It happened on one of the many intense days of combat in Gaza. Omer Reinhold, a soldier and commander in the Givati Brigade, was sitting with his unit in the brigade commander’s home, deep inside the enclave, when a missile exploded just centimeters above his head.

“We didn’t think too much,” recalls Reinhold, 21, from Ness Ziona, a small town south of Tel Aviv. “We immediately evacuated everyone—because once there’s a hole in the house, you’re exposed to sniper fire. I went downstairs, grabbed two of my soldiers and asked them to check if I was hurt. They tried talking to me, but I realized I couldn’t hear. Just a loud ringing in my ear—unbearably loud. I couldn’t hear anything else.”

That same day, Reinhold was rushed to Sheba Medical Center. “They ran a hearing test and told me I was borderline deaf in my left ear and had 50% hearing loss in the right,” he says. He was treated with steroids and began six weeks of hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

“My hearing came back—but not completely,” he says. “Now I’m extremely sensitive to noise. If people speak loudly, it really overwhelms me. I told my officer I wanted to return to the field, but I started noticing dizziness and constant headaches. At first, I didn’t give it much thought.”

A bloodless wound

It doesn’t bleed, doesn’t show up on scans and leaves no visible mark—but it can change your life. Since the war in Gaza began, growing numbers of soldiers have been reporting injuries caused by blast waves. They return from combat appearing unscathed—only to experience symptoms days or even weeks later: dizziness, ringing in the ears, headaches, chronic fatigue, memory lapses, anxiety, sleep disorders and hypersensitivity to light or sound. Some go months without knowing something is wrong.

Because of his ongoing dizziness and headaches, Reinhold was referred to a neurologist. Meanwhile, his parents started noticing more disturbing signs. “They realized I was forgetting things. I went to the mall, bought some clothes, showed them to my mom and then came home two hours later saying, ‘Come see what I bought.’ She said, ‘You already showed me.’ We started arguing—I got agitated and didn’t understand why.”

