Close encounters of the third kind

An object likely originating from another solar system was spotted on July 1st, hurtling toward the center of our own solar system. This marks only the third object ever identified as very likely to have come from beyond our solar system, following ʻOumuamua in 2017 and Comet 2I/Borisov in 2019. Researchers believe this newly detected object is also a comet and have temporarily named it 3I/ATLAS—denoting the third interstellar (3I) object and the ATLAS telescope array that first detected it.

3I/ATLAS, moving at over 200,000 kilometers per hour (124,000 mph) relative to the Sun, is expected to accelerate as it nears the Sun’s gravitational pull. It was initially discovered by a telescope in Chile, part of NASA’s ATLAS (Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System), which monitors objects that might pose a threat to Earth.

5 View gallery

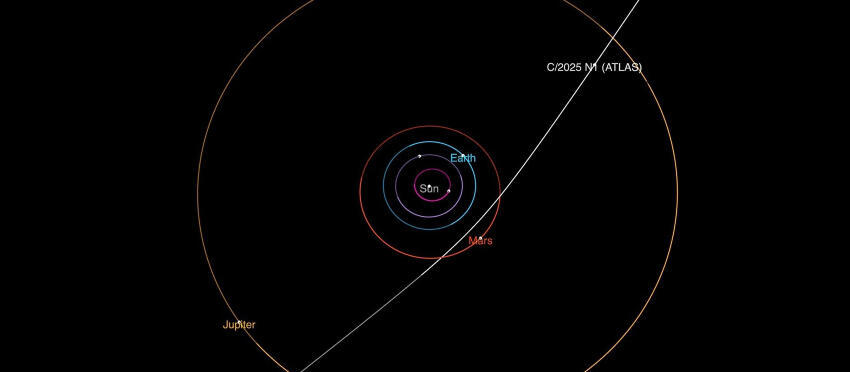

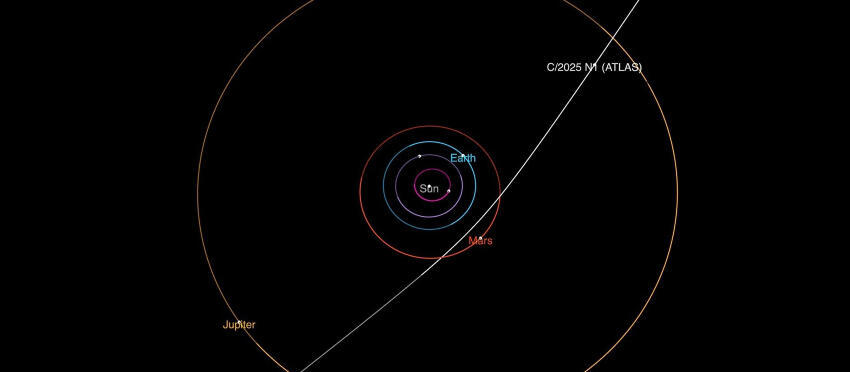

Not expected to collide with Earth. The orbit of 3I/ATLAS, marked as C/2025 N1 in the diagram

(Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

An amateur astronomer later found it in earlier ATLAS images taken in late June. Over 100 observations from telescopes worldwide have since been logged by the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center.

Currently located between Jupiter’s orbit and the asteroid belt, the object will cross Mars’s orbit later in the year, but it is not expected to approach Earth. Its closest point will be about 250 million kilometers (155 million miles) away in December.

“With all the observations, there is no uncertainty that the comet came from interstellar space,” said Paul Chodas, director of the Center for Near Earth Object Studies at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “The speed is too fast to be something that originated within the solar system.”

Researchers believe the comet formed around another star and was likely ejected from its own solar system by a violent event, like a planetary collision, before passing through ours by chance.

“If you trace its orbit backward, it seems to be coming from the center of the galaxy, more or less,” Chodas told The New York Times. “It definitely came from another solar system. We don’t know which one.”

The discovery of ʻOumuamua in 2017 generated enormous interest and speculation in the scientific community—and among UFO and alien life enthusiasts. One of its most vocal supporters was Israeli-American astrophysicist Avi Loeb of Harvard University, who controversially suggested ʻOumuamua could be a product of an alien civilization.

Loeb, commenting on 3I/ATLAS earlier this month, told The New York Times, “This is the most interesting question in my mind right now: what accounts for its very significant brightness?”

If 3I/ATLAS is indeed a comet, its brightness likely comes from sunlight reflecting off jets of gas being released from its surface. Unlike the short-lived appearance of ʻOumuamua, this object will remain visible for months, offering astronomers ample time to study it using both ground- and space-based telescopes.

