Since returning to the White House, President Donald Trump has repeatedly stressed what he calls “mineral independence,” urging the United States to expand domestic mining, processing and manufacturing of so-called critical minerals.

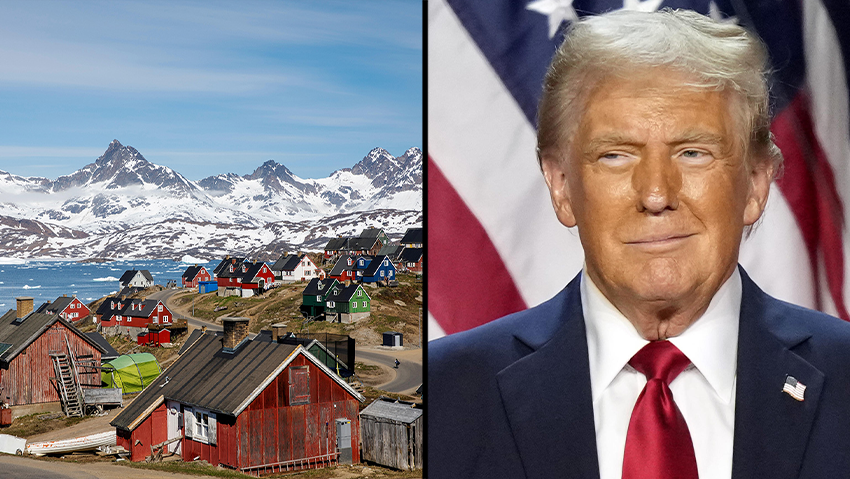

The issue has surfaced across Trump’s agenda — from renewed talk of acquiring or taking control of Greenland, to advancing mineral cooperation agreements with Ukraine and Australia, and to tariff battles with China. At the heart of those moves is Beijing’s dominance of the global heavy metals and rare earths market.

The concept of strategically vital materials is not new. During World War I, Congress passed legislation defining materials essential to public welfare. In 2017, during Trump’s previous term, an executive order formally defined “critical minerals” as resources vital to U.S. national and economic security. Last November, the U.S. Geological Survey expanded its official list from 50 to 60 minerals.

The list is dominated by metals such as lithium, magnesium, nickel and platinum, used across transportation, defense systems, power grids and computing infrastructure. It also includes many rare earth elements, which are essential for renewable energy technologies, robotics, electric and autonomous vehicles, and data centers that power artificial intelligence, big data and the Internet of Things.

China controls most known deposits of heavy and rare metals, both within its borders and through assets acquired abroad. It also dominates the complex separation and refining processes, accounting for up to 90% of global production and about 70% of global supply chains for these materials.

Throughout history, competition over natural resources has fueled conflict — over water, farmland, fishing grounds and fossil fuels. In recent years, that struggle has increasingly centered on heavy metals, especially rare earths such as yttrium, samarium and cerium. Though they have no known biological role, they are embedded in countless products, from smartphones and laser systems to solar cells.

The accelerating pace of technological development has driven demand for a growing number of elements from the periodic table, prized for specific properties such as strength, conductivity, magnetism and optical performance. But increased reliance on these materials carries environmental costs, both local and global.

Mining and processing metals from natural ores require large amounts of energy and water and involve toxic chemicals, including strong acids and bases. The processes generate hazardous waste, wastewater discharges, air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Some elements are toxic or radioactive and can contaminate water sources and agricultural produce, ultimately entering ecosystems and the human body. Improper disposal of electronic waste further compounds environmental and public health risks.

Heavy metals also affect natural physical processes. They influence the movement of elements in soils and water systems and alter the stability and structure of minerals. Yttrium, for example, binds strongly with phosphate, a key component of biological systems and fertilizers. Cerium and samarium stabilize monazite, a mineral used both for rare earth extraction and for producing thorium, a potential nuclear fuel.

Earth’s natural resources are finite. As human populations have grown, extraction, industrial production and consumption have accelerated, releasing vast quantities of natural and synthetic substances into the environment. The result has been air, soil and water pollution, biodiversity loss, damage to public health and a worsening climate crisis.

For years, debate over overexploitation focused mainly on ecosystems and biodiversity. Increasingly, scientists are warning that changes in the planet’s chemical diversity — the type, concentration and distribution of elements and compounds — also pose serious risks to both natural and human environments.

Prof. Adi Wolfson

Prof. Adi WolfsonCritical minerals have become basic building blocks of modern life. But their widespread use comes with hidden costs. Experts argue that reducing consumption at the source, expanding reuse and recycling, and managing these resources responsibly are essential to ensure they remain available for future generations.

Prof. Adi Wolfson is head of the master’s program in green engineering at the Sami Shamoon College of Engineering. He is the author of “The Great Crisis – The Age of Humanity: Between a Macroscopic and Microscopic View” (Pardes, 2023) and “Sustaining Life – Humanity, Society and the Environment: Lessons From the Past and Responsibility for the Future.”