A mass grave linked to the Justinianic Plague, the earliest documented pandemic in the Mediterranean region, has been discovered in the ancient city of Jerash in Jordan. The findings provide rare and direct evidence of how the deadly outbreak affected urban populations between the sixth and eighth centuries CE. The Justinianic Plague occurred from 541 to 544 CE and was the first in a series of plague outbreaks that continued until about 750 CE.

Archaeological excavations found that hundreds of people were buried rapidly over the course of just a few days in an abandoned civic space, laid directly atop layers of pottery shards. This burial pattern differs sharply from modern cemeteries, which expand gradually over time, and points to a sudden mortality crisis consistent with plague conditions.

5 View gallery

The Roman Forum in Jerash set against the modern city

(Photo: Ciro Fanigliulo/Shutterstock)

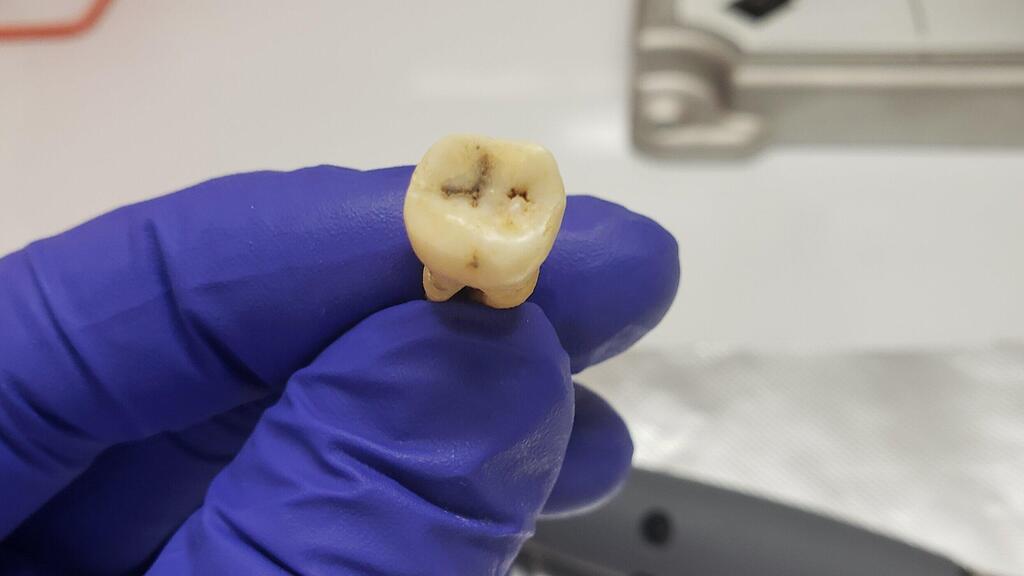

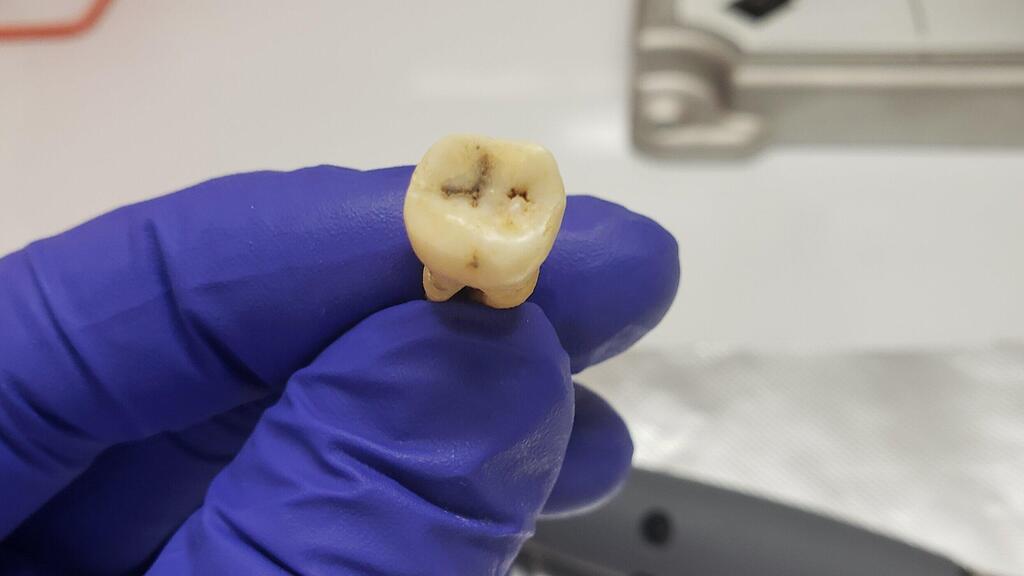

5 View gallery

A tooth discovered at the archaeological site in Jerash

(Photo: Greg O'Corry-Crowe, Florida Atlantic University)

The study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, combines bioarchaeology, ancient DNA analysis and archaeological context. Its findings confirm the presence of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for bubonic plague. As a result, Jerash is the first site where a plague-related mass burial has been confirmed both genetically and archaeologically, resolving long-standing debates that had previously relied only on historical texts.

