Aging does not happen overnight, nor does it follow a single clock. Some people continue to function, think and feel young well into their 70s and 80s, while others develop chronic illnesses already in midlife.

For years, scientists have been trying to understand what distinguishes aging marked by a sharp decline in health from slower, more balanced aging that allows the body to keep repairing itself, protecting vital organs and coping with the damage of time. A new study from Bar-Ilan University now offers a rare glimpse into one mechanism that may help explain that difference.

3 View gallery

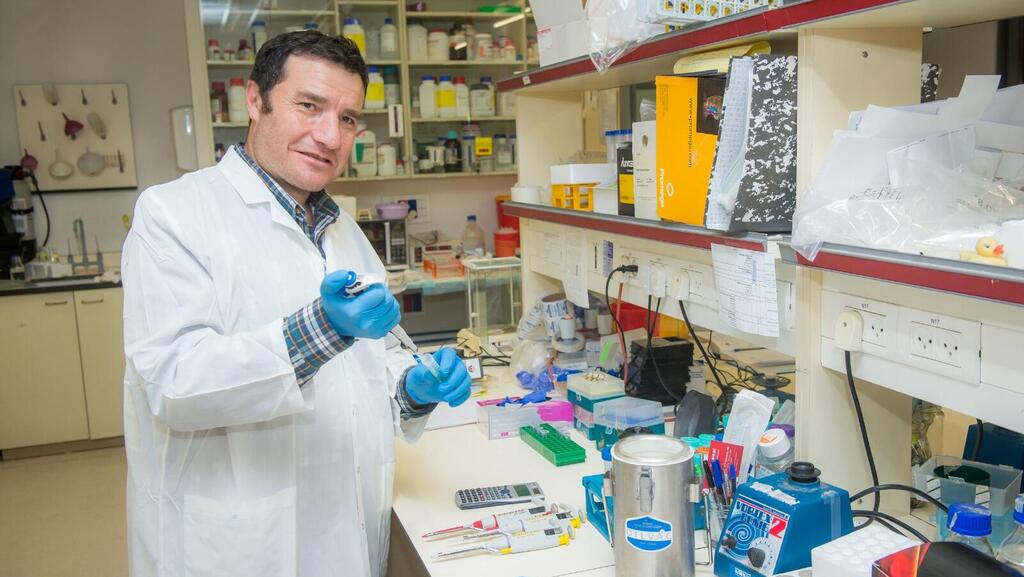

'Evidence points to the role of this protein as a key factor in aging processes'

(Photo: Shutterstock)

The study, published in the scientific journal PNAS, found that a protein called Sirt6 plays a central role in maintaining the balance of a key molecule in the body: hydrogen sulfide gas (H₂S). The research was led by Prof. Haim Cohen and doctoral student Noga Touitou of the Segol Center for Healthy Human Aging at Bar-Ilan University. According to their findings, Sirt6’s ability to precisely regulate levels of the gas, which is essential for wound healing, heart health and cognitive function, may be one of the keys to healthy aging and to slowing processes associated with old age. The next challenge will be moving from animal testing to applied fields such as drug development for humans.

“Healthy aging, in other words, is the postponement of age-related diseases and the ability to remain active in old age,” explains Prof. Cohen, a life sciences expert and head of the Segol Center for Healthy Human Aging at Bar-Ilan University. “It is expressed in the fact that a person is less sick and more active,” he says.

Cohen notes that the steady rise in human life expectancy is accompanied by a troubling trend: an even greater increase in the proportion of people suffering from age-related diseases. “This is a wide spectrum of illnesses. It includes cancer, diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s and especially metabolic and inflammatory diseases,” he says.

“Such diseases tend to accompany us from around ages 40 to 50,” Cohen continues. “You see that many people begin to develop metabolic diseases. One of the main examples is diabetes. First and foremost, it is an age-related disease. As a person grows older, they respond less and less well to insulin produced by the body and begin to develop age-related diabetes. This poses a very big challenge: how to overcome these diseases and slow them down, and by doing so, perhaps extend healthy life expectancy. It is a very big challenge.”

To address the gap between longer life and sustained health, Cohen and his team began by trying to understand the biological mechanisms underlying healthy aging. “One of the things we examined was calorie restriction, which is a significant reduction in food intake that leads to an extension of healthy life expectancy,” he explains.

