An international team of astronomers led by Canadian researchers at the University of British Columbia has discovered something that was not supposed to exist in the universe: a galaxy cluster blazing with hot gas that formed just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang.

The surprising discovery, at the center of a study published in the journal Nature, challenges current models of how galaxy clusters form. According to existing models, such a phenomenon appears only in more mature and stable galaxy clusters later in the life of the universe. The researchers looked back about 12 billion years and focused on a young galaxy cluster known as SPT2349-56.

3 View gallery

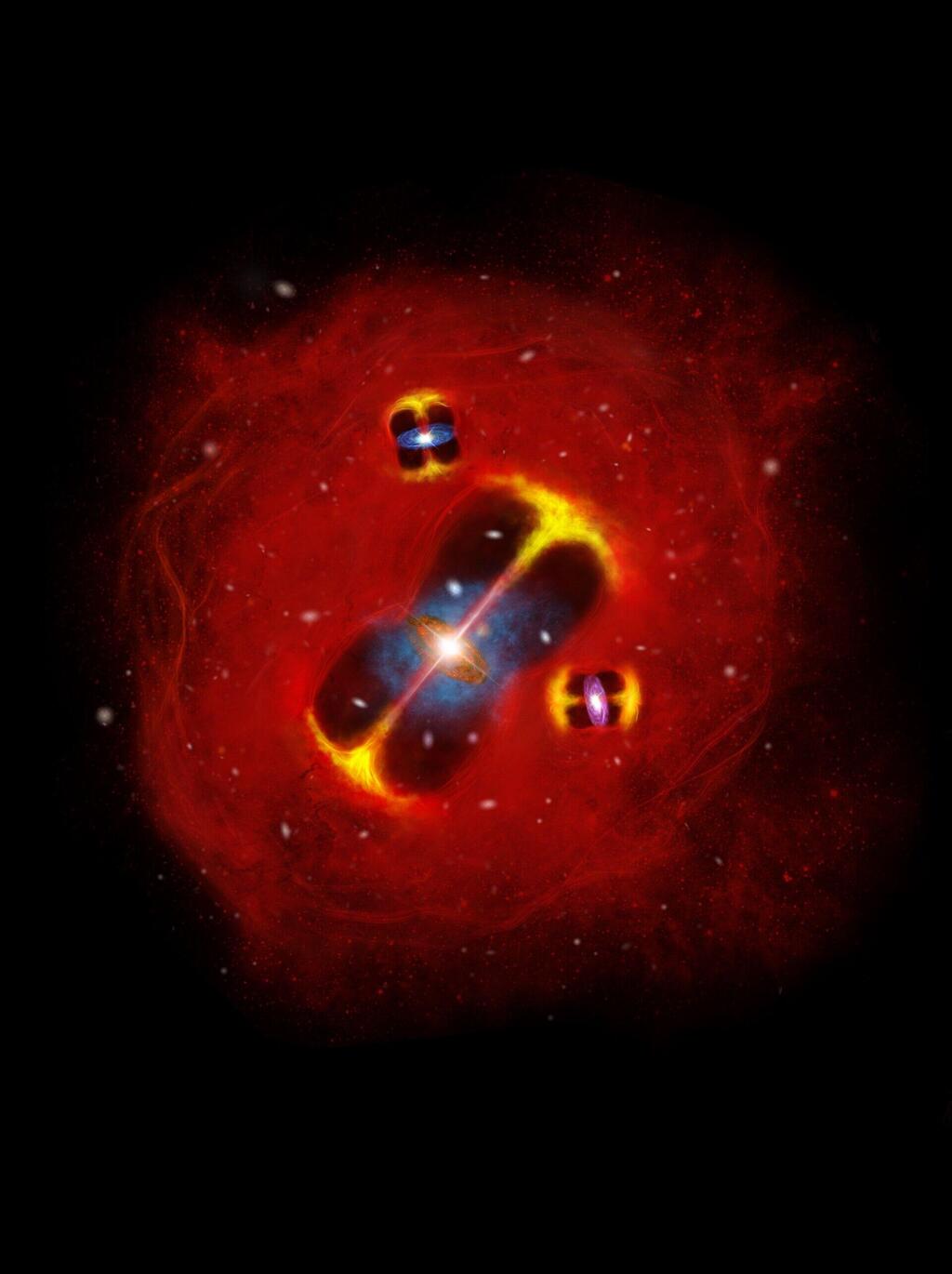

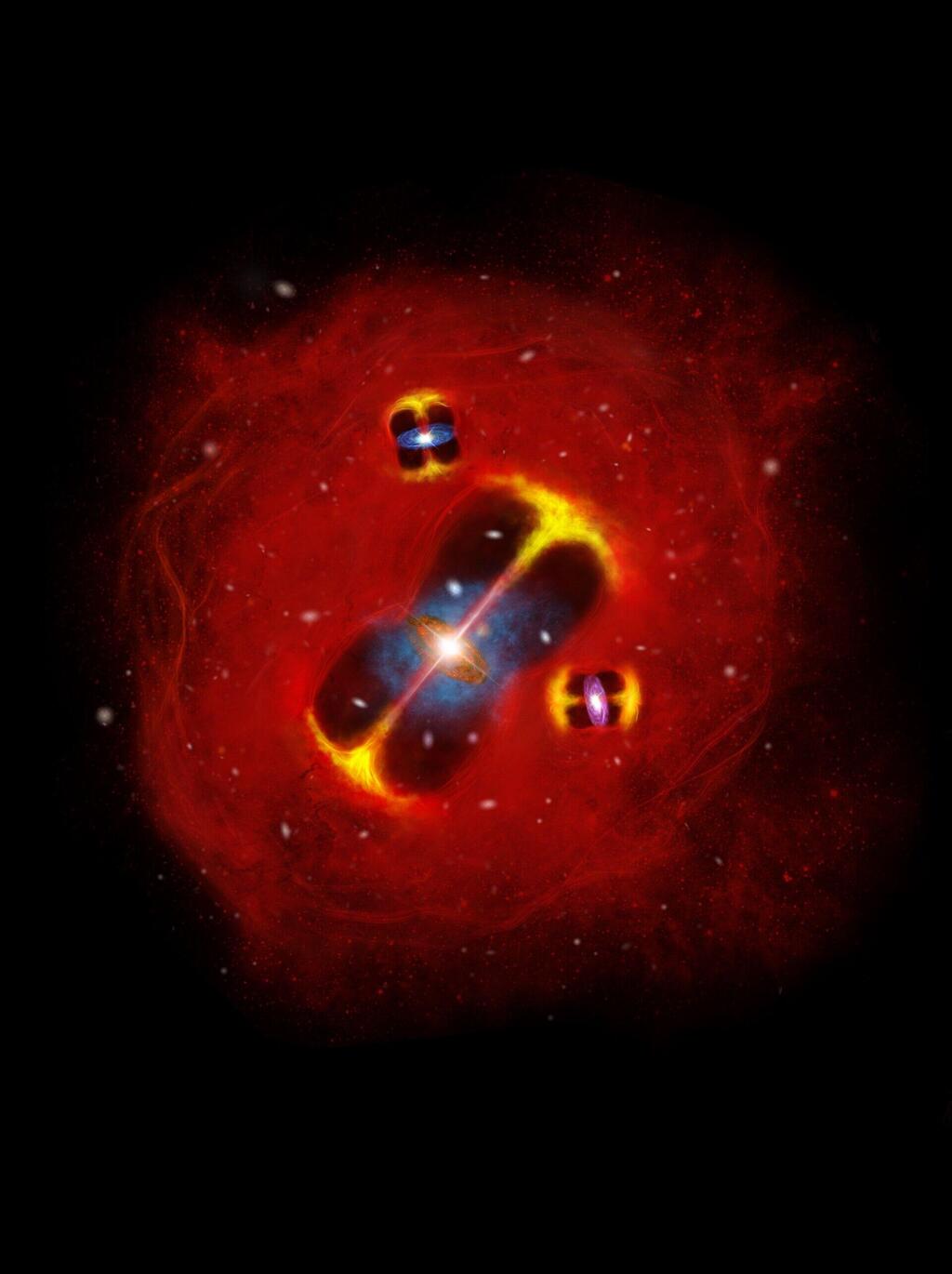

An illustration of the galaxy cluster SPT2349-56 forming in the early universe

(Photo: Lingxiao Yuan)

