At 50, Avivit Malka Ben-Gaon knows post-trauma intimately. The two share a long and complicated relationship.

As a veteran therapist and director of the Gallop Center for Trauma Rehabilitation with Horses, she has learned to recognize the frozen gaze, the sudden bursts of anger, the shallow breathing—the body that struggles to trust again.

Today, she works with soldiers and civilians wounded in the war. But growing up alongside a father suffering from untreated combat trauma, she didn’t yet have a name for what she was witnessing at home. Years later, after surviving a devastating accident that also took the life of her fiancé, she finally understood—and began her own journey toward healing, for herself and others.

Living with a father haunted by war

“My father, Eliezer Malka, fought in the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War,” says Ben-Gaon, now married to Gilad and mother of Ela, Ofir and Nevo. “Sometimes he would have these episodes—sudden anger, shouting—and we just thought that was his temperament. Back then, no one even knew what post-trauma was. I remember being sent as a little girl to the pharmacy to pick up his sedatives without understanding why. They told me to say he had a heart condition.”

Only years later, when she began working as a trauma therapist with combat veterans, did the puzzle pieces fit together. “I asked my mother if it was possible that Dad had post-trauma, and she said, ‘Avivit, back then, no one knew what that was. The doctor just said it happens a lot after wars—take some pills and go home.’ That’s how we lived. He went through terrible things. He was afraid to go to the bathroom alone, afraid of closed spaces, he cried at night.”

At ten, her father was diagnosed with lymphoma. Though he recovered, she says, “He was never the same person again. The symptoms just worsened. I lived in constant anxiety. He was terrified for us, always saying, ‘If I’m not here, no one will take care of you.’ He knew his time was short and wanted us to learn how to stand on our own. He died when I was sixteen.”

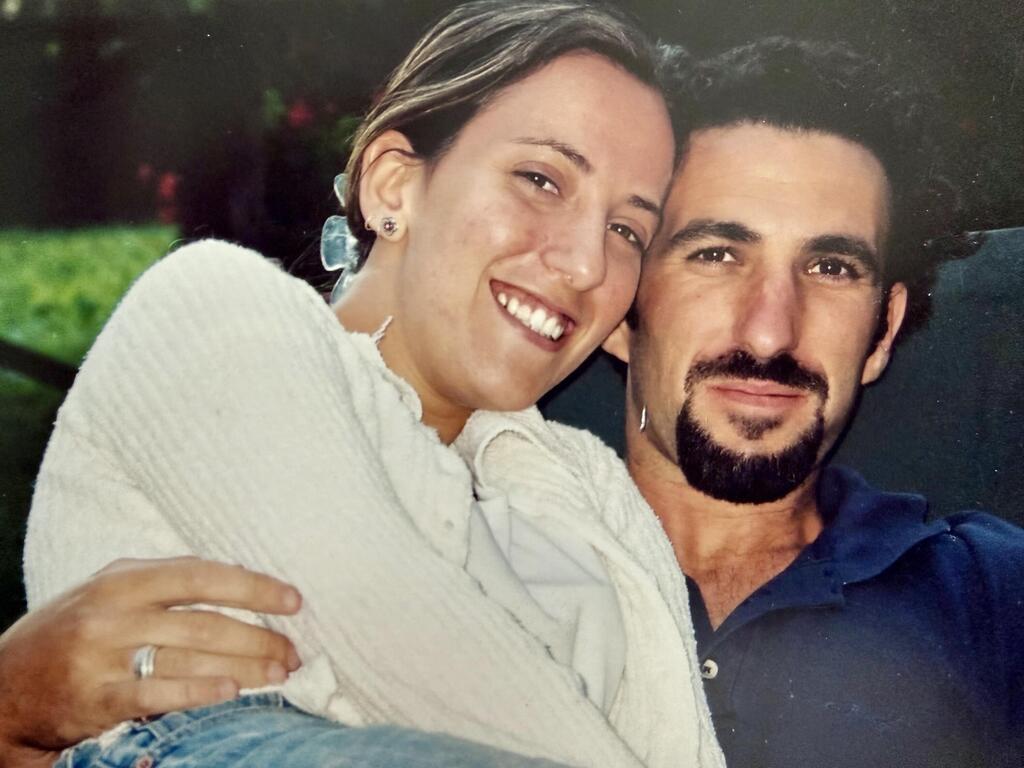

Losing her fiancé in a crash

Less than a decade later, Ben-Gaon found herself back in that same space of fear and loss. She was 25, newly engaged to her longtime partner Dotan. “We had been together four years, planning a wedding, talking about the future,” she recalls. “We had just come back from a year in Kenya and were settling in Israel, staying for a while with our parents, looking for an apartment.”

