Summer 1975. Despite progress in arms talks between the superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union still have thousands of nuclear ballistic missiles aimed at each other. The United States is recovering from the Vietnam War, which ended with the fall of the South and communist control of the entire country. The Soviet Union is grappling with a deepening economic crisis. Civil wars are breaking out in Cambodia and Lebanon.

Across the globe, a sense of instability prevails against the backdrop of the Cold War and its consequences. And yet, during this turbulent time, two spacecraft from these bitter adversaries meet in orbit. American astronauts speak Russian and shake hands with Soviet cosmonauts speaking English. For a brief moment, it seems possible to forget the wars and nuclear weapons below — to hope that this encounter in space is a sign that there is still hope for humanity.

Changing the rules

The space race was one of the most intense arenas of the Cold War—not because of public curiosity about the universe, but because of its profound military implications. The development of satellite-launching technology in the late 1950s also demonstrated the potential to deliver nuclear warheads via long-range rockets. Satellites also opened new opportunities for espionage and surveillance, turning space into yet another strategic battleground.

In the early stages of the space race, the Soviet Union was the clear frontrunner. It launched the first satellite, Sputnik, in 1957 and, later that same year, sent the first living creature into orbit—well before the United States had managed to launch even a small satellite. In 1961, the Soviets also sent the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space 1961, achieving a full orbit of Earth before the U.S. completed its first suborbital flight. The Soviet Union continued to outpace the U.S. by sending the first woman into space, launching the first multi-person crewed spacecraft, performing the first spacewalk, and more.

6 View gallery

A historic Cold War moment marking the start of a new era. American astronaut Tom Stafford shakes hands with his Soviet colleague Alexei Leonov after docking their spacecraft in spaceA historic Cold War moment marking the start of a new era. American astronaut Tom Stafford shakes hands with his Soviet colleague Alexei Leonov after docking their spacecraft in space

(Photo: NASA)

And what do politicians do when they’re falling behind? They change the rules. Soon after the Soviet Union won the race to put a human in space, U.S. President John F. Kennedy set a bold new goal: to land a man on the Moon before the end of the 1960s. The United States threw its full economic and industrial might into the effort, closed the gap, and eventually overtook the Soviets. In July 1969, Kennedy’s vision was realized—though he did not live to see it—when American astronauts landed on the Moon.

It was precisely after the American victory in the race to the Moon that a period of détente began to take shape on the global stage. This shift may have been influenced by the fact that both superpowers had begun pursuing different goals in space. The United States continued the Apollo program, completing six successful lunar landings by the end of 1972, while the Soviet Union—claiming it had never intended to land on the Moon—shifted its focus to developing space stations in Earth orbit.

6 View gallery

Meetings that paved the way for diplomatic cooperation. Neil Armstrong (third from the left) arriving for his historic visit to the Soviet Union in 1970

(Photo: NASA)

This political thaw was reflected in a series of reciprocal visits: American astronauts traveled to the Soviet Union, and Soviet cosmonauts visited the U.S., often following encounters at neutral venues such as the Paris Air Show. In 1970, less than a year after becoming the first human to walk on the Moon, Neil Armstrong made a goodwill visit to the Soviet Union. These exchanges helped open the door to higher-level diplomatic dialogue and ultimately led to the decision to undertake a joint space mission.

A bilingual mission

In May 1972, U.S. President Richard Nixon and Premier of the Soviet Union Alexei Kosygin signed a Space Cooperation Agreement, concerning “cooperation in the exploration and use of outer space for peaceful purposes”. Signed during a conference in Moscow, the document included a commitment to develop a docking system that would allow American and Soviet spacecraft to rendezvous in orbit—useful, for example, in a rescue scenario.

As in many diplomatic breakthroughs, this political accord followed extensive technical groundwork. Beginning in the latter half of 1971, American and Soviet teams met alternately in Moscow and Houston, reaching key agreements on the design of a common dual-compatible docking system that would allow either spacecraft to assume the active or passive role during the docking process.