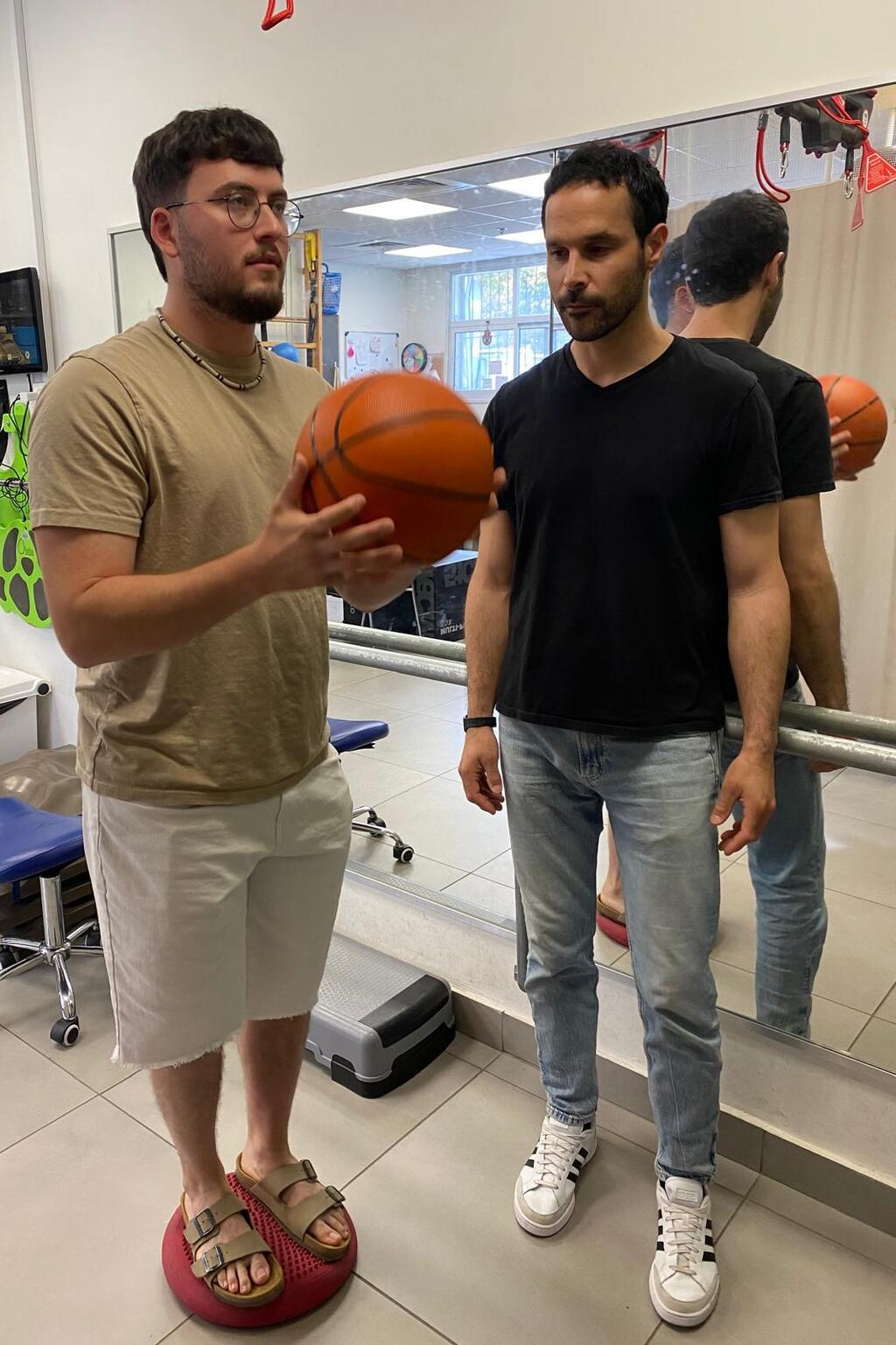

Reinhold during rehabilitation

His emotions were spinning out of control. “I realized I was losing it, and I’m usually a very calm person.”

Eventually, he received a diagnosis. “One neurologist sent me to a memory clinic, but didn’t even examine me. Then I went to another who told me I had post-concussion syndrome,” Reinhold says. “The missile hit just across from me, and the force caused my brain to slam around inside my skull. There was no bleeding—I had an MRI—but the jolt itself was enough to cause a concussion.”

The consequences were widespread: “Memory issues, dizziness, headaches, difficulty sleeping. I’m constantly anxious and exhausted. I’m also extremely sensitive to light—just looking at a lightbulb makes me dizzy. It drives me crazy. It’s a general trauma to the nervous and cognitive systems.”

A diagnosis, but no peace

Even after receiving a name for what he was going through, the struggle continued. “I take sleeping pills, but I don’t sleep. It’s not nightmares or trauma—I just wake up, over and over. The fatigue is constant, and it’s unbearable.”

Before the injury, Reinhold had ADHD. “I’m hyperactive, always on the move, always cheerful. Now I feel like I have no energy. I get bored easily. I used to sit at cafés with friends. Now, ten minutes and I’m ready to leave.”

He adds, “This type of injury is often misdiagnosed—or just brushed off. When someone presents with irritability, insomnia, anxiety, hypersensitivity and restlessness, they’re often labeled with PTSD. But that’s not always the case.”

“It’s similar,” he says, “and I know many people who went through blast exposure, went back to fighting, then got sent to a mental health officer and were told it’s PTSD—because that’s the default assumption. But I know I don’t have PTSD. Others may have been misdiagnosed without even realizing it. I’m sure many are walking around injured and don’t know it.”

A turning point in recovery

Three months after the injury, Reinhold was referred to Reuth Rehabilitation Hospital in Tel Aviv for outpatient therapy. What began as a bureaucratic continuation of treatment turned into a breakthrough.

“I didn’t believe physiotherapy or psychology would help me,” he says. “But then I met Dr. Keren Sivan-Speier. She asked, ‘What bothers you?’ I told her about the memory issues, dizziness and troubles sleeping—basic things anyone could say. I didn’t even mention light sensitivity. Then she asked, ‘Does light bother you?’ and I said, ‘How did you know?’ They understood what I was going through immediately. Their care was personal, warm and empathetic.”