In June 2000, on their way to work, disaster struck. “We were riding a moped downhill from Rishon LeZion when the front tire exploded. I remember Dotan reaching his arm back to protect me, and then the handlebars went wild. We skidded for 24 meters (about 79 feet) before hitting the guardrail.”

“I was thrown onto my back and couldn’t breathe. Then I took my first breath and screamed like I never had before. I saw Dotan lying motionless on the road. People ran from their cars—some to me, some to him. Someone tried to resuscitate him. I lay on my stomach, facing him, just staring.”

“It took 40 minutes for the ambulance to arrive. I crawled toward him, held his leg, screamed, ‘Doty, get up!’ They kept trying to revive him, and I saw blood coming from his head. I shouted, ‘Stop! You’re hurting him!’ I was lying in a pool of blood. That image never leaves me, even 25 years later.”

Eventually, she was loaded into an ambulance. “Someone closed the door and asked, ‘What about the guy?’ and the answer came: ‘The dead man is in the other ambulance.’ I already knew, but hearing it broke me completely. My body was shaking uncontrollably.”

Ben-Gaon suffered serious injuries—burns on the right side of her body, broken ribs an open knee wound and nerve damage. “I spent three days in the hospital,” she says. “They released me in an ambulance to attend the funeral, with a medic and a wheelchair, then brought me back. Everyone kept saying, ‘You’re lucky to be alive.’ And I thought, ‘What luck? This isn’t luck—it’s punishment.’ Living with that pain felt unbearable. I was shattered.”

The healing power of horses: from despair to renewal

Ben-Gaon had learned what every trauma survivor eventually discovers — sometimes the pain is simply too much to bear. That realization came to a breaking point one day.

“I had to shower three times a day for the burns — dressings, ointments, excruciating pain,” she recalls. “One day, I asked my sister to leave me alone for a few minutes. I just cried and cried. I felt like I wanted to end it all. My sister knocked on the door and said, ‘Avivit, I’m coming in.’ She found me sitting on the shower stool, sobbing uncontrollably. She looked at me and said, ‘Listen, I see you. But if you’re not here, I’m not here either. If you go through with this, you’re taking responsibility for both of us.’”

Two weeks later, her older brother came to visit. “He told my mother, ‘Pack her a bag. I’m taking her with me. She can’t stay here,’” says Ben-Gaon. “He’s been raising horses since he was sixteen — he’s fifteen years older than me — but I had never really been part of that world.”

That day, she says, changed her life. “He put me in the car and drove straight to his ranch. He sat me down by a wooden table that’s still there today, right by the horses’ pen, and told me, ‘This is your place. You’re not leaving until you decide you’re ready. When that day comes, you’ll get up and go. Until then, this is home.’”

She didn’t yet realize how prophetic those words would be. “The longer I sat there, the horses started coming closer. They’re such curious creatures. They stood diagonally across the fence, sniffing me, approaching. Slowly, I began stepping inside the pen, standing among them. They’d lower their heads beside me, and I’d cry. But this time, it wasn’t the same cry from the shower — the one that wanted it all to end. It was a cleansing cry. A release. I didn’t understand what the horses were doing to me, but I knew I wanted to be with them all the time.”

Eventually, she returned home with renewed strength and decided to begin therapy. “I started seeing a psychologist, talking, but I left each session with the same pain.” Six months later, she tried returning to work, but couldn’t function. “I found myself back in a life of alcohol and late-night smoking. On the outside, I was back to normal; inside, I was lost. The only constant was the horses. I kept going back every week without knowing why.

"I started having bursts of rage. I lost people, I withdrew. Everything looked dark. I quit photography, started working at a travel agency and tried to start over — but inside, everything was burning. One day at work, I just exploded. I came home in tears, put on a CD and heard a song called Great Hosanna.

