The United States is currently enduring an exceptionally severe, widespread and prolonged cold wave. For more than a week, hundreds of millions of Americans have faced temperatures plunging to minus 30 degrees Celsius, along with heavy snow, hail and ice. Dozens have died as a result of the ongoing winter storm, hundreds of thousands have lost power, and thousands of flights have been canceled. The damage is estimated at more than $100 billion, and another storm reached the country over the weekend.

Such a prolonged cold spell has not been seen in the United States for decades. President Donald Trump questioned on his social media platform how such extreme cold aligns with claims that the global climate is warming. This is not the first time he has expressed skepticism about the climate crisis. Recently, the United States withdrew from several major international organizations focused on climate change and environmental protection.

Heavy snow in the US

(Video: Reuters)

Global climate versus local weather

First and foremost, global warming refers to the climate of the entire planet, not to weather at a specific place and time. The weather varies from region to region, day to day, night to day and season to season. Climate change, by contrast, is measured as a long-term global average over many years.

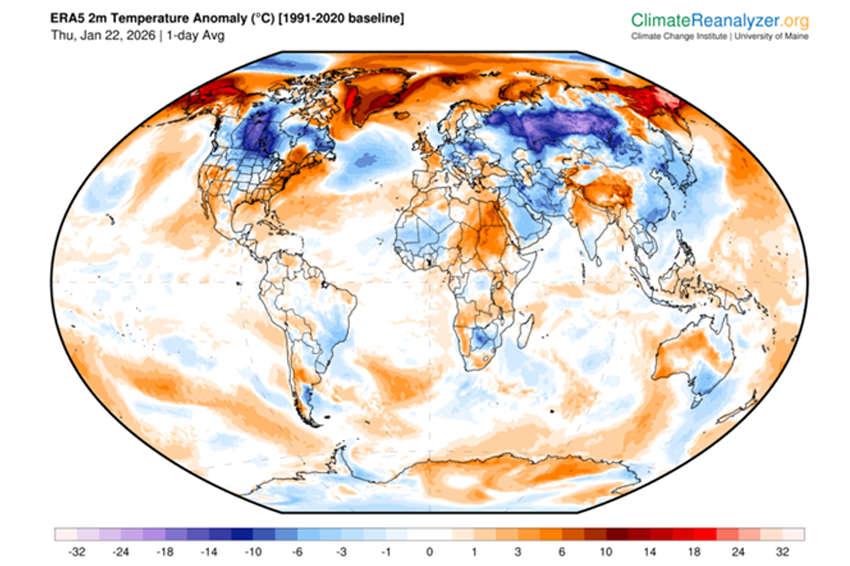

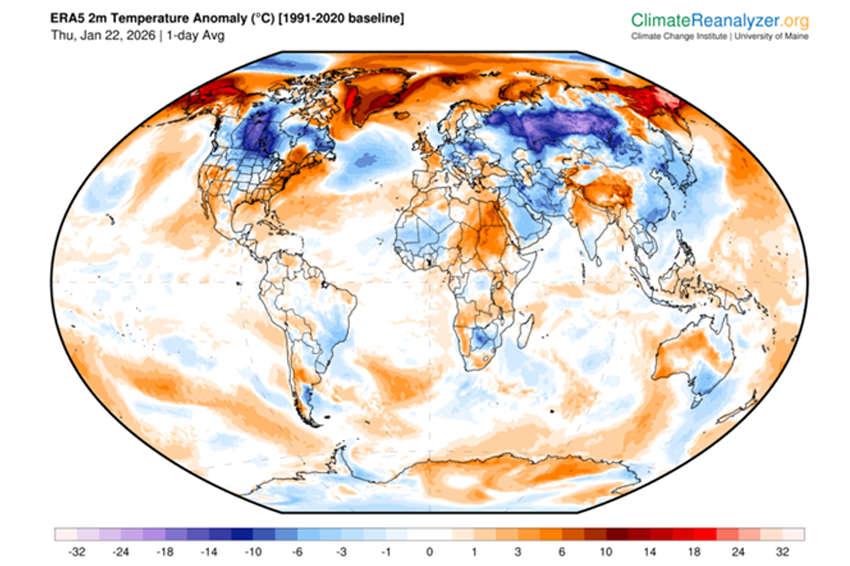

Cold conditions in one place do not necessarily reflect temperatures worldwide. For example, while the United States has been gripped by severe cold, neighboring Greenland recorded unusually warm temperatures over the same week, often above freezing, roughly 20 degrees Celsius warmer than the long-term average for this time of year.