According to Cohen, this mechanism has been studied for years across a wide range of biological systems. “I can do this in the simplest organisms, such as yeast, worms and flies, up to the results we have been seeing in recent years in humans. Through this, it is possible to improve markers of age-related diseases, mainly metabolic diseases, and as a result extend life expectancy. From this principle grew all the diets people are talking about today, intermittent fasting and so on. From there, the starting point was that if we could find key players that drive the processes of calorie restriction in model organisms, they would also be meaningful for healthy aging in humans.”

Based on that premise, the current study began. “We isolated a protein called Sirt6,” Cohen says. “It is a key player in extending healthy lifespan and, in fact, mediates the effect of calorie restriction. We have already shown in the past that if you overexpress it in model animals, you extend their healthy lifespan by an average of 30 percent, and some lived 50 percent longer,” he emphasizes. “They have far fewer tumors, they are protected from obesity and from all the damage associated with obesity. Other studies have shown this protein’s involvement in preventing Alzheimer’s,” Cohen continues. “It is involved in many things. The totality of the evidence points to its role as a key factor in aging processes.”

The journey to the aging mechanism

At this stage, the research moved from the general question of healthy lifespan to a precise investigation of the protein’s actual activity. In the current study, doctoral student Noga Touitou led the most basic question: what does Sirt6 actually do, and which processes does it act on in the body?

“The Sirt6 protein is like a tool,” Cohen explains. “Most proteins are machines; they know how to do something. The question was who it works on, which materials it uses to carry out its action.”

The first stage involved broad mapping of the protein’s points of activity. “She identified many sites where it operates, but when we looked more deeply, we saw that one of the things that stood out was a pathway called One Carbon. This is a very important pathway in our body. Why did it catch the eye? Because it produces a gas called H₂S,” Cohen says. “This is an unusual molecule: surprisingly, if you have too much of it, you die, but you must keep it at a certain level. And if you raise it slightly, you get the effects of calorie restriction. We hypothesized that a large part of Sirt6’s effect might be related to this.”

Suddenly, we discovered the range of Sirt6’s capabilities. This opens the possibility of a more precise approach in which we can develop personalized medicine. The second thing it opened up is that it gave us an explanation of how Sirt6 works. The big step now is to develop drugs that enhance Sirt6, in order to achieve healthy life extension in humans.

Touitou’s tests strengthened that hypothesis. “She showed that Sirt6 keeps the gas within the correct range,” Cohen explains. “With age, our ability to produce it decreases significantly, and Sirt6 keeps it in the right range, raising it a bit while preventing a large increase. We called it in the paper ‘one foot on the brake, one foot on the gas’ — it keeps it in the correct domain where you get life extension. That closed the circle for us,” Cohen sums up. “We knew there was the phenomenon of calorie restriction, we knew Sirt6 played a role there, and now we found the missing component: the gas through which it extends life.”

According to Cohen, several possible strategies now open up. “You can simply increase H₂S levels, or you can activate Sirt6 itself.” The difference, he stresses, is significant. “If we develop drugs that only slightly raise the level of the gas, we will manage to improve life expectancy somewhat. But if we develop drugs that increase the activity of Sirt6, we can gain a range of benefits. Sirt6 takes care of DNA repair, it is active as an anti-cancer factor through a completely different mechanism. Based on previous research, the company Sirtlab was established, which is developing drugs that activate Sirt6 with the aim of extending healthy life expectancy in humans.”

Cohen says the study’s findings have two main implications. The first concerns a broader understanding of the protein’s activity. “The study opened up several things,” he says. “Suddenly, we discovered the range of Sirt6’s capabilities. This opens the possibility of a more precise approach in which we can develop personalized medicine. The second thing it opened up is that it gave us an explanation of how Sirt6 works,” he says. Based on that understanding, he points to the next step in the research. “The big step now is to develop drugs that enhance Sirt6, in order to achieve healthy life extension in humans.”

The study was conducted in collaboration with the research group of Prof. Rafael de Cabo of the U.S. National Institute on Aging, with support from the Segol Network, the U.S.-Israel Binational Science Foundation, the Israel Science Foundation and Israel’s Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology.