Last month, during a festive military parade in Beijing, an unusual conversation was recorded between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping. The cameras and microphones captured Putin musing aloud about the possibility of repeated organ transplants, ones that would allow a person to stay young forever. The words, broadcast around the world, sounded for a moment like a scene from a science fiction film, but they reignited the disturbing yet fascinating question: how close are we really to turning the vision of life extension into medical reality?

5 View gallery

The microphones picked up the conversation. Meeting between Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un

(Photo: AFP PHOTO/KCNA VIA KNS)

This isn't the first time news has been published about the Russian president's attempts to defeat the angel of death. Last year he ordered the establishment of a national research center aimed at developing innovations in the field of life extension, from technologies for delaying cell aging to advanced neurotechnologies.

His longtime associate, Mikhail Kovalchuk, leads projects in Russia in the field of immortality, including investments in technologies for printing organs from laboratory cells. Putin's eldest daughter, Maria Vorontsova, an endocrinologist by training, has received massive government grants for research in regenerative medicine and cell renewal, and she's involved in genetic projects connected to the Kremlin.

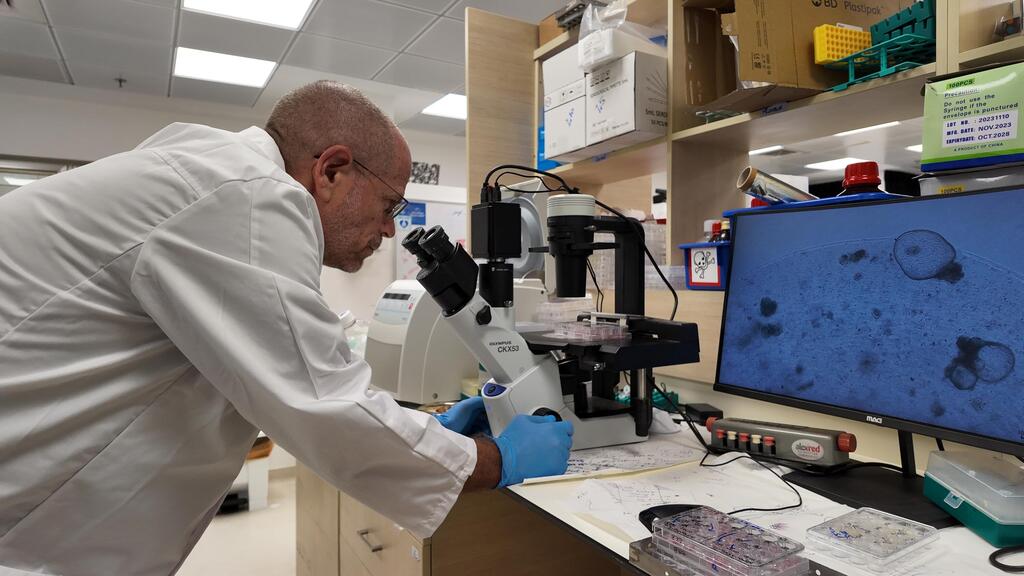

But does such a possibility—repeated organ transplants that would allow one to live forever—sound like an imaginary vision or an emerging scientific reality? According to Prof. Benjamin Dekel, director of pediatric nephrology and the Institute for Stem Cell Research at the Edmond and Lily Safra Children's Hospital at Sheba Medical Center, and director of the Sagol Center for Regenerative Medicine at Tel Aviv University—there's a kernel of truth in it.

"It's clear that in the aging process, organs increasingly fail and function less well, and if you put new organs in their place you can extend their function and prolong life. There's definitely logic in it," he says. "Aging, even without disease, can lead to dysfunction of internal organs, for example in the kidneys. Their function declines from aging processes. So theoretically Putin is absolutely right: there can be an indication of an organ finishing its course as part of aging processes, or as a result of disease, and you bring in a new organ."

However, reality is still far from the vision. "Today, for this to be realistic, we need the barriers to organ transplantation to be removed," Prof. Dekel emphasizes. "First of all, you need to find a donor, and then you need to take complicated medications for life, anti-rejection drugs that cause significant side effects. I don't think a person would agree to take these drugs if they don't have a disease, and therefore it's not realistic at the moment."

According to him, for the idea to become reality, two conditions must be met: an inexhaustible supply of organs, and the ability to transplant them without needing anti-rejection drugs. "If you solve these barriers, then suddenly, since surgeries are becoming technically very feasible, you can talk about a reality of replacing organs when they age," he explains.

To overcome the supply limitation, Prof. Dekel explains, two main research directions are currently developing. The first: using organs from genetically engineered pigs. "One concept says: let's transplant organs from pigs to humans. It's called Xeno-Transplantation. Increase the possibility of more organs for transplantation. The problem is that in transplantation from pig to human, the immune rejection is even more complicated and difficult. Recently they're dealing with this barrier by managing to genetically engineer the pigs, so that the molecules related to immune rejection won't operate. Today there's genetic editing—this is very advanced: genetically editing the genes of the immune system so that our body, the human's, won't reject the pig's transplant. Sometimes dozens of genes are edited simultaneously."

