One of the most intriguing fields today is early diagnosis — identifying subtle changes in the body at a stage when a person feels completely healthy. A new study in blood cancer research demonstrates how a simple blood test may open a window of opportunity for monitoring, prevention and personalized treatment.

A study called PROMISE began at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at Harvard University in the United States and aims to detect a blood disease known as multiple myeloma at its benign stages, long before symptoms appear.

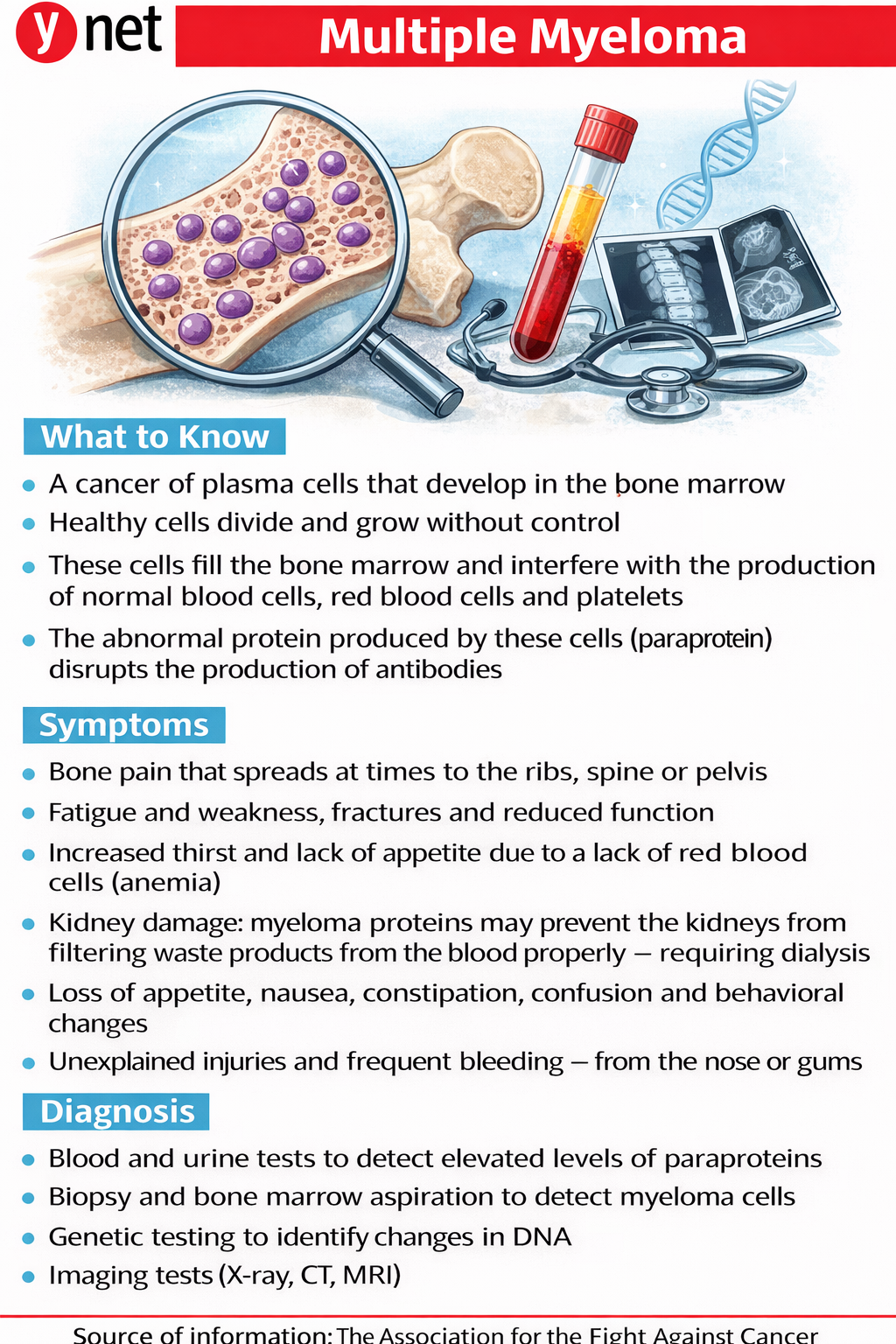

Myeloma is a cancer of plasma cells in the blood — the cells in the bone marrow responsible for producing antibodies and protecting the body from infection. When these cells become cancerous, they multiply uncontrollably and damage the bones, kidneys and normal blood production.

It is now known that nearly every myeloma patient began with a quiet, benign precancerous condition called MGUS. In this state, plasma cells produce a small amount of abnormal protein but without organ damage or symptoms. MGUS can persist for many years before progressing to active disease. A more advanced intermediate stage, known as smoldering myeloma, involves a higher disease burden and a significantly greater risk of developing active illness.

The goal of the study, led in Israel by Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (Ichilov), is to identify healthy individuals in both the benign and smoldering stages. The hematology-oncology departments at Soroka Medical Center and Rabin Medical Center (Beilinson) have recently joined the research.

The study focuses on first-degree relatives of myeloma patients, who have been found to face a higher risk of developing the disease than the general population. Accordingly, 228 healthy, asymptomatic relatives were recruited, half of them under the age of 50. Participants underwent highly advanced and sensitive blood tests capable of detecting minute amounts of abnormal protein — long before standard blood tests would identify anything unusual.

Despite their relatively young age, about 11.4% of participants were found to carry the precancerous condition — a significantly higher rate than in the general population, where prevalence is about 3% among those over 50.

Moreover, several participants who had been considered completely healthy were in fact found to have smoldering myeloma — a stage with a higher risk of progression to active disease. Without the study, they might only have sought medical care years later, after suffering bone or kidney damage. Early detection enabled them to enter close monitoring programs and possibly receive innovative preventive treatment that delays symptoms and may even postpone the need for more intensive therapy.

One of the key findings of the Israeli research involves an innovative epigenetic test developed Project Sanguine in collaboration with JaxBio Technologies. Traditionally, distinguishing between MGUS, smoldering myeloma and active myeloma required a bone marrow biopsy — an invasive and uncomfortable procedure. The epigenetic test, however, examines not the DNA itself but the “switches” that turn defective genes on or off. Diseased cells have a unique epigenetic signature that can be detected in the bloodstream. Through this simple test, it is possible not only to identify the presence of disease but also to distinguish with high accuracy between benign, smoldering and active stages.

This test allows physicians to monitor MGUS in relatives of myeloma patients and detect changes in disease development before symptoms appear.

In the past, the approach to smoldering myeloma was “watch and wait” — monitoring patients until symptoms developed. New studies, including those conducted in Israel, show that early intervention with relatively mild treatments can prevent irreversible organ damage, delay the onset of active disease and in some cases even extend life expectancy.

Professor Irit AviviPhoto: Ichilov spokesman

Professor Irit AviviPhoto: Ichilov spokesmanResults of the PROMISE study in Israel show that the risk of MGUS increases with age and is slightly higher among first-degree relatives of myeloma patients. These relatives are advised to consider screening tests in order to detect the disease at an early stage and prevent future complications.

We are standing at the threshold of a new era: blood cancer can be identified while the body still feels completely healthy, patients can be monitored closely, and physical damage — usually caused by a disease that developed silently — can be prevented.

Professor Irit Avivi is the director of the Hematology Division at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center-Ichilov Hospital