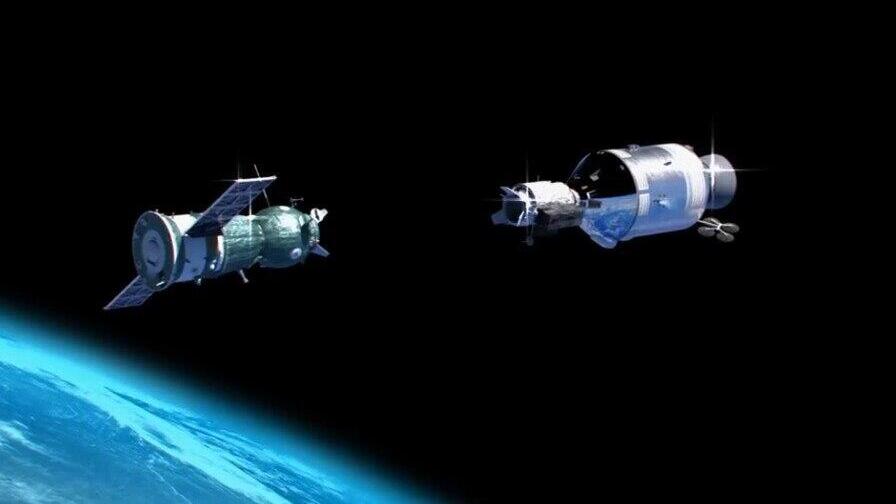

6 View gallery

Commander camaraderie. Stafford (outside the spacecraft mockup) and Leonov exchange jokes during mission training

(Photo: NASA)

The official signing of the cooperation agreement soon led to a broader consensus: a joint mission in which an American Apollo spacecraft and a Soviet Soyuz would rendezvous in space in 1975. However, agreeing on the design of a docking adapter was only the first of a long list of technical and logistical challenges. For instance, one major issue was the difference in cabin atmospheres—Soyuz maintained a nitrogen-oxygen mix at 14 PSI, while Apollo used pure oxygen at just 5 PSI. Transitioning between these environments in terms of pressure differences and different gas compositions could pose serious risks to crew health.

Beyond engineering concerns, the two sides also had to determine how the rendezvous and docking would be conducted, which spacecraft would host joint activities, what those activities would be, and even which language would be used for communication.

In the end, they successfully bridged all the gaps—from lowering the air pressure in the Soviet spacecraft, to jointly selecting scientific experiments, and even agreeing that each crew would attempt to speak the other’s language: the Russians would speak English, and the Americans would speak Russian.

In 1973, following the official crew selection, training for the mission began. The astronauts, cosmonauts, and their backup crews trained alternately in the Soviet Union and the United States, alongside ongoing coordination between engineering teams, flight controllers, and other involved parties. Naturally, intensive language training was also a crucial part of the preparation on both sides.

Naturally, the process was not without friction. Both sides had significant criticisms of each other’s methods and practices. The Soviet design philosophy emphasized automation, with spacecraft built so that ground control could take over operations if necessary, minimizing the crew’s workload. In contrast, American spacecraft required more active involvement from astronauts during flight. The Americans voiced concerns about the safety of the Soviet spacecraft, noting the lack of redundant backup systems compared to U.S. standards. The Soviets, meanwhile, argued that American spacecraft were overly complex and therefore more prone to human error. They also frequently accused the Americans of being arrogant.

In the end, cooperation pushed both sides out of their comfort zones. In the United States, some criticized the idea of an equal partnership with the Soviets, fearing it might lead to the transfer—or theft—of American technological expertise. The Soviets, for their part, had to relinquish some of the secrecy that had long defined their space program. For the first time, they allowed American crews to observe mission preparations, opened their operations to media coverage, and agreed to live broadcasts of the launch, docking, and other mission events.

Veterans and rookies

The Apollo–Soyuz mission, officially known as the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), was something of a reward for the astronauts and cosmonauts who had waited years—or even decades—for the chance to fly. Representing the Soviet Union were Alexei Leonov and Valery Kubasov. Leonov had made history in 1965 by performing the first spacewalk and later trained for a lunar mission that was ultimately canceled before reaching the operational phase. Kubasov had flown in 1969 on Soyuz 6, a mission plagued by technical difficulties. In 1971, both men were assigned to the Soyuz 11 crew, which was intended to be the first to staff a space station. However, a suspicious shadow on Kubasov’s chest X-ray—raising concerns about possible tuberculosis—led doctors to replace the entire crew. That decision likely saved their lives, as the replacement crew perished during reentry when their capsule depressurized.

6 View gallery

A mix of seasoned space veterans and astronauts long awaiting their first mission. From left: Slayton, Stafford, Brand, Leonov, and Kubasov, posing with a model of the docked Apollo–Soyuz spacecraft

(Photo: NASA)

For the Apollo–Soyuz mission, the Soviet team included only two cosmonauts instead of the usual three. This was due to modifications made to the Soyuz spacecraft, including the requirement that the crew wear full pressure suits during certain phases of the mission, particularly in case of docking failure and potential cabin pressure loss.

