Scientists have identified what they say is the world’s oldest securely dated cave art, a hand stencil created at least 67,800 years ago on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, reshaping understanding of when and where human symbolic culture emerged.

The discovery comes from limestone caves in southeastern Sulawesi, part of the Indonesian archipelago, which researchers say hosts some of the earliest known rock art anywhere in the world. The findings were published in the journal Nature.

“When we think of the world’s oldest art, Europe usually comes to mind, with famous cave paintings in France and Spain often seen as evidence this was the birthplace of symbolic human culture,” the researchers said. “But new evidence from Indonesia dramatically reshapes this picture.”

The research team, made up of Australian and Indonesian scientists, documented and dated rock art motifs from 44 cave sites in southeastern Sulawesi, including 14 previously unknown locations. Using advanced laser-ablation uranium-series dating, they analyzed microscopic calcium carbonate deposits that formed on top of the paintings, allowing them to determine minimum ages for the underlying images.

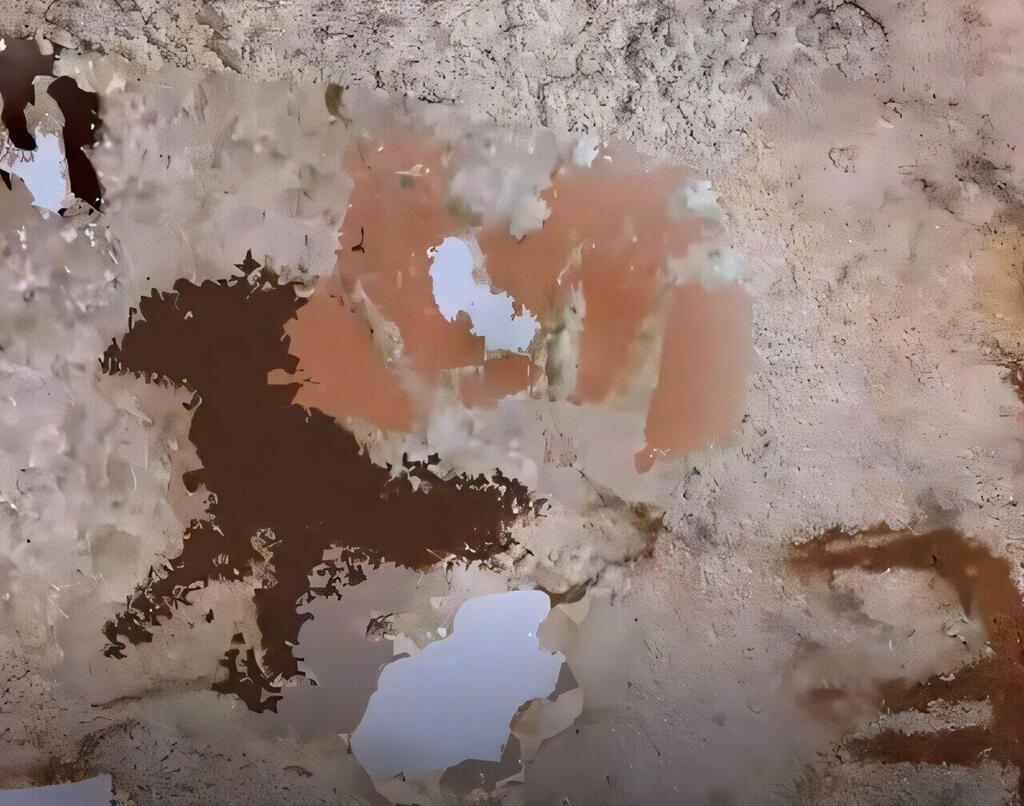

At one site, Liang Metanduno on Muna Island, a calcite layer covering a faint red hand stencil produced a uranium-series date of 71,600 years, with a margin of error of 3,800 years. This establishes a minimum age of 67,800 years for the artwork, making it the oldest demonstrated cave art ever found.

The Sulawesi hand stencil is more than 16,000 years older than the earliest dated rock art from southwestern Sulawesi and slightly older than a hand stencil in Spain previously attributed to Neanderthals, which until now held the oldest minimum age for cave art worldwide.

“These artists were not only among the world’s first image-makers, they were also likely part of the population that would eventually give rise to the ancestors of Indigenous Australians and Papuans,” the researchers said.

The hand stencil is notable not only for its age but also for its unusual form. The tips of the fingers appear to have been deliberately narrowed, creating a pointed, claw-like shape — a style so far identified only in Sulawesi.

“Altering images of human hands in this manner may have had a symbolic meaning, possibly connected to this ancient society’s understanding of human-animal relations,” the researchers said.

Earlier work in Sulawesi has identified cave images of figures with both human and animal features, including bird-like heads, dated to at least 48,000 years ago. Together, the findings suggest that people in this region held complex symbolic ideas about identity and the relationship between humans and animals deep in prehistory.