Reuth’s program wasn’t just about coping. It was about rehabilitation—training the nervous system to respond differently. “My physiotherapist Yotam knew how my brain worked,” says Reinhold. “He built a treatment plan that challenged my symptoms and forced my body to learn how to deal with them.”

One exercise involved a special treadmill that shifts unexpectedly—swaying, halting, jolting forward. “While I was walking, they’d throw balls at me or ask me to multitask. It simulated stress and dizziness so I could adapt.”

He also went through biofeedback therapy. “They connect you to a monitor and talk you through everyday triggers—like something that made you angry. You see how your heart rate changes. Then they teach you to bring it down with breathing. It’s powerful.”

Dr. Sivan SpeierPhoto: Gil Dor

Dr. Sivan SpeierPhoto: Gil DorHe received psychological support and occupational therapy as well. “I’ve had ADHD since I was a kid and learned to manage it—multitasking was easy. Now, one tiny noise throws me off. I lose focus immediately. Rehab helped me learn how to navigate that.”

Still attending treatment today, Reinhold wants others to understand that invisible injuries can be just as debilitating as visible ones. “These are wounds the army and medical system don’t always recognize. And soldiers themselves may not realize what’s happening. I’m dealing with it daily—but I’m sure many others are out there, just as lost.”

He pauses. “If my officer hadn’t pushed me to get checked, if I hadn’t seen a neurologist—I’d still be exhausted, in pain and confused, with no clue why. This isn’t just about me. It’s operational. These blast injuries affect everything—how we live, how we fight, how we recover. And we need to start seeing them.”

Invisible trauma, urgent care

Dr. Sivan-Speier, who is the director of Reuth’s outpatient rehabilitation unit and Reinhold’s attending physician, explains that blast-related injuries are among the most common issues affecting soldiers returning from combat.

“This is an indirect injury,” she says. “The body isn’t hit directly, but the force of the blast causes internal movement of the brain—leading to trauma.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

The biggest challenge is that these injuries often go unrecognized. “Soldiers return from the battlefield appearing fine, but they carry a hidden wound. In the chaos of war, visible injuries come first. But that doesn’t mean these invisible ones aren’t there.”

Her team routinely screens soldiers for such trauma—regardless of why they were referred. “We ask about the full scope of their combat experience. Often, there are multiple incidents of minor trauma that went unchecked, and we know these have a cumulative effect.”

Symptoms can include memory loss, difficulty concentrating, confusion, dizziness, ringing in the ears, sensitivity to light and sound, headaches, fatigue, sleep issues and emotional dysregulation. “It’s an injury that hides in plain sight,” she says. “But it directly impacts daily function.”

Recognizing the signs early can make all the difference. “Once they understand what they’re experiencing, they feel less lost. That alone is therapeutic.”

Regaining control

Sivan-Speier remembers meeting Reinhold three months after his injury. “He came in with cognitive issues, light sensitivity, tinnitus, dizziness. He received a full rehab plan, and he’s now finishing treatment with a deeper understanding of his condition—and his family knows how to support him.”

Each soldier receives a customized rehabilitation path, shaped by their needs. “It’s not just physical therapy,” she says. “It’s occupational therapy, psychological counseling and sometimes speech therapy. We use exposure techniques—learning what triggers the symptoms, and gradually building resilience.”

“We treat across every layer—neurological, emotional, functional,” she says. “And we stay in close contact with the soldiers, adjusting their plan as needed. The goal is always to restore stability.”ֿ

The first hurdle is often just recognizing the injury. “Many don’t have the language to describe what they’re feeling. They don’t know what’s wrong. They say, ‘I don’t feel like myself anymore.’ That’s the moment we step in.”

To improve early diagnosis, her team collaborates with military recovery units. “We train medics, officers and hospital staff to be alert. Just because the scans are clear doesn’t mean there’s no injury.”

She concludes with a clear message: “Almost every combat soldier today has experienced blast exposure. Even with helmets and protective gear, repeated trauma adds up. If a soldier comes back feeling ‘off,’ with changes in memory, mood or function, we must consider the possibility of a head injury. You may not see it. But it’s real. And it’s treatable.”