“And God said, ‘Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.’”

Biblical cosmology—like many ancient mythologies—described the firmament as a vast, solid dome created by God during the act of creation in Genesis. Its purpose was to divide the primordial waters into two parts—above and below—and to make way for dry land to emerge. The idea of a solid sky was widespread in ancient cultures. For example, the Venda people of South Africa believed the stars were either hanging from the dome of the firmament or were holes in it through which the sun shines at night. In ancient Egypt, the stars were seen as part of the goddess Nut, whose star-covered body arched over the earth.

A central assumption shared by all these worldviews was that Earth occupies the center of the universe. This idea, known as the geocentric model, aligns closely with everyday human perception: the ground beneath us feels solid, stable, and unmoving. From almost anywhere on Earth, the sun appears to rise and set as it moves across the sky each day, while the moon and planets seem to orbit around us.

Ancient Greek philosophers largely supported the geocentric view. Although Aristarchus of Samos proposed a heliocentric model in the 3rd century BCE, placing the sun at the center, the prevailing view was that of Aristotle, who envisioned the universe as a series of nested, hollow spheres with Earth at the center. According to him, the moon, sun, planets, and stars were fixed to these spheres, and beyond them was the Primum Mobile—the "first mover"—which rotated continuously, setting all the inner spheres in motion. Ptolemy, a Greek astronomer based in Alexandria, later refined Aristotle’s model, adding complex adjustments that allowed for fairly accurate predictions of celestial positions. This geocentric worldview dominated human understanding of the cosmos for many centuries.

Nearly 1,700 years passed before significant progress was made in challenging the long-standing geocentric view. It was the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus who reintroduced the heliocentric model, placing the sun at the center of the solar system. Others built upon his work to further develop the model and address the questions it raised. Tycho Brahe carried out the most precise astronomical observations of his time, Johannes Kepler formulated the laws of planetary motion, demonstrating that planets move in elliptical orbits, and Galileo Galilei published his telescopic observations of Jupiter’s moons in Italian rather than Latin, helping to make the scientific debate accessible to the broader public. By the mid-17th century, after more than a millennium, the heliocentric model was finally accepted as the accurate scientific explanation of the solar system. Today, it is part of a broader understanding, in which the sun itself orbits the center of the Milky Way galaxy, just one among billions of galaxies in the universe.

Still, even today, some people continue to support the geocentric model. One such example is Robert Sungenis, an apologist associated with the Christian apologetics movement, who authored a book titled Galileo Was Wrong! In it, he asserts that the Bible and the New Testament are humanity’s sole sources of truth, and that any information contradicting them - including modern science - must be false. To bolster his argument, he invokes contemporary physical theories, including Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, in an effort to present geocentrism as scientifically legitimate.

The geocentric model also appears in the claims of certain rabbis and religious returnees who assert that everything in the Jewish scriptures is absolute truth. They, too, employ scientific language to support positions that contradict well-established scientific understanding—providing a clear example of pseudoscience: ideas that claim to be scientific but fundamentally lack scientific validity.

What makes a theory pseudoscientific?

How can you recognize pseudoscience? A key warning sign is that it sounds scientific but lacks real scientific support—if any at all. Words like “quantum” or “energy” are often used to create an illusion of credibility, even though they have no meaningful relevance in the context where they’re applied. Another hallmark of pseudoscience is the false claim of endorsement by respected scientists or institutions. Such assertions are usually unfounded and misrepresent the actual scientific consensus.

When examining the details, it often becomes clear that the proposed explanation is based on cherry-picking—the deliberate exclusion of data that does not support the hypothesis, while selectively presenting only the information that does. Unlike genuine scientific practice, which strives to consider and address all available evidence—including data that may challenge or contradict the hypothesis—pseudoscience ignores anything that might contradict the preferred narrative. Another common tactic is the distortion of scientific studies: quoting legitimate scientific research, but twisting its meaning to falsely suggest support for the theory. This is typically done by taking statements out of context, misinterpreting the original findings, and creating misleading logical connections between unrelated phenomena. In doing so, pseudoscientific claims may superficially appear grounded in science, but they fundamentally misrepresent the original sources.

A central characteristic of pseudoscientific theories is their blatant disregard for the scientific method. Time and again, they reject core scientific practices such as peer review, controlled experimentation, and the principle of empirical falsifiability - the idea that a claim must be testable and capable of being proven false. This rejection is often accompanied by blatant accusations that the “scientific establishment” is engaged in a conspiracy to suppress the truth.

