Researchers have uncovered a biological mechanism that allows rats to detect external touch with extraordinary precision, shedding light on a sensory puzzle first identified more than 20 years ago.

In the late 1990s, scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science discovered a unique class of sensory neurons in rat whisker follicles. Unlike most neurons, these remained silent during the rhythmic motion of whisking — the sweeping movement rats use to explore their surroundings — and fired only when a whisker made contact with an object.

3 View gallery

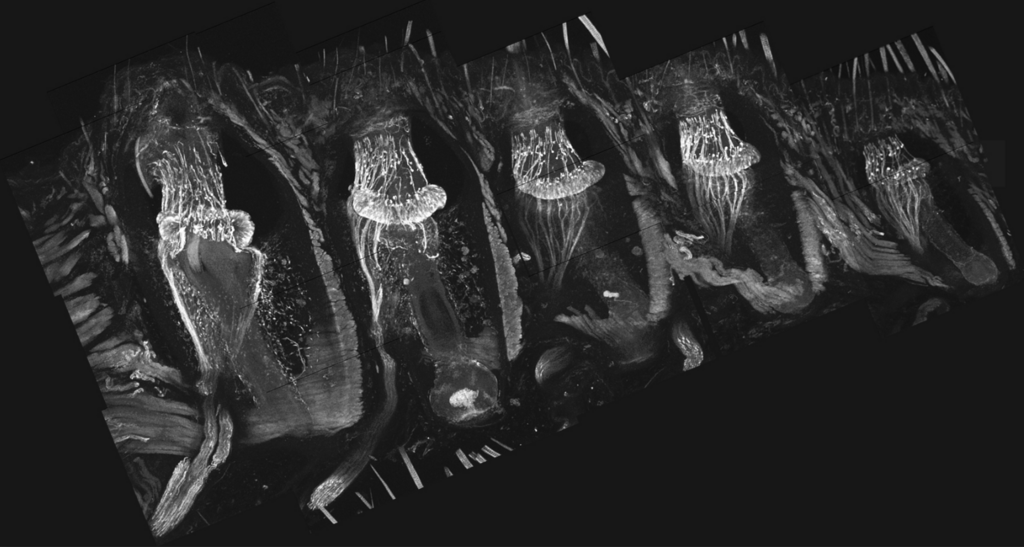

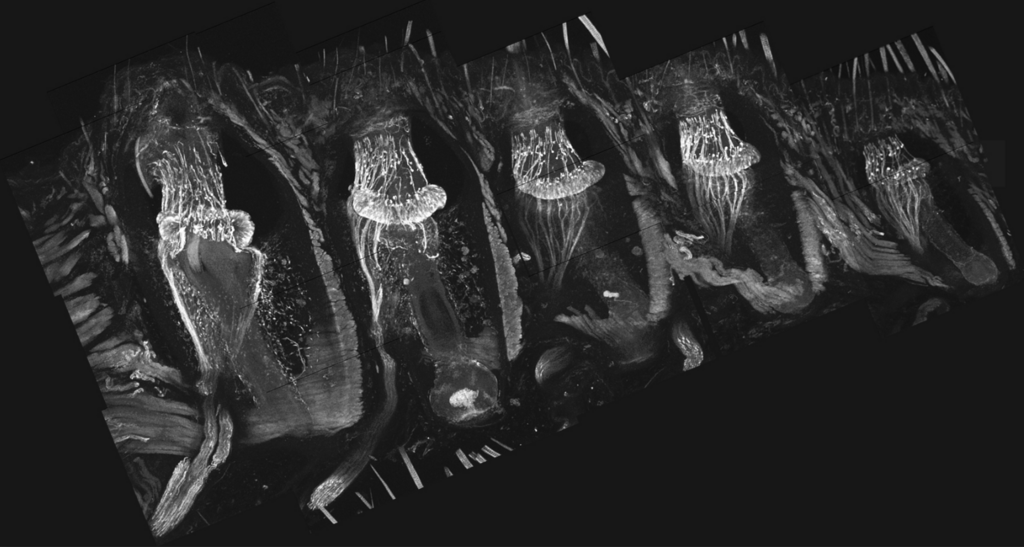

Five whisker follicles in a 100-micron-thick tissue section, viewed under a microscope. Each follicle is enveloped by a thick collagenous capsule surrounded by skeletal muscles. The follicle contains a bundle of mechanoreceptors, whose club-like endings are anchored within a suspended collagen-rich matrix at the level of the upper third of the follicle

(Photo: Courtesy)

That finding raised a key question: how does a sensory system ignore motion generated by the animal itself and respond only to external contact? A new study published Tuesday in Nature Communications offers an evolutionary explanation.

Whiskers in rodents such as rats, mice and hamsters are deeply rooted in specialized follicles packed with mechanoreceptors — clusters of neurons that send tactile information to the brain. Earlier work by Prof. Satomi Ebara of Meiji University in Kyoto showed that mechanoreceptors come in many types, each embedded in distinct follicle layers and tissues. But researchers did not know how these structural differences affected function.

Around the same time, scientists at the Weizmann Institute, including Prof. Ehud Ahissar, Marcin Szwed and Dr. Knarik Bagdasarian, found that mechanoreceptors fall into several functional classes. Some “whisking neurons” responded only to the motion of whisking itself, while others — termed “touch neurons” — activated only when whiskers bent upon touching an external object, remaining dormant during self‑generated motion.

To probe how this selective response is achieved, researchers led by master’s student Taiga Muramoto under Ebara’s supervision revisited the whisker follicle with modern tools. The international team, which included Prof. Takahiro Furuta of Osaka University and Ahissar and Bagdasarian of Weizmann’s Brain Sciences Department, identified a suite of mechanical adaptations within the rat whisker follicle that separate self‑motion from external touch.

They found roughly 50 club‑shaped mechanoreceptors, among the hundreds in each follicle, specialized for active touch. Using scanning electron microscopy, the team showed these receptors are embedded in a collagen‑rich structure that isolates them from vibrations created by whisking. This collagen matrix acts much like a suspended weight in engineering, stabilizing the receptors and preventing them from responding to self‑generated motion.

The receptors are also strategically located: clustered in a single ring near the follicle’s center of mass, close to the pivot point around which the whisker rotates. This mechanically stable zone remains relatively motionless during whisking, allowing the receptors to stay silent until genuine external contact occurs.

Comparative studies suggest these adaptations are specific to animals that rely on active whisking. In cats, for example, club‑like receptors are surrounded by a looser collagen matrix, are not confined to a central ring, and lack the suspended weight structure — features consistent with their lesser reliance on whisker‑based sensing.

“Rats are most active under the cover of darkness and rely on moving their sensitive whiskers to precisely perceive their immediate surroundings,” Ahissar said. “Because they lack well‑developed night vision, whisker‑based sensing is vital to their survival. Evolution has crafted a striking convergence of biomechanics, tissue architecture and sensory-motor processing to solve this fundamental challenge in active touch sensing.”