The research team, led by Dr. Rays Jiang of the Department of Global, Environmental and Genomic Health at the University of South Florida, has now completed the third study in a series examining the plague outbreak also known as the Black Death.

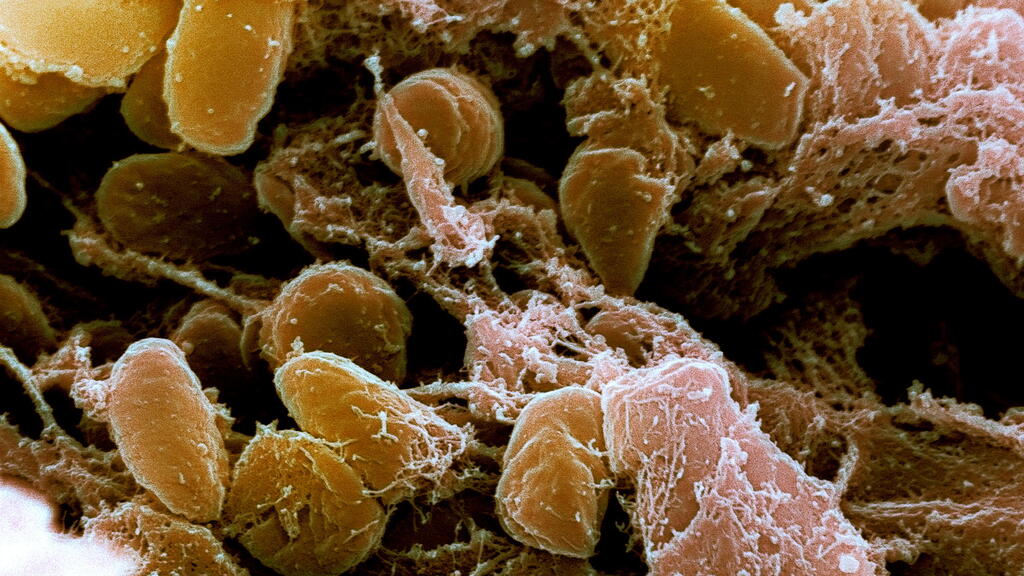

5 View gallery

A mass grave site from the earliest documented plague in the Mediterranean region

(Photo: Karen Hendrix, University of Sydney)

Jerash, located in northern Jordan, contains the remains of a Hellenistic-Roman city that was once a major center of the Byzantine Empire. The findings from the mass grave uncovered there add to the historical record of what caused the deadly outbreak that killed millions of people. “We wanted to move beyond identifying the pathogen that caused the plague and focus on the people it affected — who they were, how they lived and what death from plague looked like within a real city,” Jiang said.

During the Justinianic Plague, those affected lived in diverse and often unrelated communities. In death, however, the plague brought them together, as many bodies were buried side by side, as recently uncovered. Jerash is the first site where a mass burial linked to the deadly plague has been confirmed both archaeologically and genetically. “The site at Jerash turns this genetic signal into a human story about who died and how the city experienced crisis,” Jiang added.

The findings provide direct evidence of large-scale human mortality, along with insights into how people moved, lived and became vulnerable within ancient cities. While most of the burials suggest that individuals grew up where they were interred, trade, migration and the rise of empires also brought people together across the Middle East.

The evidence indicates that those buried in Jerash were part of a mobile population that lived within the broader urban community of ancient Jordan, united by the crisis of the time and ultimately buried together in the mass grave. “By linking biological evidence from the bodies to the archaeological environment, we can see how disease affected people within their social and environmental context,” Jiang said. “This helps us understand historical pandemics beyond the textual record.”

The findings are reshaping understanding of the Justinianic Plague by demonstrating not only widespread mortality but also how urban density, mobility and social vulnerability shaped its impact. The site at Jerash offers a powerful reminder that pandemics are not only biological events but also profound social crises, with patterns that continue to resonate in the modern world.