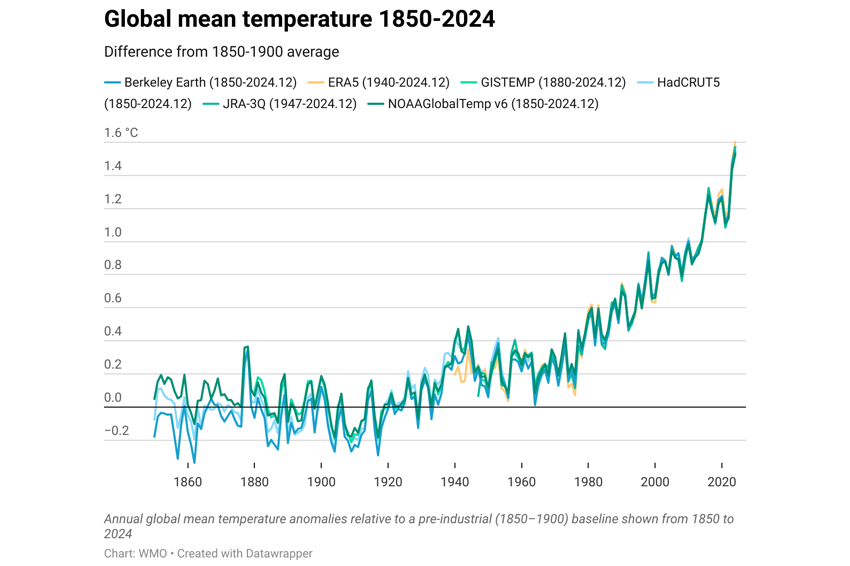

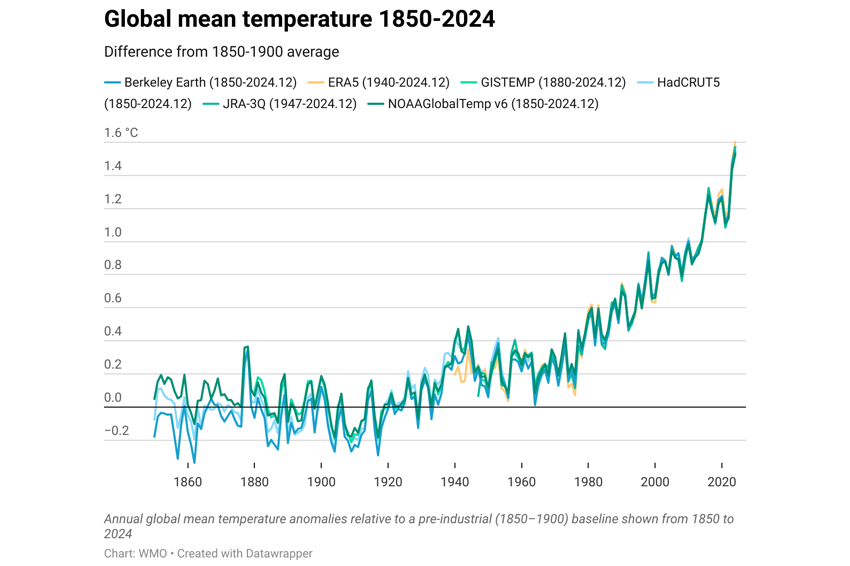

When global temperatures are averaged, the global mean temperature last week was higher than the 1991–2020 average, not lower. This 30-year period is the accepted standard for calculating climate averages. In recent decades, every year has been warmer than those before the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century.

