A new study by an international team led by researchers from Tel Aviv University presents a surprising way in which simple mechanical structures behave like Lego blocks, enabling them to perform mathematical operations, respond to pressure in stages and even serve as the basis for energy-efficient mechanical computing.

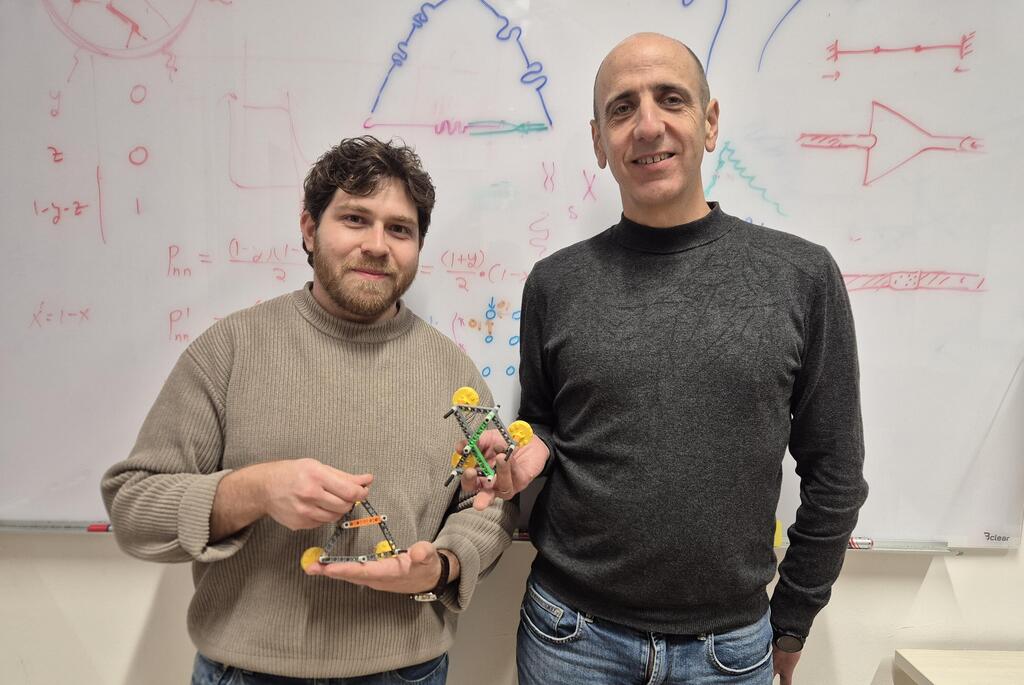

The study, published in the journal Physical Review Letters, was led by Prof. Yair Shokef of Tel Aviv University’s School of Mechanical Engineering, with the participation of undergraduate student Tomer Sigalov and researchers from the Netherlands. It introduces a new method for designing metamaterials — artificial materials whose properties are determined mainly by their shape and structure rather than by the substance from which they are made.

The researchers developed a kind of “Lego kit” made up of triangular building blocks that can be connected in different ways. These connections determine whether a given region of the material is flexible or “frustrated,” a state in which the material would like to deform but the geometry prevents it from doing so. Using simple mathematical rules, it is possible to plan in advance how the material will behave, how many modes of motion it will have and what they will look like.

This “mechanical Lego” approach makes it possible to design materials with complex behavior without relying on heavy simulations or trial and error. As a result, materials can be “assembled” for specific tasks — such as shock absorption, programmed shape changes or mechanical computing — as easily as assembling a model from prefabricated blocks. The concept brings materials science closer to the language of modular engineering and opens a path toward the rapid development of a new generation of smart metamaterials.

The research team explained that one of the study’s most striking achievements is the demonstration of a graded response to pressure: the material does not collapse all at once but folds step by step in a controlled manner. This property is particularly important for applications such as shock absorption, armor and impact protection. Beyond that, the researchers showed that these structures can be used to perform matrix-vector multiplication — a basic mathematical operation in machine learning and artificial intelligence — using only mechanical motion, without electricity or electronics.

“The study shows how smart materials can be built in a way that resembles mechanical Lego,” Prof. Shokef said. “Instead of designing each material from scratch, we used a small number of simple triangular building blocks, each with known behavior. As with Lego, the cleverness is not in the individual block but in how they are connected. A small change in the arrangement creates a big difference in overall behavior — flexibility, stiffness, a graded response to pressure or even the ability to perform calculations. In addition, our work shows that computation does not have to take place only on electronic chips. Logic and computation can be embedded in the material itself.”

This approach aligns with a growing field known as “computing in materia,” which could in the future lead to soft robots, smart sensors and systems that operate for long periods without an external energy source. The development is expected to be applicable to robotics and the construction of technological systems.