“The addiction took everything from me. I lost my family, hundreds of millions of shekels, my status and, most of all, my self-respect. From a wealthy man with a helicopter and a yacht, I was left with nothing — from the very top, I fell to having no place at all.”

So says S.L., 49, divorced and a father of three, once a successful real estate developer who earned a fortune but today is penniless, fighting for his life after years of severe alcohol addiction.

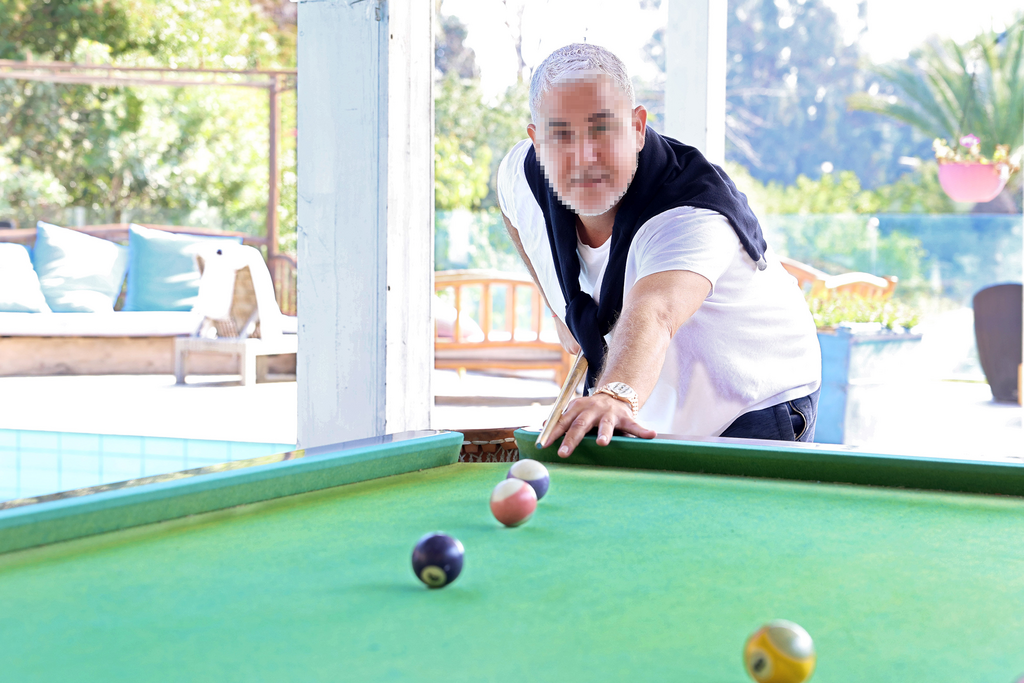

We met him at Villa Balance, a private rehab clinic in the affluent town of Savyon, where he is undergoing his 13th attempt at detox. “I had everything, but I always felt something was missing,” he says.

Born into a well-off family, S.L. grew up spoiled, the youngest of four, with parents who gave him a car the moment he finished military service and cash to spare. “I was in constant hunger for more. If I went out with one woman, I was already looking for another,” he recalls.

The family he later built didn’t quiet that hunger, and he hurled himself into business. “By 42, I thought I had conquered the world. Beyond real estate, I built gas stations and closed a successful exit worth 68 million shekels. The more I had, the more I wanted. I built my family a huge house with a pool, drove a Maserati, bought my wife a sports car, flew everywhere in the world. At the same time, I started drinking, gambling and later snorting cocaine.”

His first rehab attempt, seven years ago, failed. “I understood what it was about, but after a month, I left and went back to using,” he says. Around the same time, his personal life unraveled as he divorced. “As time went on, I felt I was losing my sharpness. I made mistakes in business, sat through key meetings unfocused, thinking only about the next drink, the next line.”

From a respected, level-headed businessman, S.L. descended into slavery to alcohol and drugs. “I acted without thought. I could blow 100,000 shekels in a day on hotels, women, flights, indulgences. I didn’t see my parents, my kids, nothing. Just the bottle and the drugs. Even when I tried to arrange business meetings, I couldn’t concentrate.”

In the past seven years — “the dark period,” as he calls it — S.L. burned through all his wealth. He lost his faith as well. “I used to keep Shabbat, tithe, donate. That’s gone. My kids, who mean the world to me, are angry. I haven’t sat with them for kiddush in seven years. My sisters tried to push me back to rehab, but the disease was stronger. I ended up broke and alone.”

The turning point came a few months ago. Alone at home after heavy drinking, he suddenly lost control of his body. “My hands swelled, my mind went hazy, but before I blacked out I managed to call an ambulance,” he says.

He woke up in intensive care, hooked up to machines. “They told me I had a stroke, caused by an overdose. The day I was discharged, my younger sister — who has been supporting me emotionally and financially, paying for this rehab — took me straight here. After nearly losing my life, I believe this will be the last time.”

The only sign of his former wealth is the luxury watch on his wrist, worth more than 200,000 shekels. He treats it as a relic of a time when, in his words, “I had everything — and nothing at all.”

'We treat lawyers, doctors and CEOs'

Villa Balance, the clinic where S.L. is undergoing treatment, is located in a sprawling mansion with a pool, manicured gardens and trees. Converted into a rehab facility in 2021, it now houses 24 patients between the ages of 18 and 54, most of them in their 20s and 30s.

