Scientists at the University of Cambridge believe they have discovered a way in which aspirin — a common and inexpensive pain reliever — may help inhibit the spread of cancer by enhancing the immune system's function.

Animal experiments have shown that the drug helps T cells, a key component of the immune system, identify and destroy cancer cells attempting to spread in the body. Researchers have described the finding as "exciting and surprising," as it could lead to the controlled use of aspirin as a complementary treatment for cancer patients in the future.

However, they caution against self-administering the drug, as aspirin carries significant risks. Additionally, this research is still in its early stages, and it is not yet clear which cancer patients might benefit from taking the drug. The study, recently published in the journal Nature, examined how the immune system responds to cancer metastasis.

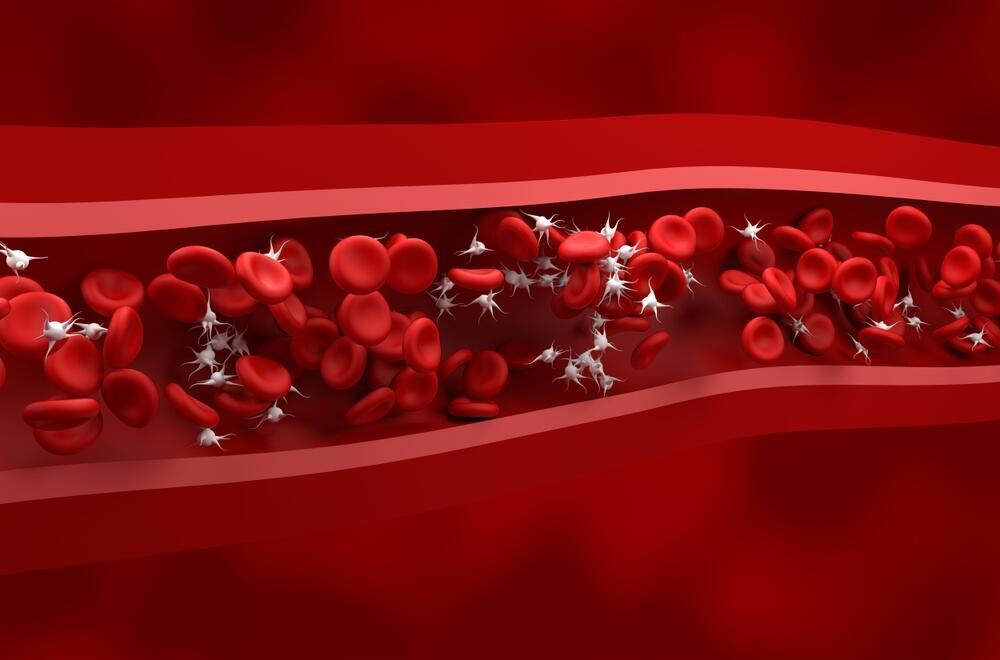

It found that platelets, which are responsible for blood clotting, interfere with T cells’ ability to destroy cancer cells. Researchers discovered that aspirin, which inhibits platelet activity, helps the immune system detect and eliminate cancer cells before they form metastases. This discovery was made by chance. The Cambridge research team was not initially studying aspirin but rather how the immune system responds to cancer spread.

Using genetically engineered mice, they found that animals lacking certain genetic instructions were at a lower risk of developing metastases. Further investigation into the body’s processes revealed that T-cells were affected in a manner similar to the known effects of aspirin. This unexpected finding redirected the researchers’ focus entirely.

Although the findings are primarily based on animal experiments, they provide important insights that could eventually lead to human clinical trials and improvements in current treatment options. Professor Gil Bar-Sela, director of the Beit Shulamit Cancer Center at the Emek Medical Center in northern Israel, commented on the clinical implications of the new research on aspirin and cancer treatment. "It is still too early to determine the clinical significance of these findings," he said. "The big question is whether and how this will translate into a tangible impact on cancer treatment."

"The immune system is complex and influenced by many factors, so additional research is needed to understand the full implications," he added.

Unlike new drugs that require years of development, aspirin is an established and widely used medication. This makes it relatively easy to study its effects on cancer patients, particularly those undergoing immunotherapy — a treatment that activates the immune system against cancer cells.

"Aspirin may serve as a complementary treatment that enhances the effectiveness of immunotherapy, much like other attempts to combine drugs, viruses, or vaccines that stimulate the immune system," Bar-Sela explained.

He noted that a significant advantage is the ability to investigate aspirin’s potential using existing extensive data sets in Israel and globally. A comparison between cancer patients taking aspirin for unrelated reasons and those who do not could provide initial clues about its effectiveness as a complementary treatment. While this is a promising area of research, additional clinical trials are needed before definitive recommendations can be made. Over a decade ago, intriguing data suggested that people who took daily aspirin had a higher chance of survival following a cancer diagnosis.

The key to this lies in the moment when a single cancer cell detaches from the primary tumor and attempts to spread through the body — a process known as metastasis, which is responsible for most cancer-related deaths. At this point, the immune system — particularly T cells, a type of white blood cell — can destroy the cancer cell before it establishes itself in a new location. However, researchers found that platelets, the blood cells responsible for clotting, interfere with T-cell activity, preventing them from destroying cancer cells. Aspirin works by inhibiting platelets, thereby removing the obstacle to T-cell function and enabling them to detect and eliminate cancer cells.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

According to the researchers, using aspirin could be most effective for patients diagnosed early, following treatments such as surgery, to help the immune system eliminate remaining cancer cells. However, they emphasize that cancer patients should not rush to purchase aspirin on their own, as much more research is needed in this area. Currently, certain patients with Lynch syndrome — a genetic mutation that increases cancer risk — already take aspirin as part of their preventive treatment. However, to determine whether more cancer patients could benefit from the drug, further clinical trials are required.

What are the main risks of using aspirin?

- Increased risk of bleeding: Aspirin acts as an antiplatelet agent, preventing blood clotting, which can raise the risk of internal bleeding, especially in the gastrointestinal tract and brain.

- Gastrointestinal side effects: Prolonged aspirin use can lead to stomach ulcers, gastritis and bleeding in the digestive tract, particularly in patients with a history of stomach issues or those taking medications that damage the stomach lining.

- Variable effects depending on cancer type and patient profile: There are differences between cancer types and patients’ genetic profiles, meaning not all patients may benefit from the treatment, and some may face higher risks of severe side effects.

- Interactions with other treatments: Aspirin can affect the efficacy of other medications, including chemotherapy and anticoagulants, increasing the risk of adverse reactions or reducing the effectiveness of certain treatments.

Prof. Gil Bar-Sela Photo: Emek Medical Center

Prof. Gil Bar-Sela Photo: Emek Medical CenterCould aspirin have a greater impact on specific types of cancer?

"Based on available data, aspirin’s effect was more pronounced in breast, stomach and prostate cancers," Bar-Sela said. "In other cancer types, its contribution was minimal or insignificant. Extensive studies, including comprehensive reviews, suggest a reduced risk of cancer recurrence and even prevention of initial cancer development among aspirin users."

In cases of active metastatic cancer, aspirin alone does not appear strong enough to serve as a primary treatment. However, as a supplement to other treatments, particularly immunotherapy, it may offer some benefits — a topic that warrants further exploration. For now, as studies remain in various stages of investigation, the use of aspirin as a complementary treatment is not recommended for all patients. Instead, it should only be considered within clinical trials or under strict medical supervision.