When polar cold moves south

Global warming, or climate change, affects not only average temperatures but also extreme weather events. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, summarizes the scientific consensus on climate change. According to its findings, global warming leads to a significant increase in the frequency and intensity of heat waves, floods and droughts. Cold waves, overall, are becoming less frequent worldwide.

However, regions such as the United States may still experience intensified cold waves rather than fewer of them.

Because Earth is spherical, the polar regions receive sunlight at a less direct angle, spreading the same amount of solar radiation over a larger area. As a result, each unit of surface receives less energy, making the poles colder. The temperature difference between the poles and more temperate southern regions creates pressure differences that drive atmospheric circulation.

6 View gallery

While the US endures extreme cold, neighboring Greenland has recorded unusually warm temperatures. Daily global temperatures relative to the long-term average for the same date, as the cold wave reached the United States

(Photo: Climate Change Institute, University of Maine)

Earth’s rotation complicates this movement, causing fast-moving air currents to flow eastward around the poles rather than north or south. These high-altitude currents, known as polar jet streams, separate cold polar air from warmer air farther south and help prevent temperate regions from freezing.

At times, however, the jet stream bends north and south in wave-like patterns, allowing cold Arctic air to spill into more southern regions, including the United States.

The greater the temperature difference between the poles and temperate zones, the faster and more stable the jet stream tends to be. This is why winter typically features strong, steady jet streams that shield North America and Europe from extreme cold. Global warming is altering this balance.

The planet is not warming evenly. The polar regions have warmed far more than temperate areas, reducing the temperature difference between them. This slows the jet stream, making it more susceptible to disturbances that cause it to meander.

These bends can extend as far south as Mexico, freezing even the southern United States. Because of their wave-like structure, when cold air plunges southward over North America, warm air may simultaneously surge northward, warming places like Greenland. Slower-moving atmospheric patterns also mean that extreme weather conditions can persist for longer periods.