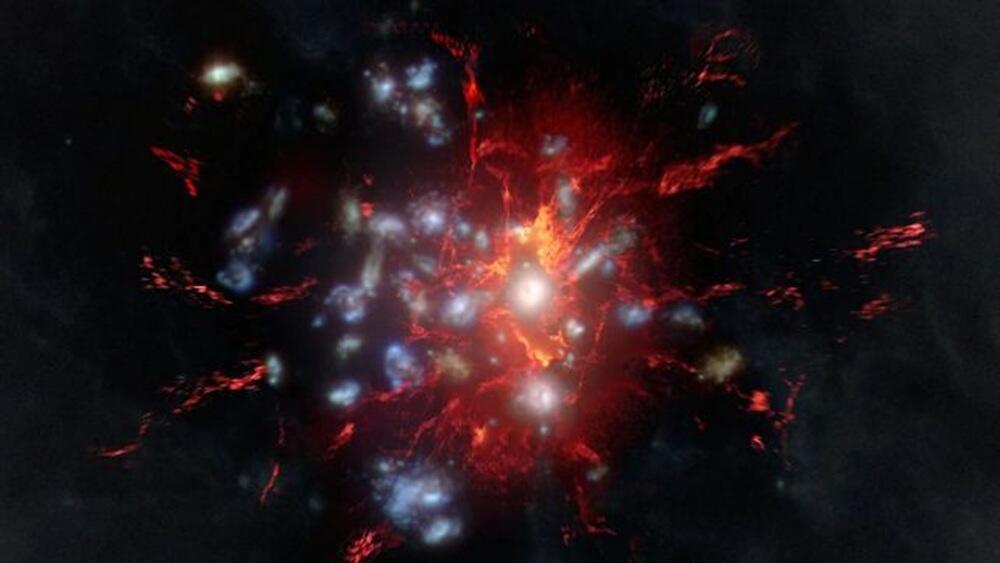

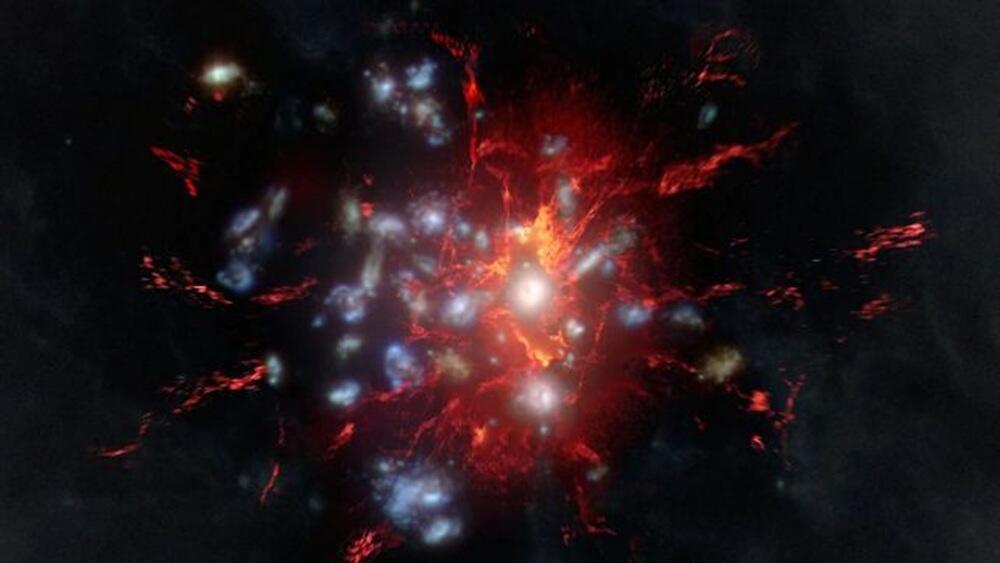

The team used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, better known as ALMA, one of the world’s most advanced astronomical observatories, located at an altitude of about 16,400 feet in Chile’s Atacama Desert. Despite its youth, the cluster is enormous for its age, with a core about 500,000 light-years across, comparable in size to the halo surrounding the Milky Way. It contains more than 30 active galaxies and is forming stars at a rate more than 5,000 times faster than our galaxy, all within a very compact region. Together, these processes funnel vast amounts of energy into the gas spread between the cluster’s galaxies, heating it to an unexpectedly high level so early in the universe’s history.

The study’s authors relied on the Sunyaev-Zeldovich effect, named for Soviet Russian astrophysicist and cosmologist Rashid Sunyaev and Soviet-Jewish physicist Yakov Zeldovich, which allows scientists to calculate the thermal energy of gas between the galaxies in a given cluster. “Understanding galaxy clusters is key to understanding the most massive galaxies in the universe,” said Dr. Chapman. “These massive galaxies mostly reside in clusters, and their evolution is strongly influenced by the extremely powerful cluster environment when they form, including the intracluster medium,” the hot gas found in the space between galaxies within galaxy clusters.

Current models suggest that the vast gas reservoirs that make up the intracluster medium are gradually assembled and then heated through gravitational interactions as a young, unstable galaxy cluster matures and collapses into a stable state. The new finding indicates that this process is more explosive and suggests scientists may need to rethink how galaxy clusters evolve.

3 View gallery

Molecular gas in the intracluster medium of the galaxy cluster SPT2349-56

(Photo: MPIfR/N.Sulzenauer/ALMA)

3 View gallery

the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, known as ALMA

(Photo: Jorge Saenz/AP)

“We did not expect to see such a hot galaxy cluster atmosphere so early in cosmic history,” said the study’s lead author, Dazhi Zhou, a doctoral student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of British Columbia. “In fact, at first I was skeptical of the signal because it was too strong to be real. But after months of verification, we confirmed that this gas is at least five times hotter than expected, and even hotter and more energetic than what we find in many present-day clusters.”

According to Dr. Scott Chapman of the Department of Physics and Atmospheric Science at Dalhousie University, the findings point to the presence of three supermassive black holes in the galaxy cluster, dating back to the early universe. “These three black holes extracted enormous amounts of energy and shaped the young cluster much earlier and more forcefully than we thought,” said Chapman, who was part of the research team while working at Canada’s National Research Council.

The researchers now want to understand how all the pieces fit together. “We want to understand how star formation, active black holes and the overheated atmosphere interact, and what that means for how today’s galaxy clusters were built,” Zhou said. “How can all of this happen at once in such a young and compact system?”