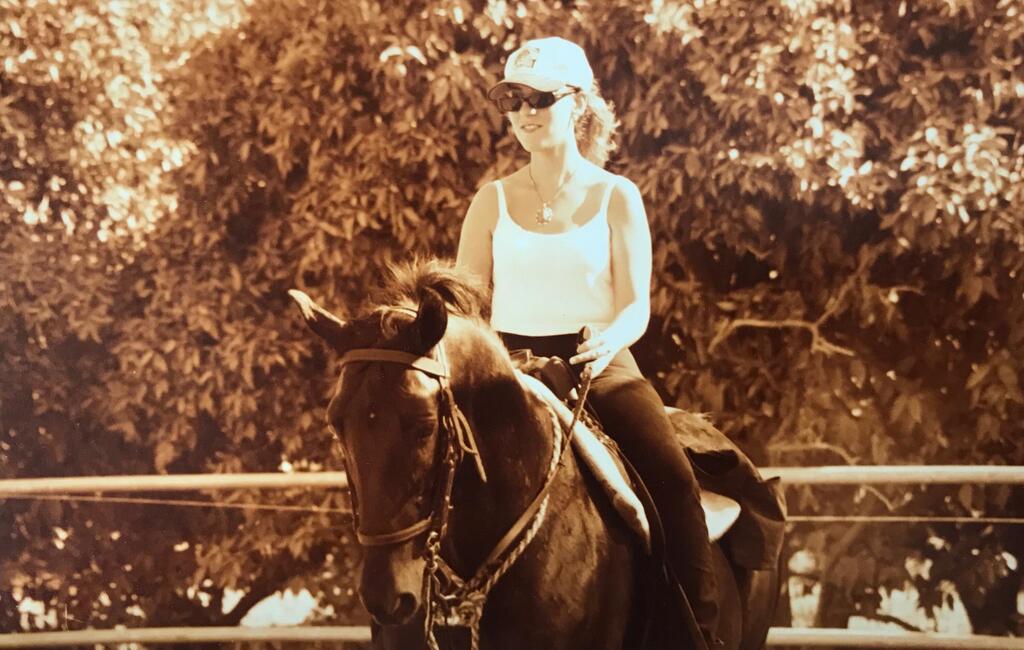

“I looked up the lyrics, and they led me to a book about a horse named Hosanna who makes people better. Suddenly, I saw myself in my mind’s eye riding my brother’s horse into the sunset — and I understood: that’s where I need to go back to. I enrolled in a three-year program for equine-assisted therapy. My family supported me and said, ‘Focus only on this.’ As part of the studies, we were also treated ourselves — with the help of horses.”

'The horses saved my life'

Her trauma erupted again when she began formal training in equine therapy. “I had a full-blown neurotic episode,” she says. “It wasn’t a short panic attack — it lasted three days. I couldn’t eat, drink or sleep. My body shut down.” After being admitted to a psychiatric emergency room, she recalls the doctor’s words: “‘You have to stop drinking and smoking, and you have to treat yourself.’ Luckily, I was already in the equine therapy program — that’s what saved my life. The trauma resurfaced because we started touching the truth, with and without the horses, reaching places buried for years. But this time, I wasn’t alone.”

Ben-Gaon completed her studies, and stability slowly returned. “That’s when I met my husband,” she says. “I was managing the school’s ranch, and life started to move forward. We married quickly, I got pregnant, and I realized I had to pause — you can’t chase horses around an arena with a big belly,” she laughs.

She focused on building a calmer, healthier life. “I had my daughter Ela, then Ofir. I knew I wanted to go back to working with horses — I just didn’t know how. I had a therapy certificate, but I knew the riding wasn’t the core of it. I kept asking myself: what happened in that ranch back then, when I didn’t even get on the horse but still felt healed? What was that connection that brought me back to life?”

That question became her calling. “I went back to study and refine my methods,” she says. “Gradually I began to understand the depth of the human-horse bond — what it awakens in me, and how it helps the people who come to me for help.”

From that realization, the Gallop Center for Equine-Assisted Rehabilitation was born. “At first, it wasn’t even therapy — more like communication training, helping people reconnect with themselves,” she explains. “I kept studying, mostly from international sources. In Israel, there was no one teaching this kind of work from the ground, without riding. So I read research from abroad, took online courses, watched practitioners, and applied it myself. I learned what I had felt from the beginning — that healing doesn’t come from control, but from presence.”