The dating results also show that cave painting in southeastern Sulawesi was not a one-time event. Art was produced repeatedly over tens of thousands of years, continuing through the Late Pleistocene and into the Last Glacial Maximum around 20,000 years ago. After a long gap, the caves were painted again by Austronesian-speaking farming communities who arrived about 4,000 years ago, adding new images over much older Ice Age art.

“This long sequence shows that symbolic expression was not a brief or isolated innovation,” the researchers said. “Instead, it was a durable cultural tradition maintained by generations of people living in Wallacea.”

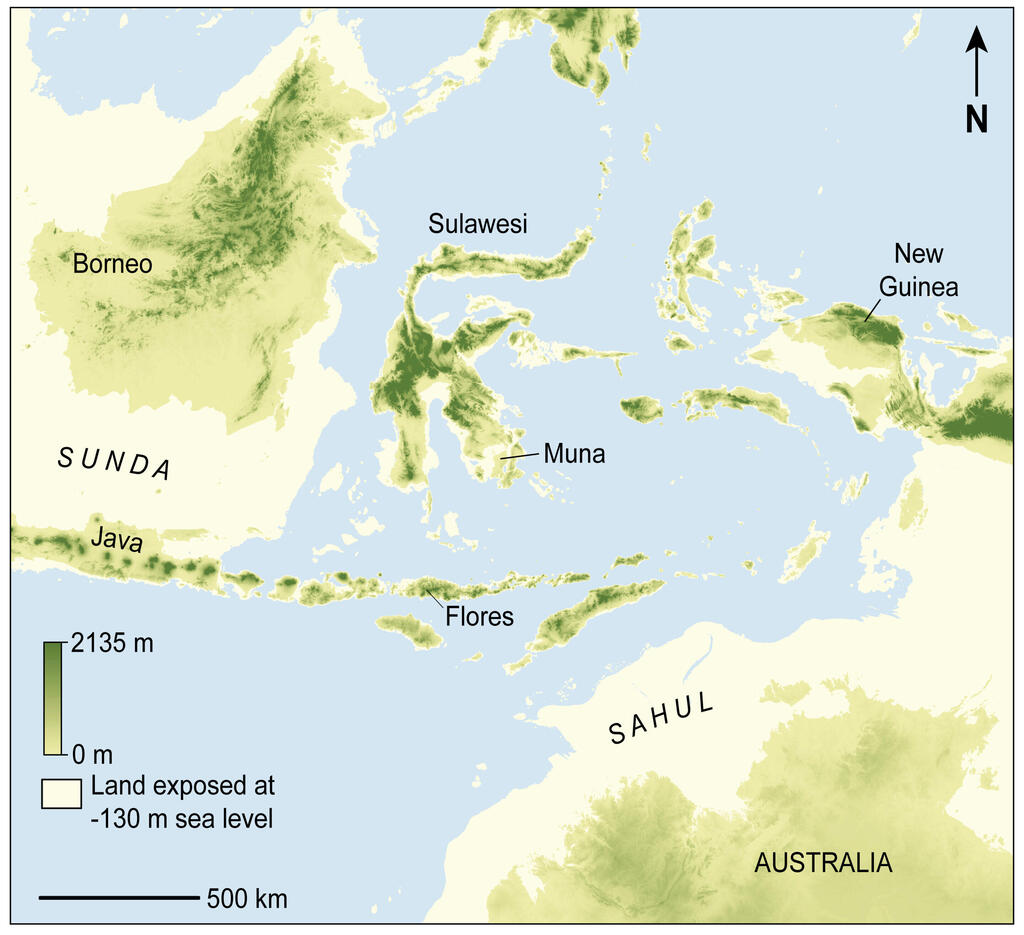

The findings have major implications for understanding early human migration. Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests modern humans reached Sahul — the ancient landmass that once connected Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea — between about 65,000 and 60,000 years ago, a journey that required deliberate long-distance sea crossings.

Researchers have proposed two main migration routes into Sahul: a northern route through Sulawesi and onward to New Guinea, and a southern route through islands such as Timor toward northern Australia. Until now, there has been little archaeological evidence along these pathways.

The newly dated Sulawesi rock art lies directly along the northern route, providing the oldest known archaeological evidence for modern humans in this key migration corridor, the researchers said.

“In other words, the people who made these hand stencils were very likely part of the population that later crossed the sea and became the ancestors of Indigenous Australians,” they said.

The discovery adds to growing evidence that early human creativity did not arise in a single place or remain confined to Ice Age Europe. Instead, symbolic behavior such as art, storytelling and the marking of identity was already well established in Southeast Asia as humans spread across the world.

Large areas of Indonesia and neighboring islands remain archaeologically unexplored, raising the possibility that even older examples of human art and culture may still await discovery.

“The story of human creativity is far older, richer and more geographically diverse than we once imagined,” the researchers said.