Could a technology that transformed the treatment of blood cancer also open a new path in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease? A new study by scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science and Washington University in St. Louis presents the first use of CAR-T technology to treat a neurodegenerative brain disease.

In experiments conducted in mice, researchers recorded a significant reduction in amyloid-beta plaques and markers of brain inflammation, offering a potential new direction as Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases become an expanding global health challenge.

2 View gallery

Researchers recorded a significant drop in amyloid-beta plaques and brain inflammation, pointing to a possible new direction for treating Alzheimer’s

(Photo: Shutterstock)

The researchers say existing treatments, including some approved in recent years, remain limited in their effectiveness, underscoring the urgent need for new therapeutic approaches.

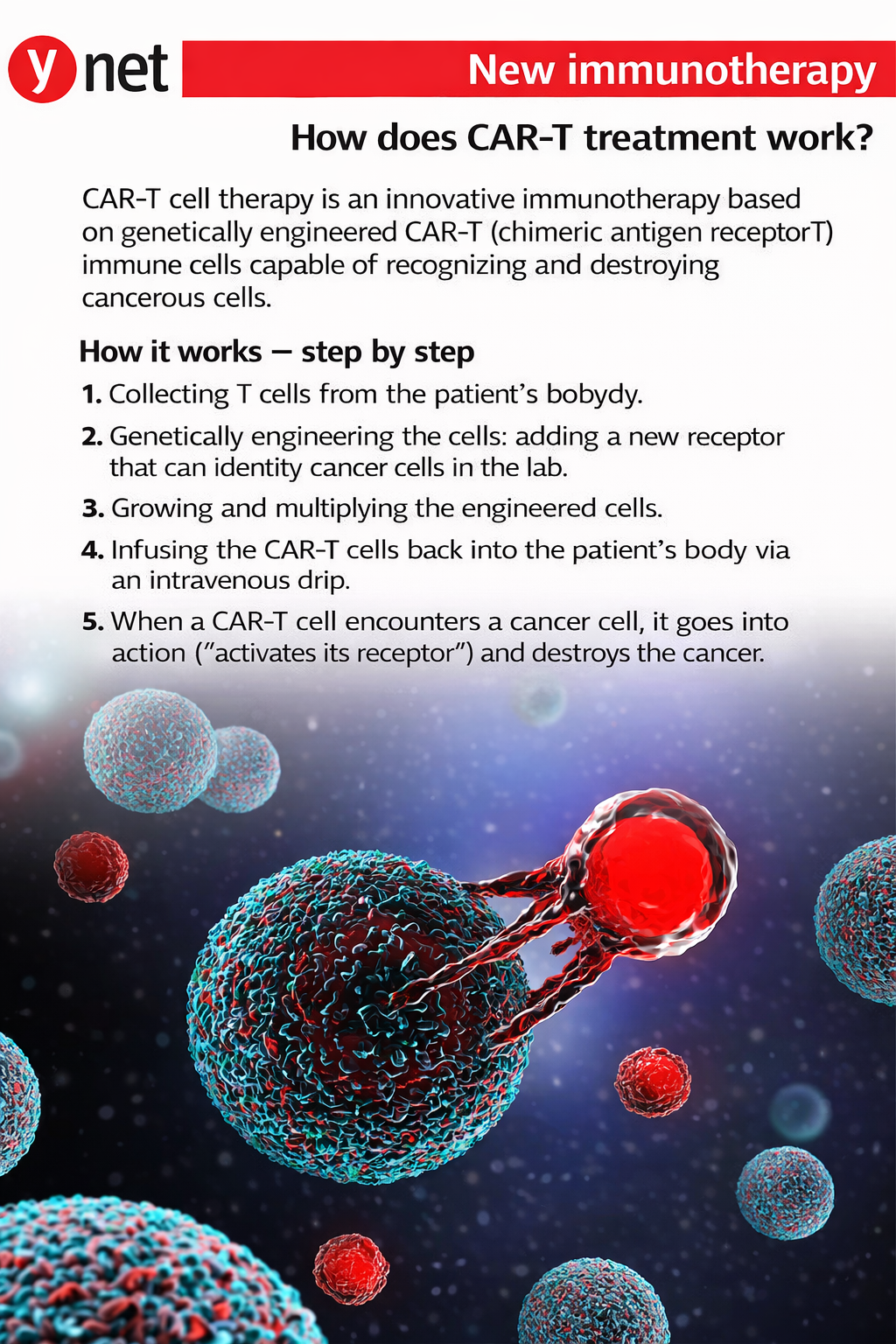

The study was published Monday in the scientific journal PNAS and builds on work pioneered more than three decades ago by Prof. Zelig Eshhar of the Weizmann Institute, who died last year. Eshhar laid the foundation for genetically engineering T cells from the immune system so they can recognize and attack specific targets in the body. The approach, known as CAR-T, has since become one of the most innovative and effective treatments for blood cancers.

The new research marks the first attempt to apply CAR-T technology to Alzheimer’s disease.

The international research team was co-led by Prof. Ido Amit of the Weizmann Institute’s Department of Systems Immunology and Prof. Jonathan Kipnis of Washington University’s School of Medicine in St. Louis. The study was led by postdoctoral researcher Dr. Pavel Boscovich, with contributions from doctoral students Rotem Shlita and Maya Ben Yehuda from Amit’s laboratory.

The researchers extracted T cells from healthy mice and genetically engineered them to recognize amyloid proteins in the brain. The modified cells were then injected into mice that had already developed amyloid-beta plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease.

Following the injections, the mice showed a marked reduction in plaque accumulation, along with decreased indicators of inflammation in brain tissue.

“This study provides the first proof of feasibility for treating neurodegenerative diseases using CAR-T technology,” Kipnis said. “It is an exciting step toward developing new therapies for Alzheimer’s and other diseases, including ALS and Parkinson’s.”

Turning the immune system into a therapeutic tool

Amit explained that one of the central challenges in treating complex diseases such as Alzheimer’s is the difficulty of altering the damaged environment in which the disease develops.

“Even very sophisticated molecules fail to repair that environment, and their activity is limited,” he said.