Closing the circle: healing others through horses

Years after discovering by chance the healing power of horses, Ben-Gaon found herself back in the same arena — this time not as a patient seeking comfort, but as a therapist offering it to others. The full circle moment came, as so many things do in life, by accident.

“A man named Amit, a combat soldier from Operation Defensive Shield, came to me for treatment,” she recalls. “He was a PTSD sufferer who hadn’t left his house in almost a decade. He couldn’t work, couldn’t maintain relationships, had no social life. When he arrived at the ranch, he couldn’t stop crying. We sat for hours — talking, laughing, crying. The horses came and went, approaching and stepping back. Each time he reached out to them, something inside him opened a little more.

"For me, it was like reliving my own story — only now I was on the other side. I was the therapist. And I realized I had to understand what was really happening — in the body, not just the mind. So I studied Somatic Experiencing (SE), a trauma-healing approach through body awareness. That was the missing piece. Suddenly, everything connected — my childhood, the accident, the horses, the soldiers who come to me.”

Word of her work spread quickly. “Through my cousin, I met the head of the Duvdevan veterans’ association and the Baruch Scheinberg Foundation for Soldiers’ Independence,” she says. “He came to the ranch and started sending me people.”

That’s how her first therapy group was born — made up of Duvdevan commandos, and even a former prisoner of war from the Yom Kippur War, Nathan Margalit. “It was a meeting of trauma across generations,” she says. “And I realized how similar the pain is, regardless of age or war. Nathan and I had a special bond. He helped me understand why I connect so deeply with soldiers — because I grew up with it. I recognized their symptoms because I’d seen them at home. I myself have a recognized PTSD disability — 42 percent. I know what it’s like to be the daughter of a traumatized veteran, and how that looks inside a family.”

Since then, after hundreds of sessions with soldiers, wounded veterans and trauma survivors — and now with the seventh cycle of her rehabilitation program Hero to Hero underway — Ben-Gaon has witnessed firsthand what science is only beginning to grasp: how contact between a human and a horse can alter states of consciousness, calm an overactive nervous system and restore a basic sense of safety in one’s own body.

'It’s not magic — it’s biology'

“This isn’t magic,” she stresses. “It’s pure biology. We’re mammals. We function on the same system, and mammals live in herds or communities. Like us, horses rely on what’s called the ‘social engagement system’ — we regulate each other emotionally, depend on each other for survival, for safety.”

“The horse’s heart is five or six times larger than ours,” she continues. “They’re naturally calm and can quickly regulate themselves after fear or panic. The stronger their heart impulses, the more they help us synchronize into cardiac coherence when we’re anxious.”

She sees the physical effect week after week. “When someone walks into the arena full of stress or anxiety, within 10 to 15 minutes — as long as the horses are calm — their body calms, their pulse and blood pressure drop. It’s been measured. Just this week, a police officer came in — since the war his smartwatch showed constant high pulse. During the session, his heart rate dropped to 50–56. He said, ‘That hasn’t happened in two years.’”

But not everything is physiological. The horse, she says, also speaks to something ancient in the human psyche. “Carl Jung called them archetypes — collective symbols shared by all humanity, across cultures and time. If you ask someone from the Amazon or from Wall Street, ‘What does a horse mean to you?’ they’ll give the same answer: love, nobility, power, freedom. That’s why seeing a horse triggers something deep within us. Jung said the horse represents our primal passions — the wild emotions we’ve been taught to repress, the part of us that wants to break free.”

Since the war began, Ben-Gaon’s Gallop Center has become a refuge — a place for Israelis to breathe. As an entire nation copes with the emotional shock of October 7, she sees the new face of Israeli trauma up close: soldiers returning from Gaza’s tunnels, survivors of the Re’im festival, volunteers who witnessed horrors firsthand. They all come to her.

Next week, Ben-Gaon will take part in the SPIRIT Festival for Spiritual Cinema at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque (Nov. 12–15), where the film Healing the Heart — about equine-assisted therapy and the profound human–horse connection — will be screened. Afterward, she plans to share her own story and professional insights.

“This film is so important — not just here in Israel but globally,” she says. “People think equine therapy means ‘therapeutic riding for kids with special needs.’ I’m fighting to show that horses aren’t just for children, and it’s not just about riding — it’s about connection from the ground. That’s where the real healing happens. This film finally gives that process a name — and the recognition it deserves.”