On the American side, command was given to Tom Stafford, who had previously commanded Apollo 10—the final dress rehearsal before the Moon landing. During that mission, Stafford piloted the lunar module to within 15 kilometers of the Moon’s surface, though he didn’t get to land. His two crewmates on that mission, John Young and Eugene Cernan, later returned to the Moon as commanders of the final Apollo missions and landed there.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Joining Stafford was Donald "Deke" Slayton, one of NASA’s original Mercury Seven astronauts. Slayton was grounded before his first flight due to an irregular heart rhythm, but he remained at NASA, eventually becoming head of the Astronaut Office, where he was responsible for assigning missions to others—all while quietly holding onto the hope of flying himself. After many years, he successfully stabilized his condition and finally earned a seat on the Apollo–Soyuz mission at the age of 51, considered quite old for a spaceflight at the time.

The third American crew member was Vance Brand, who was selected as an astronaut in 1966. He had served on support and backup crews for several Apollo missions and was originally slated to fly on Apollo 18, a mission ultimately canceled due to budget cuts. Later, he commanded two of the three backup crews for missions to the U.S. Skylab space station, but again did not get to fly. After nine years of waiting, Brand was finally assigned to fly on Apollo–Soyuz.

Shaking hands

On July 15, 1975, Soyuz 19 lifted off from the Soviet space base in Kazakhstan. Less than eight hours later, the final Apollo spacecraft launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Following carefully coordinated flight paths, Apollo gradually closed the distance to Soyuz as both spacecraft moved along pre-determined orbits. On July 17, Apollo executed a maneuver that placed it into a rendezvous orbit with the Soviet spacecraft. After a few final trajectory adjustments, Mission Control in Houston transmitted:

“Moscow is Go for docking; Houston is Go for docking. It’s up to you guys. Have fun!”

Commander Tom Stafford took manual control for the final approach. A few minutes after noon on the U.S. East Coast—early evening in Moscow—the long-awaited "click" echoed through the cabin as the two spacecraft successfully docked, 229 kilometers above the Atlantic Ocean.

“Capture! Soyuz and Apollo are shaking hands now!” Leonov announced in English over the radio.

A little over three hours after docking, both crews completed preparations inside the connected spacecraft, including equalizing air pressure. Stafford opened the hatch of the docking module and shook hands with Leonov—a moment broadcast live around the world. The crews exchanged gifts, signed commemorative certificates, listened to a greeting from Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev read on Soviet television, and spoke with U.S. President Gerald Ford, who called to offer his congratulations from the White House.

They later conducted several joint scientific experiments and even shared a meal. Neither spacecraft had enough room for all five crew members at once, so they periodically switched places and each spent at least a few hours aboard the other side’s spacecraft.

After about a day and a half, it was time to part. Each crew returned to its spacecraft, and on July 19, shortly after 8:00 a.m. Eastern Time, Apollo and Soyuz undocked—but their collaboration wasn’t over yet. Apollo maneuvered into a position between Soyuz and the Sun, creating an artificial solar eclipse that allowed the Soviets to photograph the Sun’s corona. Shortly afterward, the two spacecraft docked once more, this time for a practice run without crew transfer. After approximately two and a half hours, they undocked for the final time.

Soyuz returned to Earth the next day. The Apollo crew remained in orbit a few days longer before safely landing on July 24.

Seeds of cooperation

Despite the thaw in relations and the successful cooperation between the rival superpowers, there was no immediate follow-up to the joint mission. Military tensions persisted—and even escalated during the 1980s, particularly with U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s proposed Strategic Defense Initiative, nicknamed the Star Wars program. The Soviets, concerned that the advanced capabilities of the new U.S. Space Shuttle could be used for military purposes, responded by developing a nearly identical shuttle of their own. However, it flew only once, and without a crew.

6 View gallery

The seeds of cooperation sown in 1975 bore fruit nearly two decades later. Deke Slayton (left) and Alexei Leonov share a moment of satisfaction aboard the Soyuz spacecraft

(Photo: NASA)

Ultimately, it was the collapse of the Soviet Union that paved the way for renewed space cooperation. The two sides agreed to build a joint International Space Station. As a stepping stone, U.S. Space Shuttles began docking with Russia’s Mir space station. American astronauts stayed aboard Mir for extended periods of time, while Russian cosmonauts joined U.S. Space Shuttle missions.

The fact that this partnership evolved so smoothly—and that the International Space Station has remained continuously crewed for nearly 25 years, operating effectively even during periods of political tension—is largely due to the spirit of cooperation first established during the Apollo–Soyuz mission at the height of the Cold War. That historic endeavor demonstrated that collaboration in space was not only possible but also mutually beneficial.