The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a groundbreaking clinical trial to test the use of a genetically modified pig liver as a temporary external treatment for patients suffering from acute liver failure, the Associated Press reported.

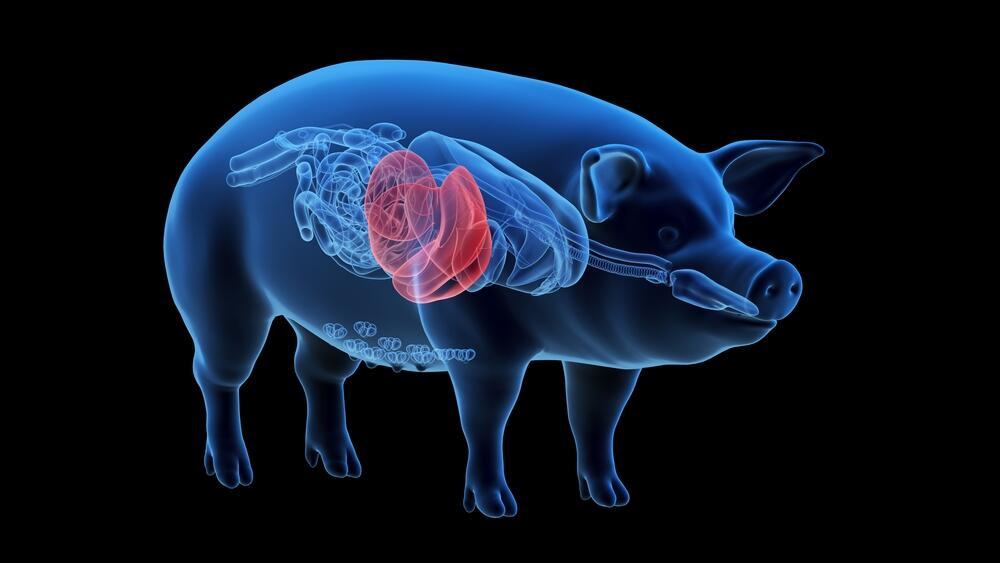

In the novel approach, the pig liver will not be transplanted into the patient’s body. Instead, it will be connected externally and function as a temporary blood filtration system—similar in concept to dialysis—designed to give the patient’s own liver time to rest and potentially recover.

Each year, about 35,000 Americans are hospitalized due to sudden liver failure. Treatment options are limited, and mortality rates in such cases can reach up to 50%. Many patients are not eligible for liver transplants or fail to receive an organ in time.

A broader trend: pig organs in human treatment

The trial, expected to begin this spring, is led by Massachusetts-based biotech firm eGenesis in collaboration with UK-based OrganOx. The method differs from previous efforts in xenotransplantation—transplanting animal organs into humans—by using the pig liver outside the body rather than implanting it.

While the study does not involve actual transplantation, it reflects a growing global trend of research into genetically modified pig organs as a solution to human organ shortages. Since 2022, experimental transplants of pig hearts and kidneys into living human patients have been conducted in the U.S. and China with mixed outcomes. The pig heart transplants failed to provide long-term survival, but two kidney transplants in the U.S. were deemed successful, with patients surviving several months with the organs.

In another milestone, Chinese researchers last year successfully transplanted a genetically engineered pig liver into a brain-dead human patient. The organ functioned for ten days, maintaining normal blood flow, producing bile and albumin, and showing no signs of acute immune rejection.

Pig liver as temporary lifeline

While the human liver is the only organ in the body capable of regeneration, the key question behind a new FDA-approved trial is whether passing a patient’s blood through a genetically engineered pig liver for several days can buy enough time for recovery.

eGenesis CEO Mike Curtis told the Associated Press that prior experiments on four deceased bodies showed that a gene-edited pig liver was able to support partial human liver function for two to three days. He described the method as a potential “bridge” treatment for critically ill patients.

The clinical trial, expected to begin this spring, will include up to 20 patients in intensive care units who are not eligible for liver transplants. The procedure involves a device developed by British firm OrganOx—originally designed to preserve human donor livers—being used to circulate the patient’s blood through the pig liver outside the body.

A new step in using genetically modified pig organs

The trial marks another step in the growing field of xenotransplantation—using genetically engineered pig organs to save human lives. Pig kidneys developed by eGenesis and United Therapeutics have already been used in experimental transplants in humans. Now, researchers are testing whether pig livers can provide temporary life support for patients with acute liver failure.

“This is an area where people are dying while waiting for a liver transplant,” said Dr. Helena Katchman, head of the Liver Unit at Tel Aviv Medical Center and chair of the Israel Society for Liver Research. “The shortage of donor livers is a critical problem in Israel and globally. For decades, scientists have worked on using animal organs—especially pig organs—as a solution.”

Dr. Helena Katchman Photo: Courtesy

Dr. Helena Katchman Photo: CourtesyShe emphasized the challenges: “These transplants face serious issues, especially strong immune rejection due to genetic differences, and the risk of infections carried by pigs. That’s why the U.S. spent years developing genetically engineered pigs bred in sterile environments to reduce these risks.”

Dr. Katchman noted that these are typically smaller pigs, bred to be more size-compatible with humans, with genetic modifications designed to reduce rejection. In recent years, pig organ transplants have been performed on brain-dead patients or patients with advanced terminal conditions. “There’s real hope here, but also a lot of hurdles still to overcome.”

What makes the current approach different, she said, is that it does not involve permanent transplantation. “This is a ‘bridge treatment’—for someone with acute liver failure, usually from drug toxicity or a severe viral infection. In many of these cases, the liver is otherwise healthy and can regenerate if given time. The goal is to help the patient survive the acute phase until the liver recovers—or until a donor organ becomes available.”

In the past, devices mimicking liver dialysis were used, she added, but “in recent years, most of the world abandoned those methods due to limited effectiveness.” The new trial, she explained, uses a genetically engineered pig liver as a kind of “biological dialysis,” filtering the patient’s blood and buying valuable time.

“This is a significant and necessary step forward in addressing a critical medical need that hasn’t had an adequate solution,” she concluded. “Widespread clinical use is still a long way off and will require further research and trials—but it’s a promising step in the fight against organ shortages, especially for patients waiting for transplants.”

Still, she added, “The most important message is prevention. Protect your liver and avoid the factors that can damage it in the first place.”