Scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science say they have developed a novel immunotherapy approach designed to overcome resistance in cancer patients who do not respond to existing treatments.

The new treatment, detailed in the journal Cell, targets specialized immune‑suppressing macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. These macrophages express a receptor called TREM2 and have been shown to contribute to poor responses to therapy and decreased survival in cancer patients.

3 View gallery

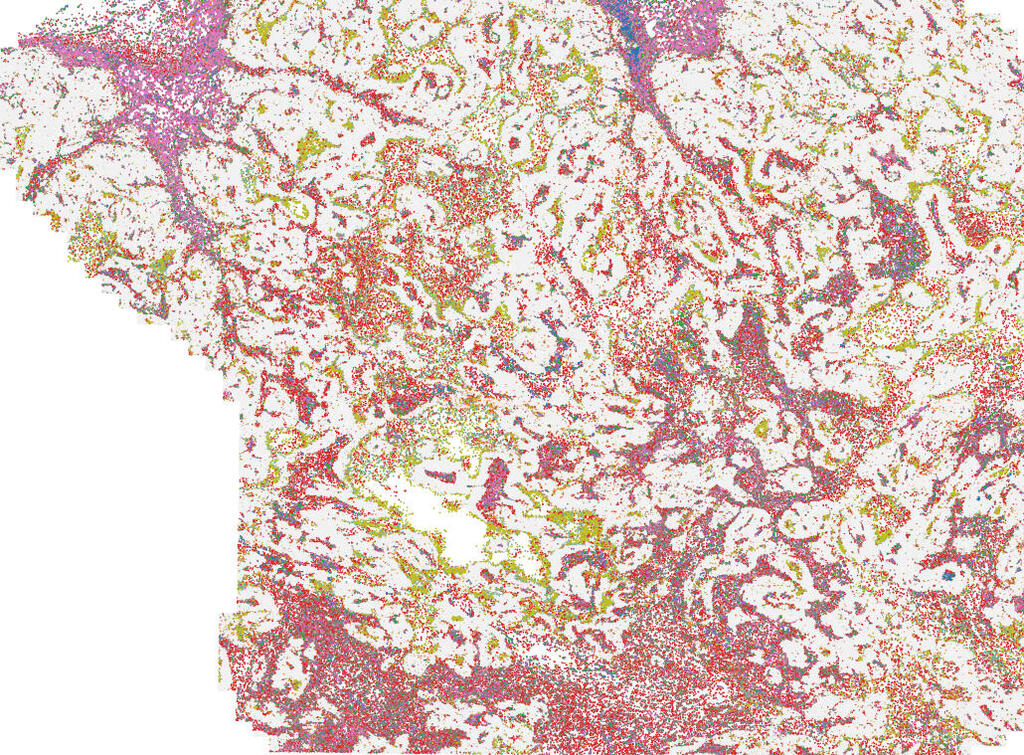

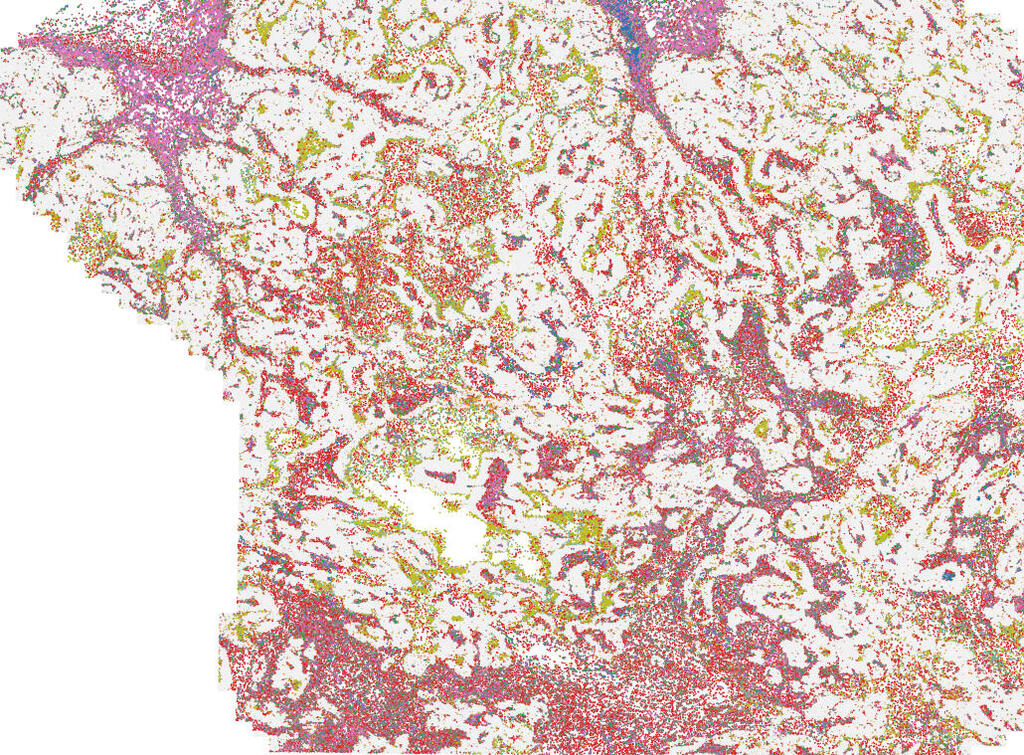

The mapping of spatial immune architecture in human breast cancer tissue (tumor cells are in gray) reveals close proximity of macrophages (brown-orange) and exhausted killer cells (light pink-purple)

“As tumors hijack macrophages to suppress immune responses and promote growth, our goal has been to re‑educate these cells rather than remove them,” said Ido Amit, director of Weizmann’s Immunotherapy Research Center.

The team, led by Michelle von Locquenghien, Pascale Zwicky and Ken Xie, created a new class of biological molecules called MiTEs (Myeloid‑targeted immunocytokines and natural killer/T‑cell Enhancers). These molecules both block TREM2‑expressing macrophages and deliver a cytokine known as IL‑2 to activate other immune cells in the tumor.