Unlike conventional drugs that act in a focused, single-target manner, living cells are capable of performing many complex functions simultaneously, Amit said.

“The potential is to take cells that can carry out many actions and use them to change the entire environment,” he said.

Amit added that CAR-T technology has fundamentally reshaped how medicine thinks about drugs.

“People still do not fully appreciate how much this Israeli invention has changed the concept of what a drug looks like,” he said.

Prof. Jonathan Kipnis

Prof. Jonathan KipnisTo date, CAR-T has been used mainly to treat blood cancers, where it has produced dramatic results. Only in the past two years, Amit said, has it become clear that CAR-T is a far broader platform, with potential applications beyond cancer.

In recent years, significant successes have also been reported using CAR-T in autoimmune diseases, including studies in humans rather than only in experimental models. In some cases, patients who had not responded to any other treatment showed rapid improvement after a single CAR-T therapy, including in Israel.

Prof. Ido Amit

Prof. Ido AmitAgainst this backdrop, Amit’s lab decided to explore whether the approach could be applied to Alzheimer’s, a disease for which there is currently no curative treatment.

“We wanted to see whether this technology could influence pathological processes in the brain as well,” he said.

So far, the work has been conducted only in mice, but the results are encouraging. The CAR-T cells reached the brain, carried out beneficial activities and showed signs of slowing disease progression.

The central challenge: safety and brain access

Despite the promising findings, researchers stress that applying the approach in humans remains a distant goal. Amit said the primary challenge at this stage is safety.

“These are immune system cells being introduced into the brain, and we must ensure they do not cause harm,” he said.

One major focus of the research is modifying the cells’ activity so they function as supportive cells rather than destructive ones. Another concern is the risk of damage to brain tissue.

As part of the genetic engineering process, researchers remove traits that could be harmful and give the cells characteristics of supportive cells aimed at helping rebuild neurons. At the same time, they are working to enhance the cells’ ability to release growth factors that could aid brain repair and recovery.

Asked whether the treatment is specific to Alzheimer’s or part of a broader therapeutic platform, Amit pointed to recent breakthroughs using CAR-T in autoimmune diseases, including conditions affecting the nervous system such as multiple sclerosis.

The expansion of CAR-T into additional diseases has generated growing interest, he said, and the current study represents another step toward applying the technology to widespread and currently incurable illnesses such as Alzheimer’s.