“The people who come here are addicted to alcohol, drugs or prescription medication. Almost none are first-timers in rehab,” said Yifat Vardi, the center’s director, a trained psychotherapist and group facilitator. “Our patients are high-functioning individuals from Israel’s professional elite—well-known businesspeople, lawyers, doctors, tech workers, wealthy contractors and CEOs. They pay 30,000 shekels ($8,000) a month to try and break free from their dependency.”

Most arrive clean for at least a week before admission to Balance, which is supervised by the Health Ministry. “Even after detox, alcoholics experience cravings,” explained Dr. Ofir Livneh, a psychiatrist and addiction researcher at Columbia University. “Of all addictions, alcoholism is the hardest to treat because of how it affects the brain’s reward system. Alcoholics face especially tough challenges compared to other addicts.”

Before being admitted, each patient must submit a chest X-ray, ECG results and a medical summary. Only then are they invited for an intake meeting with the staff, including Vardi, a psychiatrist, social worker and physician with expertise in narcotics. “We present them with the treatment plan, which involves four professional therapists, two social workers, psychodrama facilitators and counselors who are themselves clean addicts. We explain our approach and spell out the house rules.”

Despite the luxury setting, the process is as painful for wealthy patients as for those with fewer means. The staff maintains the grounds meticulously, while patients choose between private rooms with double beds or shared accommodations. For the first two days, each new arrival is assigned a “shadow” who accompanies them, while restrictions apply: no tank tops, flip-flops or sunglasses indoors, and phones are confiscated during the day.

“The first stage, as in Health Ministry rehabs, is ego-crushing,” Vardi explained. “We follow the 12-step model, based on surrender to a spiritual or therapeutic force. Professionally, we help patients submit and build trust in something or someone outside themselves. Once they’ve reached personal rock bottom, we guide them through a gradual process of admitting the addiction and committing to treatment. The addict’s brain is wired for self-destruction, so we use every possible distraction to break the cycle.”

The daily schedule is rigid. Wake-up is at 6:30 a.m., with the first therapy group at 7:30, where patients share how they feel and whether they woke with anxiety. “These are people unused to speaking openly. Their addictions shielded them in loneliness.”

Though the villa employs cleaners, patients are also responsible for their own rooms, the kitchen and the yard. Neglect earns a punishment—a “result” in villa jargon. The standard program lasts three months, but some stay longer to rebuild confidence.

Alcoholics typically fall into two groups, staff explained: those who drink daily, often throughout the day, and those who binge drink—perhaps only once a week, but in massive quantities.

Alcoholics have a deep tendency to lie—“99% of the time they are hiding something,” said Vardi. “Alcohol addiction is aggressive and ever-present. Unlike drugs, which can sedate, alcohol boosts confidence while also fueling aggression. And it’s an addiction to a legal, cheap and easily available substance—accessible to both the poor and the wealthy. The alcoholic stumbles, slurs words, seems confused and at the same time lives in denial. Because of that denial mechanism, many only reach rehab after years.”

According to Vardi, rehab for alcoholics is particularly brutal on the emotional front. “After the physical detox—shaking, profuse sweating, sometimes even hallucinations—patients may be given anti-seizure medication, sleep aids and limited anti-anxiety drugs in the first week. But then comes what I call the ‘emotional Hiroshima’: everything the alcohol had concealed suddenly surfaces. The patient sees, with clarity, the battlefield and ruins left behind—and it’s terrifying.”

She described how difficult reentry into family life can be. “A sober alcoholic comes home to a household where every habit has been warped by the effort to hide the drinking. Children were too embarrassed to invite friends over, relatives distanced themselves. When the patient returns, they are met with suspicion—because they’ve promised before and disappointed, or were caught hiding bottles in fuse boxes, fire hoses or other creative places.”

Because of the toll on families, social worker Nili Baram regularly conducts family sessions. “It’s how I learn about the family dynamics,” she explained. “We hear anger, guilt and fear about the moment the addict returns home. It’s an incredibly complex challenge—not only for families, but for patients who have become dependent on the protective bubble of the clinic.”

'I arrived here on the verge of death'

N., 18, is one of Villa Balance’s youngest patients—a delicate-looking girl with her hair tied in a ponytail. Despite her age, she had already endured five years of addiction before arriving at rehab.

“I grew up without my mother, with violence from my father’s partner. I suffered trauma and developed rage attacks,” she recalled. “Because of the violence at home, I found refuge outside with much older people who taught me to drink and smoke cannabis.”

At one point, her father left for abroad to run a casino, leaving her alone. “I went to school only when I felt like it and was considered at-risk. My father supported me financially, and in return, I arranged flights and hotels for the Israeli gamblers who came to him. By the time I got here, I was on the verge of death. I was trembling, twitching, couldn’t speak or eat. I went through brutal physical withdrawal. After a week, once I started recovering, the rage attacks returned and I wanted to leave.”

For N., who was used to doing as she pleased, adapting to the strict house rules was difficult. “When they told me to clean my room and the villa, I shouted, ‘Who are you, potted plants, to tell me to clean? Hire cleaners!’ Now I wake up at 6:30, clean and do everything. The staff here patiently helped me peel away the defenses I had built around myself. For the first time, I learned to speak emotionally, to say what I feel. Thanks to the new girl who has grown inside me, I’ll be enlisting in the army next month.”