Scientists at the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology have developed a smart biological adhesive that could change the way wounds are treated and surgeries are performed. The new material, which mimics the natural sticking ability of mollusks on wet surfaces, can bond to tissues within seconds and safely biodegrade inside the body.

For decades, surgeons have relied on stitches and metal staples to close incisions and stop bleeding. While effective, these methods are invasive, painful and can lead to infections. The Technion’s breakthrough offers a less invasive, more tissue-friendly alternative.

The development, patented and recently published in the scientific journal Advanced Materials, is led by Dr. Shady Farah, head of the Laboratory for Advanced Functional Medical Polymers and Smart Drug Delivery Technologies at the Technion’s Faculty of Chemical Engineering.

In an interview with ynet, Farah described how the project was inspired by the natural chemistry of mollusks such as snails, slugs and mussels. “We asked a simple scientific question,” he said. “How do these creatures manage to adhere to smooth, wet surfaces? We wanted to learn from their chemistry and integrate it into our material.”

According to Farah, mollusks use chemical groups known as catechols to create strong bonds that hold even in wet conditions. His team adopted the same chemistry to develop a polymer-based hydrogel capable of mimicking human tissue and adhering rapidly and effectively to different types of tissue.

“One of the main problems with existing biological glues is their inability to bond in wet environments, in addition to poor biocompatibility and imprecise manufacturing,” Farah said. “Most chemical adhesion relies on hydrogen bonds between the material and the tissue, but in the presence of excess water or blood, it’s very difficult to achieve stable adhesion because the water competes for the same bonds. By learning from nature’s chemistry, we managed to overcome this challenge.”

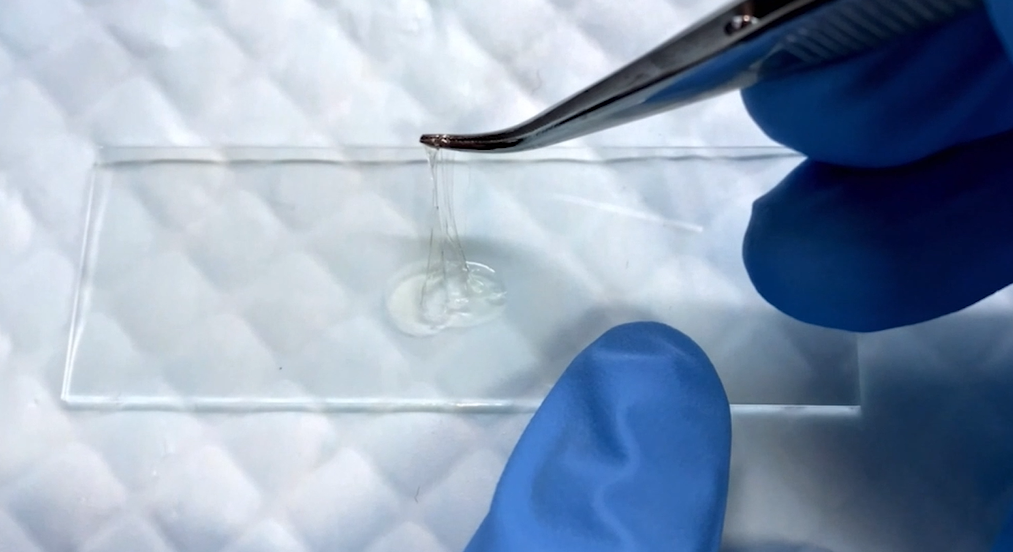

To create the new adhesive, the team used tannic acid, a compound derived from trees and especially common in oak, and chemically modified it with other natural components. The result is a polymer-based hydrogel composed mostly of water, with the remaining material made up of natural, biocompatible substances.

“This structure allows cells to recognize it as tissue-friendly,” Farah said. “When it degrades in the body, it breaks down into harmless natural compounds. That makes it ideal not only as a strong biological glue but also as a biodegradable material whose byproducts are safe for tissue.”

Beyond its composition, the new adhesive is designed for practical use in surgery. “Our goal was to create a smart material that can also be 3D-printed with high resolution and customized to the user,” Farah said. “It also has shape-memory properties. We can fix it in one form, and once it’s inside the body, it transforms into another predesigned shape in response to a physiological trigger. This enables a less invasive, less traumatic surgical process.”

The material was engineered with special chemical groups that allow it to be printed quickly — within seconds — and harden rapidly under ultraviolet light. “It forms into a hydrogel within five to ten seconds of UV exposure,” Farah said. “That allows for high-resolution printing, fast production and precise control over shape. These are smart adhesives — less invasive, less traumatic to the wound area and suitable for stopping bleeding.”

According to Farah, infections remain a major medical concern following surgery. “About 11 out of every 100 people who undergo medical procedures develop infections at the incision site,” he said. “That’s almost 30 million people every year, and at least four million die from bleeding, infections or complications related to those surgeries within 30 days.”

Farah said the Technion team’s adhesive showed strong antibacterial activity against a range of bacteria. “It destroys bacterial cell walls, causing them to die quickly and preventing the formation of pathogenic biofilms,” he said. “This helps prevent potential postoperative complications.”

The new material has already proven effective in multiple laboratory and animal tests. “For example, we used a model called the puncture test,” Farah said. “We took sheep lungs connected to an airflow, made a hole, placed them in water and observed the bubbling. When we applied the adhesive, it immediately sealed the leak. It was a perfect match.”

Additional experiments were performed on rats to stop liver bleeding. “It’s very important to develop materials that meet this huge medical need,” Farah said. “We designed this as a smart surgical sealant that can be inserted through a small opening in a minimally invasive procedure to seal the wound immediately.”

The material has passed all necessary laboratory tests, including full chemical, physical and physicochemical analyses, and successful functional experiments on small animals. “Our next step is to test it in large-animal models that more closely resemble human physiology,” Farah said. “This is the stage before clinical trials. Our plan is to begin large-animal testing within the coming year and then move on to human trials.”

Farah said that beyond its life-saving potential, the development could also improve cosmetic outcomes after surgery. “The goal is to help wounds close with less trauma and less damage to surrounding tissue,” he said. “That means fewer scars and better aesthetic results.”

If successful, the Technion team’s innovation could mark a major leap forward in surgical care — one that could eventually make stitches and staples a relic of the past.