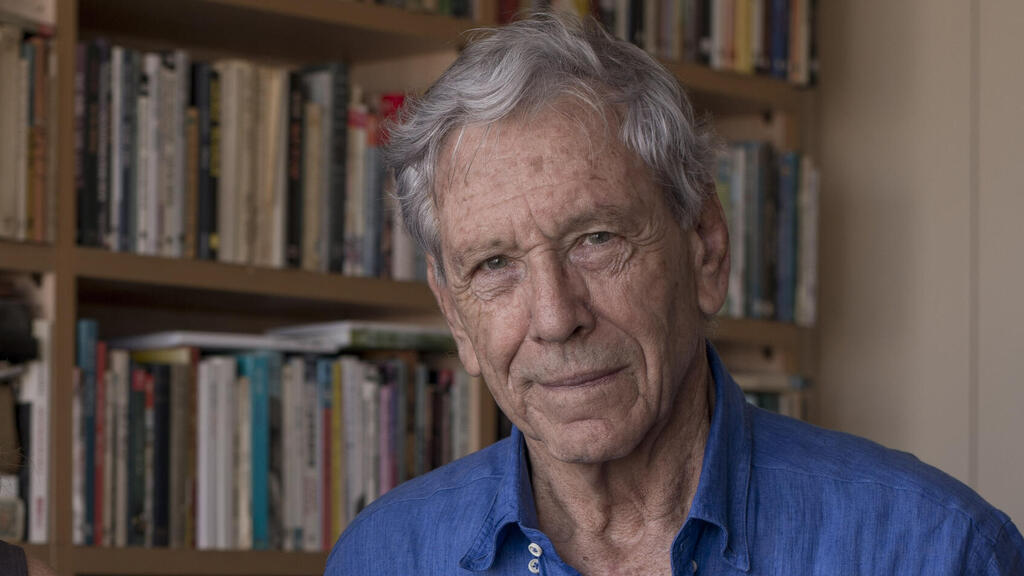

“Hebrew literature has had a profound impact on me. On days when I find it hard to write, I’d call one of my closest friends and we’ll read a chapter aloud from "A Tale of Love and Darkness" by Amos Oz.

"In my view, it’s the greatest modern story of a mother and son. It moved me so deeply that I gave my protagonist the last name Klausner, as a tribute to Oz.

"The first book I re-read after finishing the first draft of my novel was "To the End of the Land" by David Grossman. For some reason, I felt the need to be immersed again in his sorrow, his grief, his silence.

"From you, Rubi, I’ve tried to learn how to weave Jewish history and theology into modern prose. I read "The Ruined House" over and over, long before we ever met. You know that, right?”

First published: 17:26, 11.01.25