A new Israeli study shows that listening to the sounds fish make while eating can enable real-time monitoring, early detection of disease and more precise feeding in aquaculture ponds.

The research will be presented on Tuesday at the International Sea The Future 2026 conference in Eilat, hosted by the Agriculture and Food Security Ministry and the Negev, Galilee and National Resilience Ministry. Listen:

The sounds produced by fish can reveal whether they are hungry or sick

Contrary to the common perception of the underwater world as silent, it is in fact rich with sound. Marine environments are filled with communication signals between animals, noises created by movement and even sounds accompanying everyday activities such as eating.

The study, conducted in the laboratory of Dr. Shay Tal at the National Center for Mariculture at the Eilat branch of the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute, reveals how these ‘sounds of the sea’ can be harnessed for advanced aquaculture monitoring. The research was carried out in collaboration with Dr. Shai Kendler, Prof. Barak Fishbain and Dror Ettlinger-Levy, PhD Student of Technion.

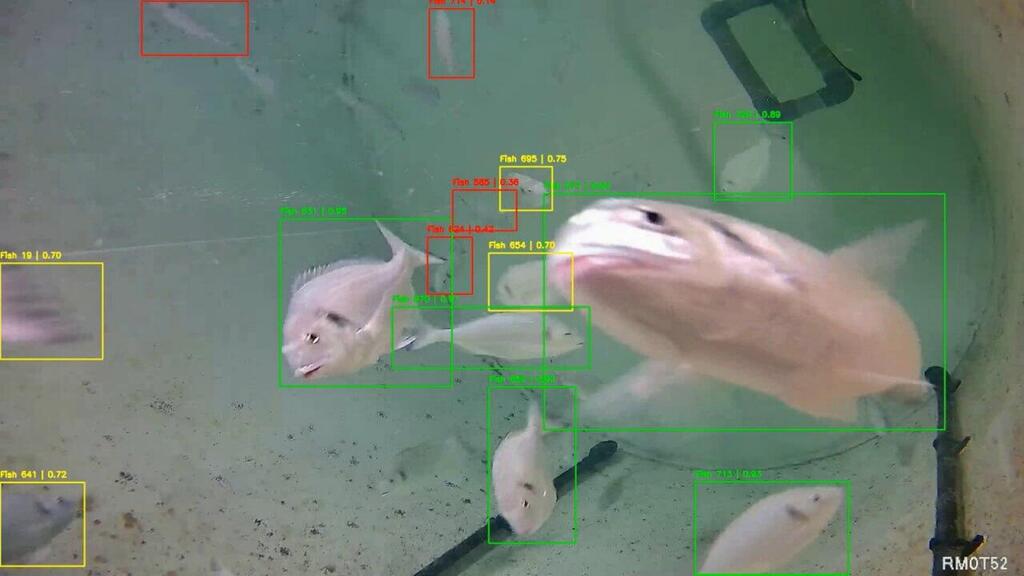

The researchers identified distinct sounds produced by fish while feeding and used an artificial intelligence model to determine whether the fish were hungry, satiated or under stress.

Today, feeding quantities in fish farms are typically calculated based on estimated fish weight and general feeding tables. This is a rough assessment that does not account for changing conditions such as illness, stress or environmental factors. Sound, the researchers found, can fill that gap.

In experiments conducted on gilthead seabream, the team identified for the first time the specific sound fish make when biting food pellets. Using advanced signal processing methods, they were able to isolate the biting sound from background noise in the fish farm.

The practical implication is that fish farmers can feed the fish, listen to their response and then decide whether to continue or stop feeding.

Monitoring feeding behavior is a critical tool for fish growers, Dr. Tal said. “Overfeeding harms the environment. Excess food sinks and pollutes the water and also increases production costs. On the other hand, underfeeding slows growth, causes stress and raises the fish’s vulnerability to disease,” he said.

The sound-based approach has also been applied in a separate project involving shrimp, where researchers identified sounds linked to courtship and aggression, enabling real-time monitoring of behavior.

Preliminary results from a similar study on shellfish will also be presented at the conference. In that research, scientists identified the sound of shell closure, providing insights into stress levels and environmental impacts.

“The integration of research and development, aquaculture and advanced technologies allows Israel to lead innovative solutions to food supply challenges driven by climate change and population growth,” said Yuval Lipkin, head of the Food Security Administration at the Agriculture Ministry.