Remember the days when we played outside from morning until night, upset only when our parents called us back home? Back when friends were kids from school or the neighborhood, and conversations happened face-to-face or on a landline? Today, most of our communication—with ourselves and with others—happens through smartphones, on social networks, WhatsApp, and more recently, ChatGPT. But how is all of this affecting teenagers?

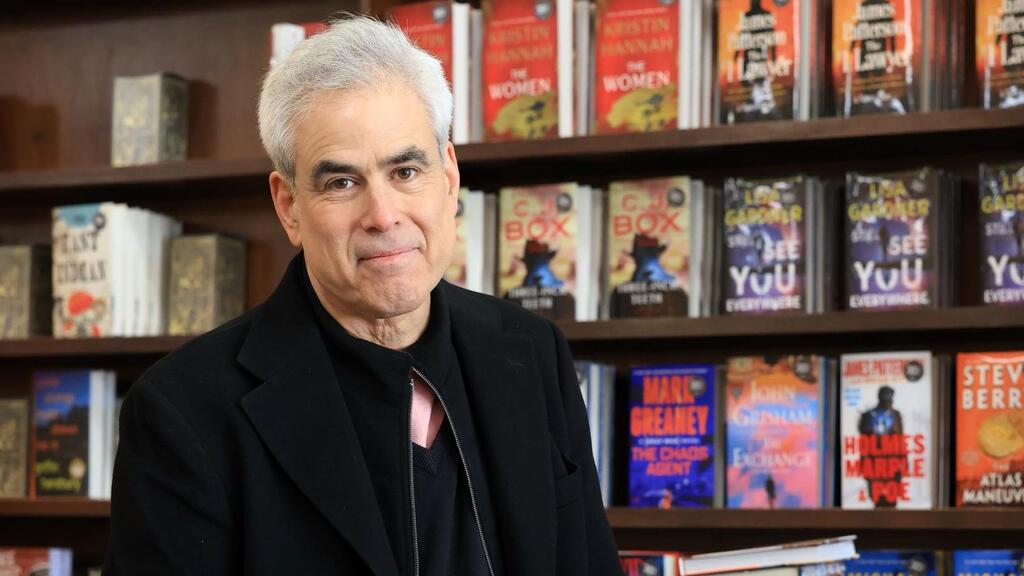

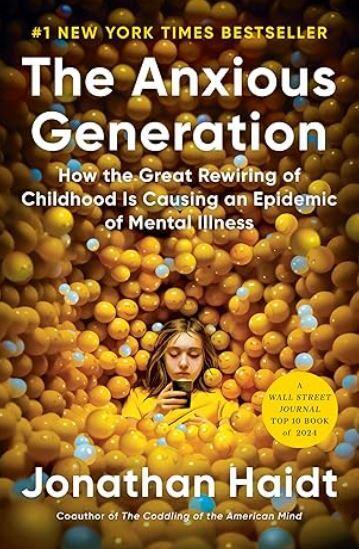

Jonathan Haidt, professor of ethical leadership at NYU Stern School of Business and a scholar of moral and political psychology, has been studying exactly that. His new book, The Anxious Generation, tackles the mental health crisis among teens in the age of smartphones and social media, raising the million-dollar question: How did we lose childhood—and can we get it back?

Like many good things, the book began by accident. “I started writing an academic study about the internet’s impact on democracy,” Haidt explained in an interview. “I wrote a first chapter on mental health and social media’s effect on teens, and it just exploded. I realized this was the issue I needed to pursue.”

According to Haidt, in the early 2010s a quiet but devastating revolution transformed adolescence across the world. The shift coincided with steep declines in teen mental health and a dramatic rise in depression, anxiety, self-harm, and even suicide. He argues this is no coincidence: “Between 2010–2015, the social lives of Generation Z migrated onto smartphones with access to social media, gaming, and more. In my view, this is the single biggest driver of the mental health epidemic that began in the early 2010s.”

Skeptics ask how we know technology—not other crises—is to blame. Haidt responds: “Take Israel, for example. You’ve been at war for two years. Research shows war certainly affects kids, but it often creates solidarity, not necessarily depression or loneliness. By contrast, I’ve studied dozens of countries—across the U.S., Britain, Canada, Australia, the Nordics, Latin America, Europe, and Asia—and everywhere the graphs show the same thing: at that exact time, teens’ mental health declined.”

In The Anxious Generation, Haidt traces the roots of the crisis to two forces: parental overprotection beginning in the 1990s, and the arrival of smartphones and social media. Together, these left kids without the free, unsupervised play experiences crucial to development. Smartphones, he argues, disrupt sleep, reduce social interaction, fragment attention, and foster addictions.

Did the findings surprise you?

“Mostly the scale,” he said. “It’s global. And now we see the impact on students’ attention spans. American students tell me they don’t read books anymore, they can’t sit through a movie. They get bored and flip to TikTok. We’re raising a generation that can’t multitask, that’s less intelligent, and that’s a real problem.”

Haidt also notes sharp gender differences: “Social media harms girls more, especially tweens, with higher rates of anxiety, depression, and self-harm. Girls gravitate to visual platforms like Instagram or TikTok, which drive social comparison. Knowledge is power for them—they want to be included—but it destroys self-esteem. TikTok eats all their attention. Snapchat exposes them to bullying. Boys, on the other hand, get hooked on gaming, porn, and gambling before age 18. They retreat from the real world, don’t build social skills, and lose ambition. No one will want to hire them or marry them.”

What about Generation Alpha, kids born after 2010?

“We don’t know much yet, but it’s reasonable to assume problems will persist, because nothing is improving. In fact, it starts even earlier. By age two, most American kids are already on an iPad or smartphone. In London, 40% of three-year-olds already have phones. Teachers tell me they see four-year-olds with speech delays, and kids who cry in preschool not because they miss their parents, but because their iPads were taken away. Their dopamine drops, and they lose control.”

To counter the shift from “play-based childhood” to “phone-based childhood,” Haidt proposes four simple norms: no smartphones before high school; no social media before age 16; phone-free schools; and much more unsupervised, self-directed play.

Are these realistic? Many parents break down and buy smartphones for social reasons.

“That’s why parents must band together,” Haidt argues. “This only works as a collective norm. Schools must also help. In the U.S., 17 states already have phone-free schools. Brazil banned phones for kids ages 4–9. In those places, kids end up riding bikes again. These reforms aren’t expensive—they just require cooperation.”

Social media harms girls more, especially tweens, with higher rates of anxiety, depression, and self-harm

And what about AI?

“I fear we’ll repeat the same mistakes we made with social media,” he warns. “If kids aren’t stopped, AI will become even more addictive. Children shouldn’t be chatting with AI—those conversations will quickly replace friends and creep into sex talk. Kids don’t need that. Technology makes everything easy, but kids need the hard things—like learning to read, talking face to face, asking real questions.”