The environmental satellite that went silent

5 View gallery

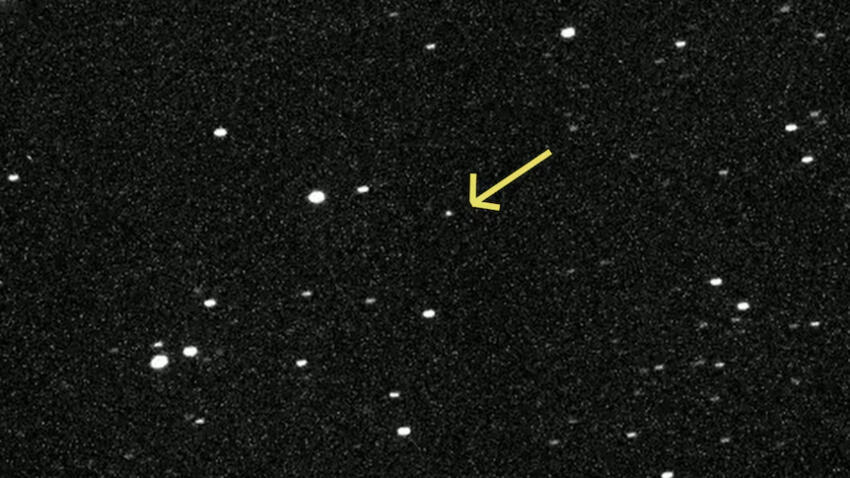

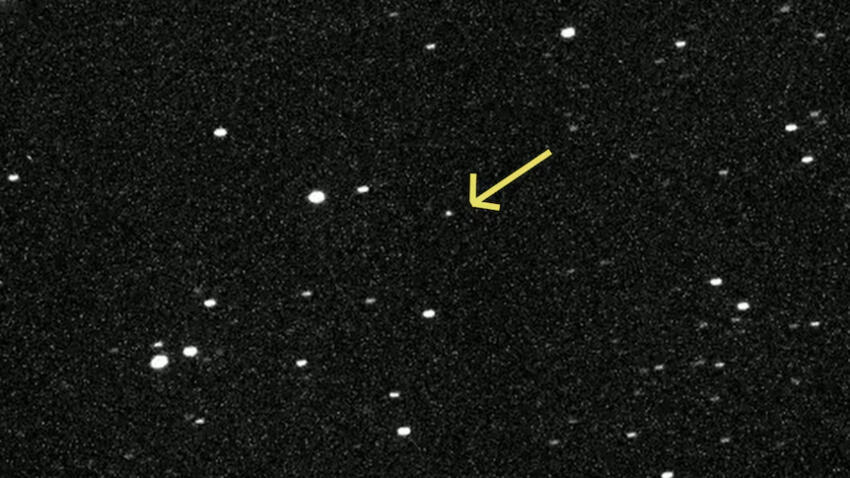

Too early to determine its size, as 3I/ATLAS is still more than 650 million kilometers from the Sun. 3I/ATLAS

(Photo: K Ly / Deep Random Survey / CC-BY-4.0-SA)

An American environmental group recently reported that its methane-monitoring satellite has unexpectedly gone silent just 15 months into what was intended to be a five-year mission. MethaneSAT, launched in March 2024 by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), had been designed to detect and track methane—one of the most potent greenhouse gases—whose levels have recently reached record highs.

Methane is produced by both natural and industrial processes, including animal digestion, wetland decomposition, and oil facility leaks. MethaneSAT was developed to identify even small leaks and pinpoint their exact sources, helping to reduce emissions. Unlike other satellites, it boasted exceptional sensitivity and precision.

Built at a cost of $88 million with funding from Jeff Bezos’s Earth Fund, MethaneSAT ceased communications on June 20. After repeated efforts to reestablish contact failed, EDF declared the mission over. According to the organization, the satellite’s power system failed for reasons still unknown. Engineering teams are working to determine the cause.

“The loss of MethaneSAT, make no mistake, represents a gap in our community’s ability to monitor and quantify methane emissions. And it’s a pretty big gap,” said Riley Duren, CEO of Carbon Mapper, another emissions-monitoring organization.

EDF’s chief scientist Steven Hamburg, who led the project, emphasized that there had been no prior indication of a malfunction or power issue.

