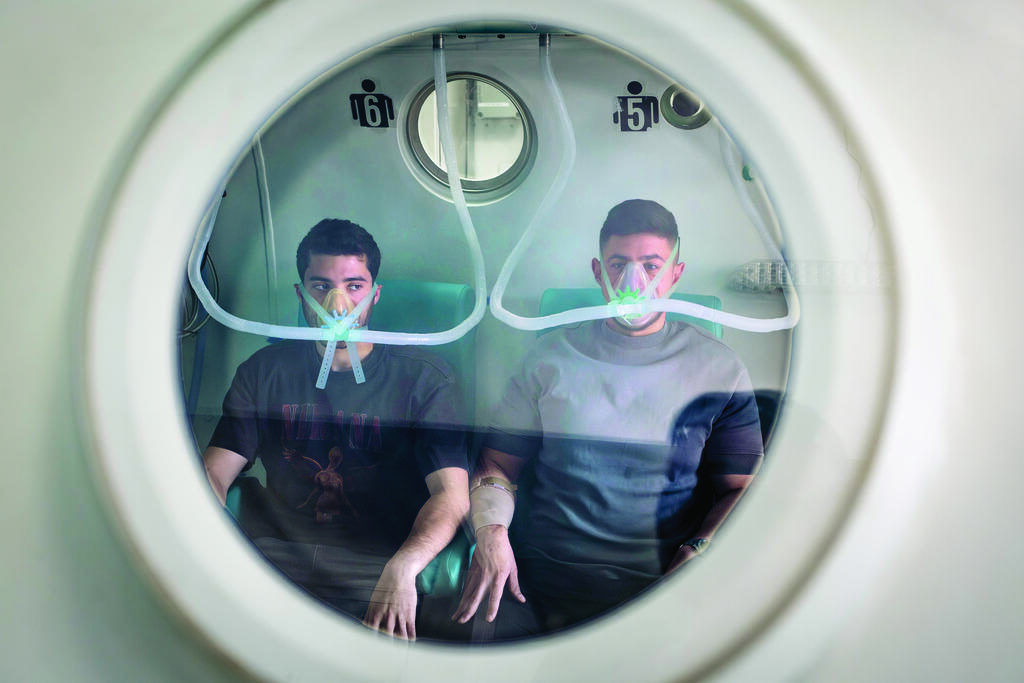

Every day, dozens of wounded soldiers enter the hyperbaric pressure chambers at the Israeli Navy’s Institute for Maritime Medicine in Haifa. Oxygen masks cover their faces, phones are left outside, and for two hours they are cut off from the world.

The institute was originally intended to treat diving injuries. Since October 7, however, it has become a critical rehabilitation hub for fighters injured in combat, including soldiers with severe burns, amputations, blast injuries, and hearing damage. The conditions inside are not easy. It is cold. Pressure builds in the ears. But the benefits go far beyond medicine. “It’s a kind of support group,” says Staff Sgt. M. “We are disconnected from the world in there.”

‘I knew something was terribly wrong’

Staff Sgt. Y., a combat medic in the Border Police, was weeks away from his discharge when an explosive device detonated beneath his armored vehicle during routine activity in the Jenin refugee camp. The incident occurred on January 7, 2024, roughly three months after the war began.

“There were four of us inside the vehicle,” he recalls. “The device contained 50 kilograms of explosives and was buried underground. We never saw it coming.”

From the force of the blast, Sgt. Shi Germai, who was seated next to him, was killed. The two other soldiers were also wounded.

“Shi and I were thrown from the vehicle,” Y. continues. “My helmet shattered, and I was badly injured in my leg and head. I was conscious all the way to Rambam hospital, but I remember almost nothing from the evacuation. Later, a brief image came back to me. I was lying on the ground, looking down and seeing an open fracture. My right leg was severed and twisted from the shin down. I remember thinking, ‘Damn, this is bad.’”

Immediately after waking from surgery, during which blood vessels from his other leg were transplanted and metal plates were inserted for stabilization, Y. was transferred to the hyperbaric chamber at the Institute for Maritime Medicine, located adjacent to the hospital. The goal was to improve blood flow and salvage as much tissue as possible.

“At first, they took me once a day, then twice a day, for two-hour sessions,” he says. “It was difficult. My nose was broken in the blast, and it hurt to wear the oxygen mask. Screens are not allowed inside, so I was lying there helpless, with the medic who supervises the patients. Luckily, he was my age, so we talked. Sometimes we solved crossword puzzles.”

What does it feel like inside the chamber?