Pseudoscience often emerges from the realm of fringe theories—innovative hypotheses and ideas that exist at the outer edges of scientific reasoning. Sometimes these are provocative concepts that have not yet been thoroughly examined, and other times they are ideas that have been overlooked or rejected by the scientific community. However, when such fringe theories abandon the tools of scientific investigation—such as empirical testing, falsifiability, and peer review—they risk crossing the line into pseudoscience: cloaked in scientific language but ultimately rooted in belief, anecdote, deliberate misrepresentation or deception.

Of course, not all fringe theories are pseudoscientific. History offers examples of ideas initially rejected by the scientific establishment of their time due to lack of solid evidence or excessive conservatism, but were later validated. For example, Alfred Wegener’s theory of continental drift was rejected for decades before becoming the foundation of modern plate tectonics, which now plays a central role in our understanding of Earth’s geology. Also well known is Dan Shechtman’s discovery of quasicrystals, which for many years was met with skepticism, but ultimately earned him a Nobel Prize. The difference? These theories were supported by consistent, reproducible data and stood up to rigorous scientific scrutiny. Most pseudoscientific theories, by contrast, lack a real scientific basis—and are rightly dismissed.

The Anunnaki story

In the field of astronomy, some pseudoscientific theories draw partially from ancient myths. One such theory claims that the gods of ancient Sumerian culture were actually extraterrestrials from a planet called Nibiru—described as a “12th planet” in the solar system, which allegedly orbits the Sun once every 3,600 years in an extremely elongated elliptical path. According to the theory’s originator, American author Zecharia Sitchin, these ancient astronauts, known as the Anunnaki, arrived on Earth approximately 400,000 years ago to mine gold needed to restore their home planet’s atmosphere.

Sitchin claimed that during their stay on Earth, the Anunnaki created the human species through genetic engineering—allegedly by combining their own DNA with the genetic material of Homo erectus, with the goal of producing a new species to serve as slaves in their gold mines. He further asserted that a conflict between rival factions of the Anunnaki escalated into the use of nuclear weapons—an event that can supposedly be traced in ancient Sumerian poems describing the destruction of the city of Ur by a “bad wind,” as well as in the biblical account of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. According to Sitchin, the Anunnaki eventually departed Earth about 4,000 years ago, following the catastrophe of the Great Flood.

Sitchin’s highly narrative theory followed in the footsteps of earlier ideas suggesting that human civilization originated through visits by ancient extraterrestrials. Proponents of these ancient astronaut theories—such as Erich von Däniken, author of Chariots of the Gods—have argued that references to ancient alien beings can be found in the Bible. As supposed evidence, they often point to the Nephilim mentioned in Genesis, Ezekiel’s vision of celestial chariots, and the mysterious effects attributed to the Ark of the Covenant.

The Anunnaki theory is a clear example of pseudoscience. Scholars of the Sumerian language have shown that Sitchin misinterpreted key terms and manipulated translations to fit a narrative he had constructed. He also took quotes and passages out of context, creating a story that does not appear in the original texts. In reality, there is no archaeological evidence to support the existence of advanced technology in ancient times. If such a technologically advanced culture had existed, we would expect to find clear traces, such as advanced metal tools, artifacts made of materials unknown at the time, or even remnants of devices or spacecraft.

In fact, all available evidence supports the gradual evolutionary development of humanity. Sitchin claimed that a genetic alteration around 300,000 years ago suddenly produced modern humans, but genetic evidence shows a continuous evolutionary timeline, with no indication of external intervention or the introduction of foreign genetic material. Moreover, the existence of a planet like Nibiru, said to orbit the Sun every 3,600 years, is not supported by any astronomical data. A planet of that size within our solar system would necessarily have noticeable gravitational effects on the orbits of known planets and would be visible through modern observation techniques.

Sitchin’s alien theory generated much interest, especially in popular culture and science fiction. Its greatest exposure came through the television series Ancient Aliens, broadcast among others on the History Channel via the cable network HOT in Israel. This connection is particularly puzzling as it presents pseudoscience on a channel that is supposed to promote evidence-based historical knowledge. Today, there are groups of believers and even esoteric religions that have incorporated the Anunnaki or similar ancient astronaut ideas into their belief systems. However, most of the public does not take these theories seriously.