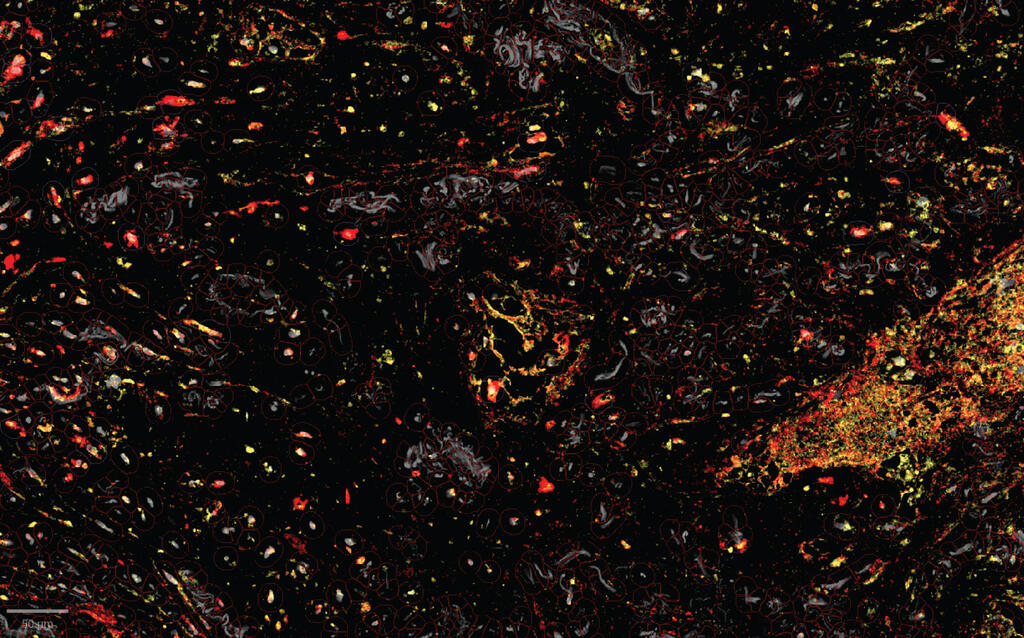

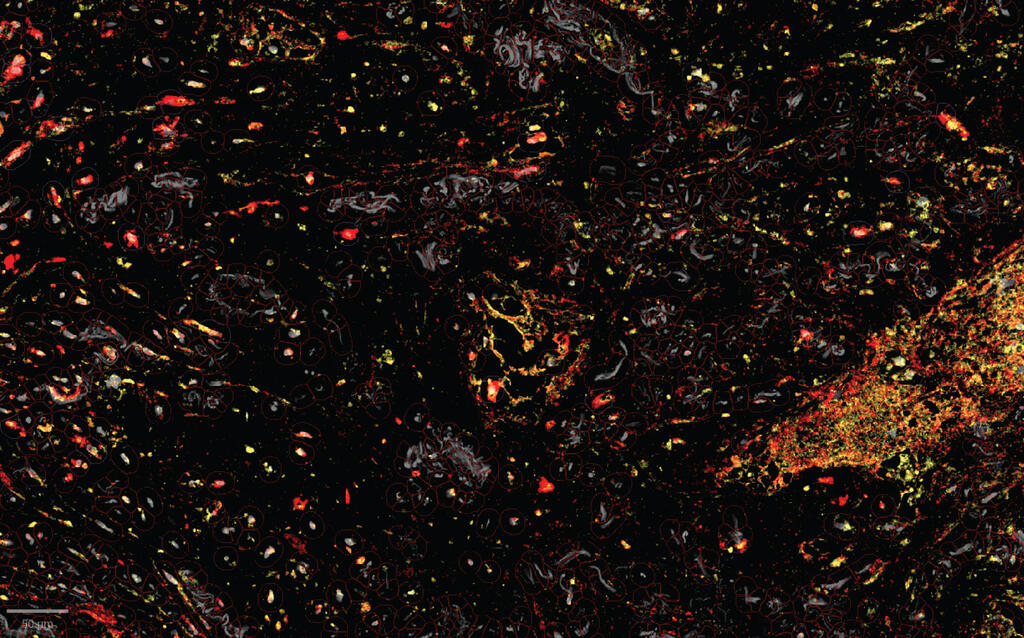

Crucially, the researchers engineered MiTEs with molecular masks that keep the IL‑2 component inactive while circulating in the body. The mask is removed only by tumor‑specific enzymes, enabling activation exclusively within the tumor and reducing the risk of harmful widespread immune reactions.

“The dual function of MiTEs enables them to attack the tumor from multiple immune angles at once,” von Locquenghien said. Zwicky added that because MiTEs act through immune mechanisms common to many cancers rather than relying on tumor‑specific antigens, they could have broad applicability.

3 View gallery

Human lung cancer tissue under a microscope; the enzymes (yellow) that unmask the immune-activating molecules are found near the TREM2 receptors (red) of the tumor-assisting macrophages; this targeted unmasking can prevent damage to healthy tissues

Using spatial transcriptomics, the researchers mapped gene activity in human tumors at single‑cell resolution and found TREM2‑carrying macrophages frequently located next to exhausted immune killer cells. Xie said that insight led to the design of molecules that block the suppressive macrophages while simultaneously energizing killer immune cells.

In preclinical tests in mice, MiTEs caused tumors to shrink and triggered extensive immune remodeling of macrophages and killer cells. Tests on human renal‑cell carcinoma tissue samples also showed robust immune activation, including awakening of killer cells. Preliminary results suggest MiTEs work synergistically with existing checkpoint inhibitors and could be combined with chemotherapy and radiation in future studies.

The findings offer a blueprint for a new generation of programmable, safer immunotherapies capable of overcoming resistance in a wide range of cancers. “By understanding the tumor’s own defense mechanisms, we can turn them into opportunities,” Amit said. “With MiTEs, we may have found a way to convert the tumor’s shield into the very weapon that defeats it.”

Other contributors to the study included Dr. Diego Adhemar Jaitin, Dr. Fadi Sheban, Dr. Chamutal Gur, Reut Sharet Eshed, Eyal David, Kfir Mazuz, Dr. Roberto Avellino and Dr. Assaf Weiner of Weizmann’s Systems Immunology Department; and Dr. Adam Yalin, Dr. Florian Uhlitz, Caroline Jennings Marin, Dr. Ankita Sankar and Devin Mediratta from Immunai in New York.