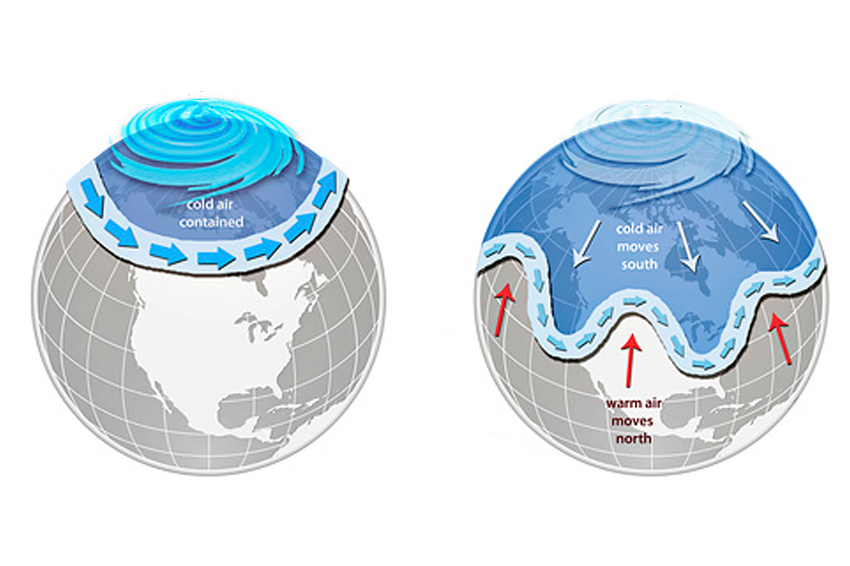

The polar vortex

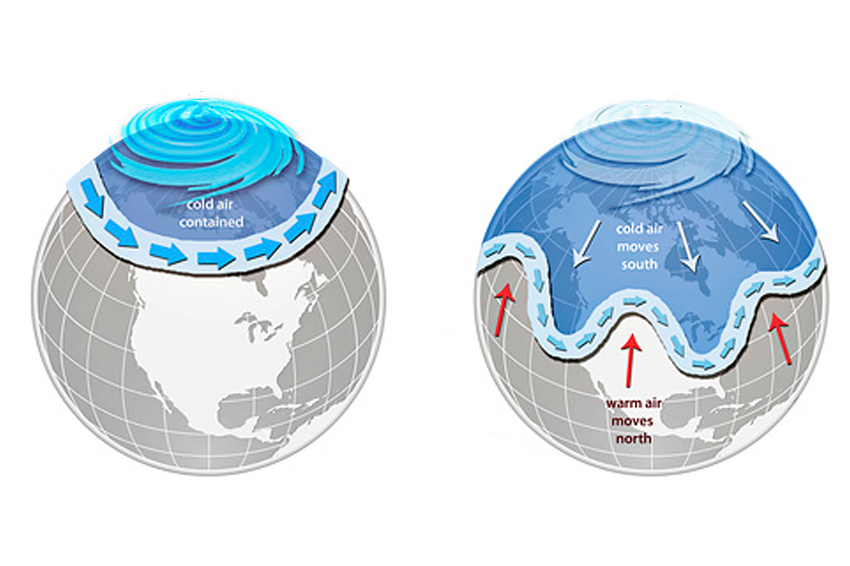

Atmospheric circulation near the poles does not end with the jet stream. A massive rotating body of air, known as the polar vortex, spins above the poles at altitudes of tens of kilometers, above the jet stream. Its behavior is complex and not fully understood, but it plays a critical role in determining whether polar cold remains contained or spills southward.

When the polar vortex is strong, it tends to stay centered over the pole and suppress large jet stream waves, reinforcing the separation between polar cold and temperate warmth. When it weakens, shifts, stretches or even changes direction, it can trigger rapid warming in the stratosphere, the atmospheric layer above the lowest one.

In the weeks following such warming events, the jet stream often becomes more distorted, increasing the likelihood of extreme weather. However, the precise relationship between the polar vortex and the jet stream remains an active area of research.

Amy Butler of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, specializes in these atmospheric dynamics. “The polar vortex does not always influence winter weather in temperate regions,” she explains. “But when it does, the effects can be extreme.”

Some forecasts point to significant disruption of the polar vortex this year, potentially leading to especially cold temperatures across the Northern Hemisphere in February.

Scientists caution that while the polar vortex may be influenced by climate change, the extent of that influence remains uncertain. Butler notes that despite the overall warming trend, some regions may experience more severe winter storms. She emphasizes that additional research is needed to fully understand the long-term behavior of the polar vortex and distinguish between natural variability and climate-driven change.

6 View gallery

When the polar vortex is especially strong, it tends to stay close to the pole and reduce the waviness of the jet stream (left). When it weakens or changes shape, it can increase jet stream meanders and trigger extreme weather (right)

(Photo: NOAA)

The climate crisis is real, and the evidence is clear

Despite the complex and sometimes confusing behavior of the polar vortex, the overall trend of global warming is sharp and unmistakable. Even if some regions experience cold spells, the global climate continues to warm.

Around the world, increasingly sophisticated monitoring systems track Earth’s climate, and there is broad scientific consensus that warming is real and already producing visible effects. We also know with high confidence that human activity, especially the burning of fossil fuels such as oil, gas and coal, is the primary driver of rising greenhouse gas emissions and global warming.

6 View gallery

The trend of global warming is clear and unmistakable: in recent decades, every year has been warmer than those before the Industrial Revolution. A graph shows average global temperatures from 1850 to 2020

(Photo: World Meteorological Organization)

When the United States withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in the early 2000s, other countries followed. European nations and others, however, remained committed to emissions reductions and met their targets. The results were far from perfect, but they significantly reduced global emissions growth and spurred the development of low-carbon technologies.

Today, the Paris Agreement, which replaced Kyoto, faces similar risks following the U.S. withdrawal. The hope is that decision-makers in Israel and around the world will act in line with the scientific consensus, aggressively reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prevent the most severe consequences of the climate crisis. As the public, we also have a role to play in supporting this vital effort.

Dr. Yuval Rosenberg is a researcher at the Davidson Institute of Science Education