Sitchin’s alien theory attracted significant interest, particularly within popular culture and science fiction. It gained its widest exposure through the television series Ancient Aliens, broadcast primarily on various history channels. This is especially puzzling, as such platforms are generally expected to promote evidence-based historical content, yet they provided a stage for pseudoscientific claims. Today, various groups of believers—and even some esoteric religions—have incorporated the Anunnaki or similar ancient astronaut concepts into their belief systems. Nevertheless, the majority of the public regards these theories with skepticism and does not take them seriously.

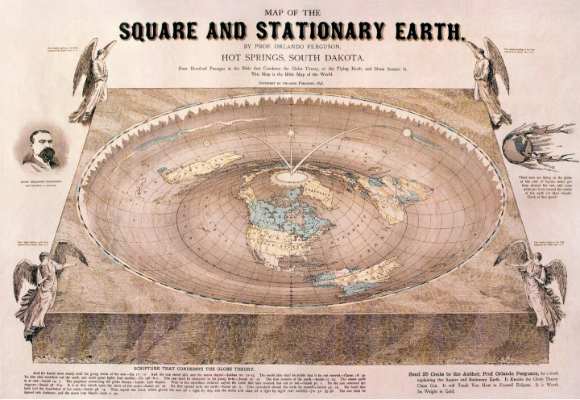

Flat Earth

The geocentric model persisted for centuries, partly because it successfully explained many observable phenomena. It was ultimately replaced when more accurate models to explain those phenomena emerged. In that sense, modern supporters of the geocentric model might seem more rational than those who believe the Earth is flat. According to flat Earth theory, our planet is a flat, circular disk, bordered on all sides by a massive wall of ice—Antarctica—which holds the oceans in and prevents them from spilling over the edge. Believers often claim that the sun moves in a circular path above the disk, orbiting the North Pole at the center, and that its light behaves like a spotlight. They also reject the concept of gravity, proposing alternative explanations—for example, that the flat Earth is accelerating upward at a constant rate, creating the illusion of gravitational force.

This theory has ancient roots. In early cultures—including those of ancient Greece, China, Mesopotamia (including early Judaism), India, and the Norse societies of Northern Europe—the world was commonly envisioned as flat, often with a dome-like sky arching above it. However, even during the era when Aristotle’s geocentric model prevailed, there was little serious debate about the Earth's spherical shape, as the evidence was both observable and verifiable. Remarkably, as early as the third century BCE, Eratosthenes calculated the Earth's circumference with impressive accuracy using simple observations and basic geometry.

The rise of the internet and social media has significantly expanded the reach of flat-Earth beliefs - a view that, since the mid-19th century, had been held only by a small fringe. Recent surveys reveal troubling trends. In the United States, a 2018 YouGov survey found that around 2% of Americans firmly believe the Earth is flat, while an additional 5% expressed some doubt about its roundness. A 2021 POLES survey, conducted by the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School, reported that roughly one in ten U.S. adults either accept or are open to the idea that the Earth is flat. In the United Kingdom, a 2019 YouGov poll found that about 3% of respondents said the theory was “probably” or “definitely” true, with another 4% unsure. A survey in Brazil suggested that as much as 20% of the country’s population believes in a flat Earth.

Beyond the broad and well-established body of scientific evidence disproving the flat Earth theory, the model fails to account for numerous observable phenomena. For example, the curvature of the horizon is clearly visible from high altitudes, and photographs taken from space or the upper atmosphere unmistakably show the Earth’s curved surface. Similarly, anyone who has watched a large ship sailing toward the horizon can observe that its lower portion disappears from view first, while the upper decks remain visible for longer—clear, everyday evidence of the Earth’s curvature.

The flat Earth theory also fails to consistently explain key phenomena such as seasonal variations across different regions and the contrasting appearance of the night sky in the northern and southern hemispheres. On a flat Earth, all observers would be expected to see the same stars regardless of location. In reality, however, entirely different constellations are visible in the southern hemisphere compared to the northern one. This is clear evidence that observers are oriented in different directions on a curved, spherical surface. Flat Earth proponents attempt to address each of these inconsistencies with separate, often contradictory explanations, even though the spherical Earth model accounts for all of them with a single, coherent framework.

Over the years, flat Earth believers have conducted several experiments in an effort to prove their claims. Time and again, these experiments have failed—often producing results that directly contradict their expectations. YouTuber Jeran Campanella, a prominent figure among flat Earth content creators, participated in several of these experiments. One notable example was the “horizontal beam” experiment, conducted in 2018 and featured in the documentary Behind the Curve. In this experiment, Campanella and his partners positioned two boards with holes at a height of five meters and spaced fifteen meters apart, aiming to shine a beam of light straight through both. However, the film shows that the beam was not visible to the camera on the other side until the light source was raised—directly confirming Earth’s curvature. Campanella’s reaction was simply, “Interesting… very interesting.”

