During his visit to the Gulf this week, President Donald Trump promoted a vision of regional peace and stability tied to economic opportunity. He spoke about artificial intelligence, security, real estate, and investment as potential catalysts of peace. According to a new paper published in The New England Journal of Medicine, there’s another field that might play a crucial role in healing divisions and building bridges between communities in conflict: health care.

1 View gallery

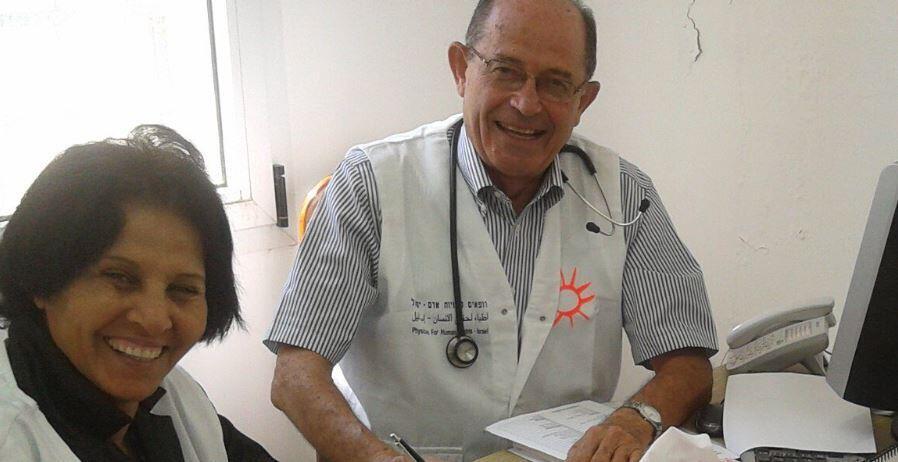

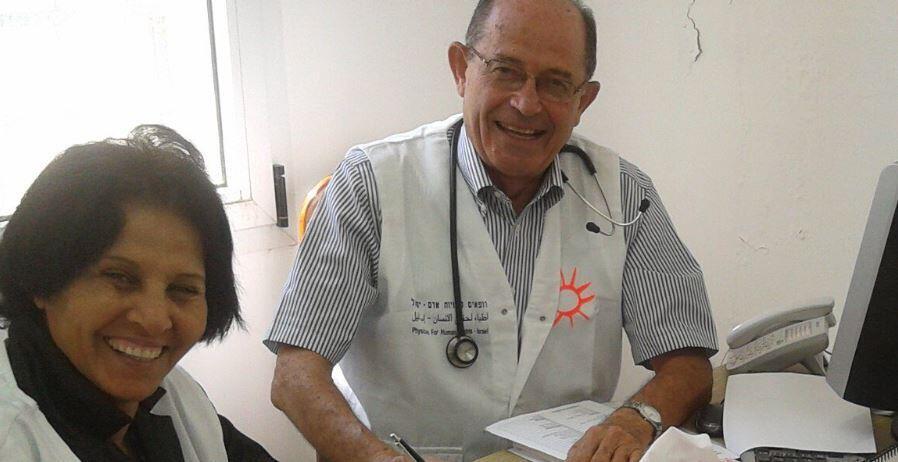

A doctor from Physicians for Human Rights Israel sees a Palestinian patient during a visit of the organization's mobile clinic to the West Bank village of Klil

(Photo: Physicians for Human Rights Israel)

The paper, published by two Jewish Israeli doctors and two Palestinian doctors, found that joint health care programs between Israelis and Palestinians have helped to bring people together who might otherwise view each other with suspicion. “Medicine has the potential to build and strengthen trust between communities in conflict, and it should be leveraged toward that end,” authors Yasmeen Abu Fraiha, Abdalrahman Ahmed, Noam Alon, and Avner Halperin wrote in their paper.

The paper highlighted two joint health programs in particular. One is Road to Recovery, in which Israeli volunteers drive Palestinian patients from checkpoints in Gaza and the West Bank to hospitals inside Israel. While rides from Gaza were halted following the October 7 massacre, the program continues to operate in the West Bank.

Six Road to Recovery volunteers were among those murdered on October 7, 2023. Another volunteer was taken hostage and killed in captivity; his body was returned only recently as part of a ceasefire agreement.

The second program highlighted in the paper, Physicians for Human Rights Israel (PHRI), is a humanitarian aid and advocacy organization led jointly by Israelis and Palestinians. PHRI operates mobile health clinics in Palestinian areas where access to care is limited and advocates for improved medical access and transparency, particularly in light of the collapse of the health care system in Gaza.

