One of the most striking global stories in recent years about the impact of DNA tests is that of an American woman who always knew her biological father was not the man who raised her, but had no way to find him. At 57, she finally decided to take a DNA test.

She spat into a test tube and waited nearly two months for results. The first findings did not identify her father directly but did reveal distant relatives. She began building a family tree until she narrowed the search to a man living about 1,000 miles away. Records showed he had served with her mother in the U.S. Army in Germany during World War II. They had a brief romance, and he was indeed her biological father.

The emotional discovery was bittersweet. The man had never known of her existence, never knew he had fathered a child. What was a life-changing joy for Lisa became a profound shock for her biological father, who suddenly found himself with a daughter, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren. Alongside excitement came anger and frustration as he struggled to process the revelation.

Such stories are not unique abroad. In Israel, similar upheavals surface among adoptees I accompany in their efforts to open adoption files and uncover their origins. Which raises the question: what is really behind the rise of DNA testing?

Science meets the soul

In the past decade, consumer DNA tests have become a common tool for discovering ethnic roots and locating biological relatives. Hundreds of companies now sell genetic tests, with AncestryDNA, 23andMe, FTDNA, and MyHeritage leading the market. Each offers slightly different tools, databases, and regional access.

The process is simple: provide a saliva sample or cheek swab, send it to a lab in the U.S. or Europe, and receive results online within 30 to 60 days. In Israel, where ethnic origin plays a major role in identity, such revelations can deeply affect self-perception, belonging, and decision-making — and sometimes trigger anxiety.

That was the case for Matan (a pseudonym), a 23-year-old adoptee from central Israel. He sought to open his adoption file through the Welfare Ministry’s Child Services to learn about his biological parents. Suspicious that social workers withheld crucial details, and aware of his Middle Eastern appearance despite being raised by Ashkenazi parents, he decided to take a DNA test abroad.

The results confirmed his heritage as Iraqi and Syrian-Lebanese and connected him with two second cousins — one in New Jersey, the other in Ra’anana. The discoveries left him torn: should he reach out to them? Could they lead him to his parents? And should he tell his adoptive family?

Shattering family illusions

The availability of DNA testing has created painful surprises for others. In one case, a young groom took the test at his pregnant wife’s urging. To his shock, the results revealed he had been adopted in Romania, despite believing his whole life that his parents were biological. The revelation caused deep trauma — precisely the kind of scenario Israel’s adoption of secrecy laws aims to prevent.

In Israel, genetic testing without court approval is prohibited, largely out of concern for exposing cases of mamzerut — children born from halachically forbidden relationships. A child of a mamzer is also classified as one, and under Jewish law cannot marry in Israel. According to rabbinical court data, about 200 people in Israel today are classified as mamzers or suspected mamzers.

To avoid such declarations, rabbinical authorities resist recognizing mamzerut, and Israeli law bans consumer DNA testing. Still, tens of millions worldwide have taken tests that cost as little as $100 to $200. Companies also use anonymized data for medical research, tracking genetic diseases, and human migration patterns.

When the past comes back

Alongside benefits, DNA testing raises serious privacy concerns. One woman in her 30s from Kiryat Haim refused to take a test, fearing her genetic data could be misused. “My DNA has value,” she said. “I don’t want just anyone to access it or exploit it.”

4 View gallery

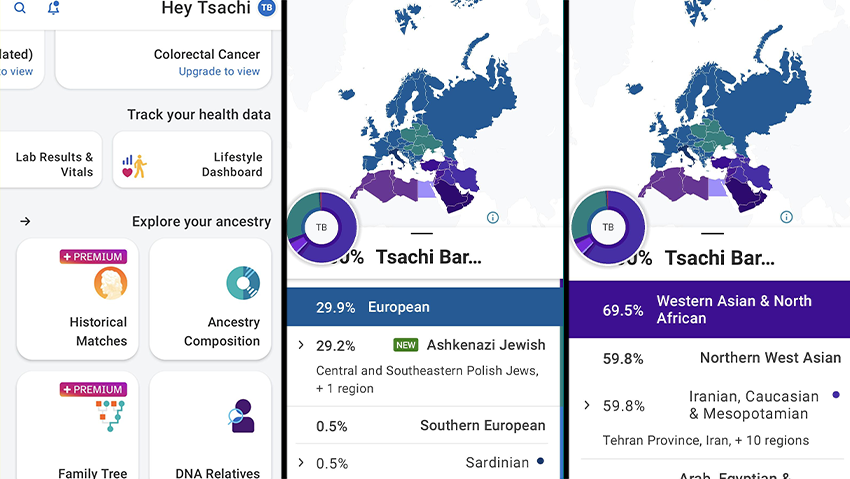

Tsachi, before taking the DNA test, found a biological cousin and another 1,497 relatives of varying degrees

(Tsachi, before taking the DNA test, found a biological cousin and another 1,497 relatives of varying degrees )

Her fears are not unfounded. In March, testing giant 23andMe filed for bankruptcy protection, raising alarms about the fate of its massive genetic database. Although the company was later acquired by a research fund that pledged to protect user privacy, trust was shaken.

Law enforcement use of private genetic databases has also sparked debate, as authorities in some countries tap into them to identify suspects or victims.

Despite the risks, the global market for DNA ancestry and family-finding tests continues to grow rapidly. As someone who opened his adoption file at 47, took a DNA test, and discovered a biological cousin — along with nearly 1,500 other relatives — I believe the tests can be transformative and deeply moving. But it is critical to remember: genetic data is the most sensitive kind of personal information. It must be handled with care.