In 2024, Campanella participated in another high-profile experiment, known as the “final experiment,” conducted in Antarctica. An eight-person expedition—including four flat Earthers—traveled to the frozen southern continent to observe the phenomenon known as the midnight sun, which occurs during the southern hemisphere’s summer solstice, when the sun remains visible for a full 24 hours near the pole. This phenomenon is entirely incompatible with the flat Earth model. According to that model, the sun is a fiery sphere that moves in a circular path above the flat Earth, illuminating different areas at different times. Antarctica, they claim, forms a massive ice wall encircling the entire world, and given its position, the sun could not be visible there for 24 continuous hours. Yet upon arriving, the group observed exactly that: the sun did not set for a full day. Campanella was filmed saying, “Sometimes people discover the mistakes they made in their lives.”

Upon returning from Antarctica, the expedition members publicly shared their observations. However, their evidence failed to convince the flat Earth community. Its members dismissed it as a hoax, claiming the footage had been staged in a studio using green screens, and arguing that the participants—who had until recently been outspoken flat Earth advocates—had become part of a vast conspiracy, with unclear motives, aimed at promoting the spherical Earth model.

Between pseudoscience and conspiracy theories

Why do people believe in disproven theories like the flat Earth—ideas that contradict both everyday experience and the extensive scientific knowledge we have about the world? Researchers who study the flat Earth movement and its followers describe a mindset rooted in conspiratorial thinking: a psychological tendency in which individuals lose the ability to judge when and whom to trust, and when skepticism is appropriate. The rise of the internet and social media has amplified this phenomenon by providing platforms where misinformation can spread rapidly and like-minded communities can easily form. Without the traditional gatekeepers who once filtered information for accuracy before it reached the public, the unchecked spread of such theories has accelerated dramatically.

Flat Earth believers reject all images of Earth from space as fabrications. They also question the authority of scientists and scientific organizations like NASA, which they view as central players in a global conspiracy to conceal the “truth” about Earth’s supposed flatness. According to this view, even rival or hostile space agencies and governments are inexplicably cooperating in a unified effort to conceal this truth.

In their version of reality, fundamental scientific concepts such as gravity and the Earth's circumference are considered inventions, and technological achievements like flights, satellites, and space missions are staged hoaxes designed to mislead. Explanations for the alleged deception vary, including motives such as controlling the masses, securing political power or funding—like NASA’s multi-billion-dollar budget—or even a conspiracy to suppress the truth about God’s existence, since the Bible never explicitly states that the world is a sphere.

While there is often overlap between pseudoscience and conspiracy theories, conspiracy thinking has distinct features. These theories typically center on the belief that an all-powerful, malevolent group is orchestrating a grand deception. This group—comprising individuals and organizations with seemingly extraordinary capabilities—is believed to operate in a highly coordinated and meticulous way to harm, mislead the public, and conceal the truth. Such theories often assume an implausible level of cooperation, involving hundreds of thousands of people who all supposedly maintain absolute loyalty to the conspiracy and uphold strict secrecy.

Another hallmark of conspiratorial thinking is the belief that nothing is as it seems, and that no person or source can be trusted—except, of course, those who claim to have “uncovered” the conspiracy and now promote their version of the truth. This mindset reflects a form of paranoid thinking, where any evidence that contradicts the theory is automatically dismissed as part of the conspiracy itself. As a result, the theory becomes self-reinforcing and virtually immune to criticism.

The irony is that the more deeply someone believes in conspiracy theories, the more susceptible they become to actual deception, as their critical thinking skills are gradually eroded. Accepting far-fetched claims without examination or verification does not reflect independent thinking, but rather a surrender to the cognitive biases and flawed perceptions to which humans are naturally prone.

The challenge of critical thinking in the information age

We live in an age overwhelmed by a flood of conspiracy theories, many of them baseless, circulating alongside the exposure of real conspiracies—instances of corruption and fraud involving powerful entities. The ability to distinguish truth from falsehood and baseless conspiracy theories has never been more essential - or more challenging. Paradoxically, despite the unprecedented availability and accessibility of information, it is often harder than ever to separate fact from fiction. In this landscape, we must remain cautious and vigilant, remembering that not everything that sounds scientific truly is. Developing strong critical thinking skills is essential to avoid being misled and to steer clear of the wrong paths.