According to him, in recent years several initial attempts have already been made: "There have been several recent transplants of pig organs: kidney, heart and so on in the US. That's one way. But we're not there yet. Putin needs to put a lot of money into this research. It's not easy to silence the genes responsible for immune rejection in such a way that there will be no immune rejection at all. It's complex. And you also need to remember that pigs have infections that can cause us problems. That is, the transplant carries with it all kinds of viruses that can cause infectious diseases in the transplanted human."

And yet, despite the limitations, Dekel is optimistic about the potential: "It's a promising direction. I agree that if we know how to solve this issue of rejection from pig to human in such a way that it becomes common practice, then Putin is right—he'll have a supply, there will be pig farms that will be potential donors, and go ahead."

The second direction takes place in laboratories, where researchers try to create organs from stem cells. This is a particularly ambitious field, since producing complete internal organs is much more complex than producing cells or tissues. "You can create cells, you can maybe create tissues, but complete organs, that's complicated," Prof. Dekel explains. "It's very difficult to build and also imitate evolution in the laboratory, to imitate human development in the laboratory. And still, here too there are advances: recently we achieved a breakthrough when we transplanted kidney tissue, but we're still talking about tissue, components, not a complete organ."

One of the advantages of growing organs in the laboratory is the possibility of creating them from the person's own stem cells, thereby preventing immune rejection. However, this too has limitations. "Many times you don't want to produce a new organ from the person himself, you want someone completely healthy," Prof. Dekel explains. "Say a 75-year-old person, perhaps he'll want very young stem cells ready for use. And therefore today there's a possibility to edit the stem cells that build the organ, to silence the genes responsible for immune rejection, and then build a small kidney or small liver and transplant them. If you succeed with stem cells from a foreign donor in editing and silencing the immune system genes, you have an inexhaustible supply of organs that you grow in the laboratory and they have no immunological identity. They can serve for transplantation without immune rejection."

And another breakthrough has already proven itself: "Not long ago they took pancreas cell lines from a foreign human, genetically edited them and disabled the genes responsible for immune rejection," Dekel describes. "They transplanted the engineered cells into insulin-deficient people, and these became pancreatic islet cells that produce insulin. They weren't attacked by the recipient's immune system, and this is already considered a breakthrough."

The million-dollar question: how do you replace the brain?

But to live "forever" requires more than replacing parts: even if we succeed in building an infinite supply of kidneys, livers and hearts, the big question remains that doesn't yet have an answer: what do we do with the brain. Life extension through organ replacement could get stuck where memory, thinking and personality begin to crack.

"These combinations of stem cells and regenerative medicine (a field of medical research focusing on healing defects in the living body through creating new organs/tissues or cell therapy with the goal of starting a regeneration process in the damaged area) open up infinite possibilities here. The question is what to do with the brain," Prof. Dekel agrees.

"I always say: you'll have new organs, but what will you do if you're demented?" he says. "How can cognitive abilities be improved? That's a fascinating question. There are now for example attempts to transplant cells that secrete dopamine in Parkinson's patients, a disease that manifests in dopamine deficiency in the brain. You transplant dopamine-producing stem cell lines and it's quite amazing."

But here comes the wall of reality: "This can help with Parkinson's disease, but currently in all neurodegenerative diseases we have no way to improve cognition, higher functions, memory and thinking. So I say, Putin can be with new organs, but the question is how he'll function."

And still, if you listen to Prof. Dekel, the vision is far from being completely fictional. Looking to the distant future, he describes a scenario that almost sounds like a visit to a garage, but this time not for a car, but for our body.

"You can theoretically reach a situation where you have like some kind of garage of different options to replace organs," he says. "Think about it: you'll have an app—you'll order organs. You come, choose an organ, receive an organ and that's it. If you see you're aging and you want to continue your life more—what, won't you go in? You'll need a surgical operation, admittedly, but there's definitely truth in it. As science advances and the understanding of mechanisms related to immune rejection and the mechanisms of regenerative medicine become more and more applicable—I have no doubt at all."

According to him, once you have biological principles, implementation takes time, but arrives. "When I was a student they talked about Xeno-Transplantation all the time, and here there are already transplants in humans from pigs. When I was a student 35 years ago, we didn't know all the rejection mechanisms, we weren't aware of the therapeutic possibilities and the options of genetic editing. There's a fundamental difference between science and medicine. We always underestimate the implementation time. It takes much more time than planned. But it will happen. I have no doubt."

5 View gallery

“You’ll have an app – order organs. You come, choose an organ, get the organ, and that’s it.”

(Photo: Shutterstock)

But until the day arrives when we sit back and browse through an organ catalog, already in the near horizon, more modest but far more practical breakthroughs are emerging. We're not talking about replacing a complete organ, but stopping the deterioration of what exists.

"Before complete organs come in, we'll have ways to prevent the deterioration of existing organs, and that's more realistic. That's what we're working on: molecules that stem cells secrete to prevent deterioration. This is a reality that will exist within a decade. Complete organs I still find hard to predict. But that will also come."

Ultimately, even if we reach an era when organs are replaced like spare parts in a car, the big question won't disappear: what will we do with the additional years we'll gain, and what will remain of our human identity when the body is no longer the main limitation? Putin may imagine a world where eternal life is a technical matter of repeated transplantation, but science reminds us that life is much more than our heart, liver or kidneys. Life extension may be able to postpone the angel of death—but it also obligates us to ask how we want to live, not just how long. And perhaps—perhaps, these are the truly essential questions.

First published: 18:16, 10.03.25