“It’s cold. You wear an oxygen mask and can only remove it according to instructions. When the pressure increases, you feel it in your ears, but you can manage it by equalizing. Aside from the boredom, I felt normal.”

Despite all efforts, doctors ultimately had to amputate Y.’s injured leg due to medical complications. Thanks to the hyperbaric treatments, however, the amputation was significantly lower than initially expected, a factor that has a major impact on rehabilitation and mobility.

“In the world of amputations, height is everything,” he says. “Every half-centimeter up or down makes an enormous difference.”

After a lengthy rehabilitation process and being fitted with a prosthetic limb, Y. returned to marathon training, something he did even before his injury.

“The doctors are trying to stop me,” he says with a smile. “They say I put too much pressure on my left leg, which was also injured. Eventually, I will return to the army. For now, I am enjoying life. This injury lets me do what I want. I do not have time to be frustrated.”

From divers to fighters

For decades, the Navy’s Institute for Maritime Medicine in Haifa has been a unique national center for diving medicine, marine physiology, and hyperbaric treatment. Established in the 1970s by pioneering physicians led by Col. (res.) Dr. Yehuda Melamed, it became a cornerstone of Israel’s military medical system and a national center of expertise.

At the heart of the institute are advanced hyperbaric chambers that can treat up to 12 patients simultaneously. They are used for a wide range of conditions, including decompression sickness, embolisms, blast injuries, gas poisoning, and complex tissue damage. Patients breathe oxygen at pressures higher than atmospheric levels, increasing oxygen delivery to tissues and supporting processes such as wound healing, blood vessel growth, and bone regeneration.

The institute is recognized by the Health Ministry as Israel’s national center for diving accident treatment, while also treating civilians and soldiers whose recovery can benefit from hyperbaric therapy. Its research, published in international journals, analyzes decades of data on decompression injuries, ear trauma, and pressure balance in divers, and examines the medical fitness of soldiers operating under extreme environmental stress.

The war dramatically altered the institute’s workload

“Before the war, we mainly treated chronic wounds and pain syndromes,” says Lt. Col. Dr. A., the institute’s commander. “Today, we are one of the three largest hyperbaric medicine centers in Israel, treating soldiers with amputations, orthopedic injuries, and complex trauma. We provide solutions not only related to diving, but to all operational environments, above and below water.”

A critical window for hearing injuries

One of the most significant breakthroughs during the war has been the treatment of hearing damage.

“Already in 2016, we began exploring hyperbaric therapy for acoustic trauma,” says Maj. M., an audiologist who leads the institute’s hearing injury program. “Scientific literature suggested it could be effective for battlefield-related hearing loss.”

In 2019, the institute published Israel’s first treatment protocol for acoustic trauma in hyperbaric chambers. In early 2023, a formal procedure was adopted.

“The critical factor is time,” Maj. M. explains. “The treatment window is up to seven days after exposure. A soldier injured in Gaza today can be here tomorrow.”

At the height of the war, up to 50 soldiers a day were treated at the institute.

Over the past two years, thousands of soldiers with hearing damage have been treated there. A recent study found that 88 percent of those who began treatment within seven days showed significant improvement. Sixty percent of soldiers who were initially deemed unfit for combat returned to active service.

Because of the high oxygen concentration, flammable materials, electronic devices, and synthetic clothing are prohibited inside the chamber.

“What do you do for two hours without a phone?” Maj. M. laughs. “You talk, read, play games, solve crosswords.”

‘It felt like a hammer’

Staff Sgt. (res.) M., a combat paramedic from Tel Aviv who served in the Haruv Reconnaissance Unit, nearly missed the critical window for treatment after being injured in Jenin.

“I lost my earplug while running toward a suspect,” he recalls. “A large explosive detonated near us. At first, I heard an endless ringing and thought it would pass.”

It did not.

“I realized I could barely hear from that ear. It was humiliating at 20 years old. I was convinced I was permanently deaf.”

Tests showed severe hearing damage. The speech therapist told him the news was both good and bad. There was an excellent treatment option, but time was running out.

“After a week of treatments, I started noticing improvement,” he says. “I thought it was psychological. Then I saw the graphs climbing back toward normal. After 15 treatments, my hearing was fully restored.”

He returned to his unit in March.

“Thanks to this treatment, my company got another year with a paramedic who was supposed to be out of the army. It’s a win-win. Now I make sure every soldier gets hearing checked after combat.”

For many patients, the chamber becomes more than a medical space.

“You sit there for two hours, disconnected from the world,” M. says. “Young soldiers, veterans from past wars, everyone sharing experiences. It gave me perspective, and it helped me heal, mentally as much as physically.”