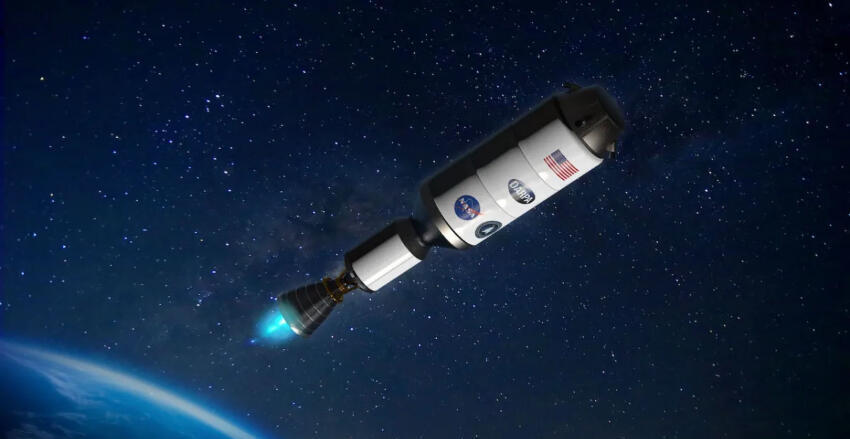

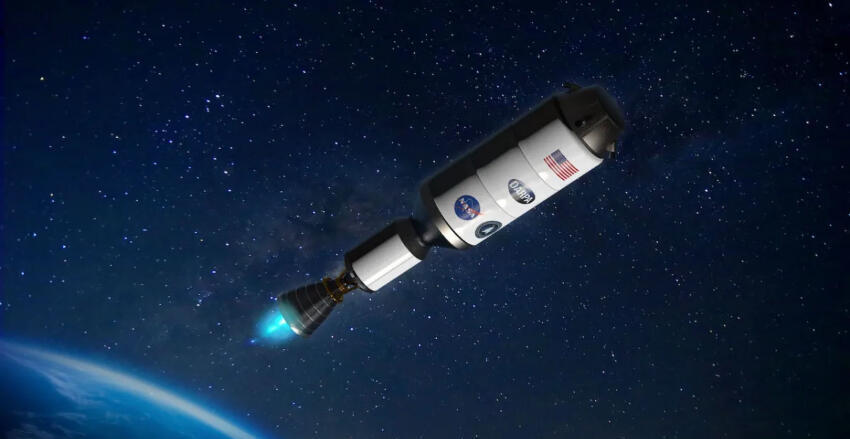

The end of the nuclear spacecraft

The U.S. Defense Department’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is stepping away from developing a nuclear propulsion system for spacecraft, effectively ending the DRACO project it launched with NASA two years ago. Lockheed Martin had been selected to build the spacecraft.

5 View gallery

A significant gap in the ability to monitor methane emissions. Artist’s rendering of the MethaneSAT satellite in space

(Photo: BAE Systems)

Although no formal cancellation has been announced, NASA’s proposed 2026 budget sets funding for the project at zero, following administration-mandated cuts.

DARPA Deputy Director Rob McHenry explained at a recent seminar that decreasing launch costs have undercut the economic rationale for nuclear-thermal propulsion. He also cited a strategic pivot toward nuclear-electric propulsion as a factor.

“As the launch costs came down, the efficiency gain from nuclear-thermal propulsion relative to the massive R&D costs necessary to achieve that technology started to look like less and less of a positive ROI,” McHenry said. “So the national security operational interest in the technology was decreasing proportionally to that perception.”

DRACO would have used a nuclear reactor to superheat hydrogen fuel and expel it for thrust—an efficient process that doesn’t require oxidizers and reduces mass. However, DARPA’s new analysis concluded that nuclear-electric propulsion—where nuclear energy generates electricity to power thrusters—would be a better long-term investment.

McHenry also noted that launching and testing a nuclear reactor proved more technically challenging than anticipated. DRACO now joins a long list of nuclear space projects abandoned for political, economic, military, or safety reasons.

5 View gallery

Now part of the long list of canceled nuclear space projects. Artist's rendering of the DRACO nuclear spacecraft

(Photo: NASA)

“We want to do the disruptive tech,” McHenry said, emphasizing DARPA’s role in fostering innovation rather than refining existing infrastructure.

Routine tourism to the edge of space

Blue Origin completed its 13th suborbital space tourism flight this week, carrying six passengers—five men and one woman—on a brief journey to the edge of space. This brings the company’s total number of space tourists to 70, out of 123 people who’ve flown on suborbital flights so far. The flight also marked the 750th person to ever cross the boundary of space.

5 View gallery

Blue Origin celebrates 70 space tourists. The capsule descends at the end of the mission, landing near the launch pad where the New Shepard rocket also successfully touched down

(Photo: Blue Origin)

The tourists flew aboard the Kármán Line spacecraft, which launched from Blue Origin’s West Texas spaceport atop a New Shepard rocket. The capsule reached an altitude of 105.2 kilometers (65.4 miles), offering several minutes of weightlessness and a spectacular view of Earth before landing safely near the launch site around ten minutes after liftoff. The rocket also completed a successful vertical landing.

Blue Origin has not revealed ticket prices, but seats are estimated to cost several hundred thousand dollars each.