The research team identified three key factors contributing to these initiatives’ success in building trust: “equality in participation and decision making, intensity and frequency of interactions, and intentionality in talking about both the conflict and the use of health care programs to build trust.”

They found that open dialogue and acknowledging dual narratives, traumas, and fears are the factors with “the strongest correlation with trust building in joint health care programs.”

“Our findings suggest that cross-national health care programs can overcome formal and informal segregation, establish connections, and help build trust between groups in conflict,” the authors wrote. “Moreover, our interviews and surveys revealed that many Palestinians and Israelis are receptive to working with one another in programs related to health, even in wartime.”

While the two programs highlighted in the journal are Israeli-led efforts to help Palestinians, co-author Avner Halperin told The Media Line that many of the 16 initiatives reviewed are joint ventures. When Israelis and Palestinians share equal roles in running these programs, trust is far more likely to take root, he said.

“Each program is very different and has a different power structure,” he explained. “The more equal they are, the more impactful they are at building trust.”

Halperin said the paper was written during a period of temporary ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, a time when there was hope the war might end with the return of the remaining hostages and a plan to rebuild Gaza. That hope has since faded. But whenever the war does end, Halperin believes rebuilding trust between Israelis and Palestinians must go hand in hand with rebuilding Gaza’s shattered health care system.

“Recognizing that we are facing extremely challenging times, we ask the international health care community to speak out in support of these approaches: immediate rebuilding of health care infrastructure in Gaza, as a joint mission of Palestinians and Israelis; substantial investment in joint health care programs that build trust by facilitating equal, intense, and intentional interactions between Israelis and Palestinians; and establishment of a regional, multilateral professional body dedicated to building trust through health care—all with an ultimate goal of keeping the immeasurable tragedy we have witnessed and experienced from being repeated,” the authors wrote.

Halperin noted that even during wartime, Palestinian doctors continued to treat Jewish patients—and vice versa. That alone, he said, is proof that health care can serve as a bridge between divided communities.

“When major investments are made in building Gaza or other locations with conflicts, this should be taken into account to optimize the positive benefit of health care projects to care for patients and build trust,” he said. “It should be done systematically and mindfully. Then the impact could be much more significant.”

Health care has long been one of the few spheres where Arabs and Jews in Israel work side by side. Arab and Jewish citizens of Israel often entrust their lives to physicians from the other community without hesitation.

Earlier this year, another set of researchers explored this dynamic in hopes of better understanding why the health sector succeeds where others fail. Their study, published in the Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, found signs of real progress in shared society.

“It shows that something positive is happening in terms of shared society,” said co-author Bruce Rosen, who wrote the paper with Sami Miari.

Their study highlights a striking trend: Israeli Arabs are somewhat overrepresented in health care professions, unlike in most other fields across the country, such as law or accounting, where their presence remains minimal.

The paper, written using data from the end of 2023, noted that Arabs comprised just 16% of Israel’s employed workforce, despite making up 21% of the overall population and 22% of working-age adults. But drawing on data from the Central Bureau of Statistics’ Labor Force Survey, the authors found that Arabs comprised 25% of Israel’s physicians, 27% of nurses, 27% of dentists, and a striking 49% of pharmacists under 67.

Arab representation in medicine more than tripled since 2010, from just 8% to 25%. That’s a sharp contrast to fields like law, where Arabs account for only 8% of lawyers, despite making up more than a fifth of the population.

“People go into health professions because they want to help people, and they realize the infinite value of every human being—in this case, Jews, Muslims and Christians,” Rosen told The Media Line. He said that cooperation is built into Israel’s health care system.

Since October 7, 2023, Rosen said he’s heard from colleagues on both sides about a growing hesitation—patients are uncertain whether they would be treated fairly by someone from the other community. Still, he noted, the work has continued.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“There is fear among some Jewish patients and fear among some Arab patients as well that they will not be treated well,” Rosen said. “But I heard it much more in the first few months of the war. It is still out there, but much less than before.”

In their paper, Rosen and Miari concluded that it’s critical to “recognize, appreciate, and maintain” the essential role Arab professionals play in Israel’s health care system.

“Health care professions have been, and continue to be, an important vehicle for social and economic mobility for Israel’s Arab population, offering pathways to white collar employment and social integration,” they wrote.