Not long ago, President Trump expressed surprise at the public mood in Israel regarding the issue of fallen hostages. He understood why there is a struggle to bring living captives home, but he was struck by the importance Israelis place on retrieving the bodies of those killed.

It seems the president voiced a widespread sentiment. Many people struggle to understand the strong emotional response that grips our nation around the return of the fallen. Families of hostages often describe the return of their loved ones’ bodies as a homecoming, even though they are no longer alive.

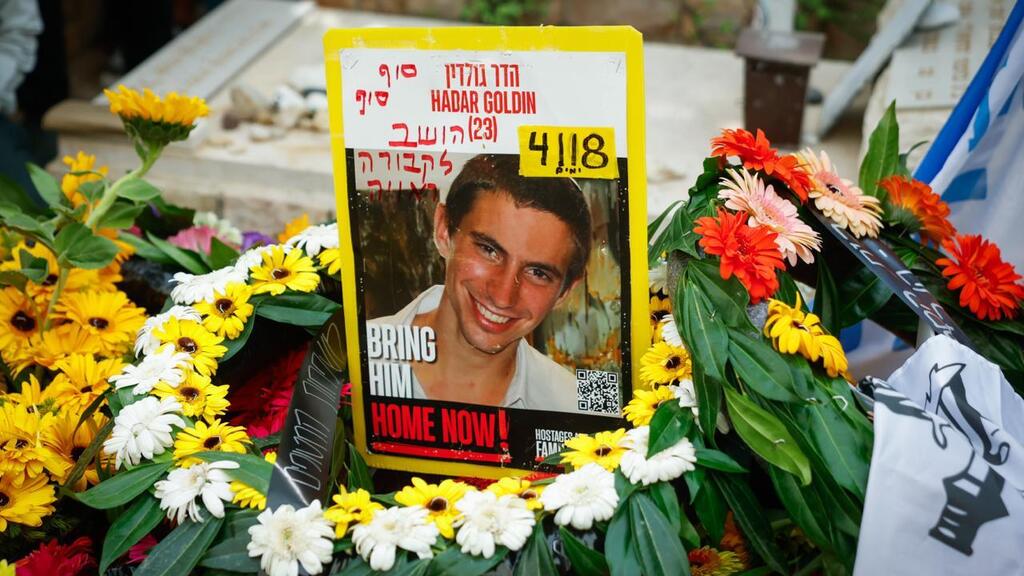

This week, the entire country felt a deep tremor of emotion when Lt. Hadar Goldin, may his memory be a blessing, was finally brought back for burial in Israel after 11 years of heroic efforts by the state and by his family, which showed remarkable courage and resolve. Yet amid this outpouring of emotion, we must ask ourselves why. Why is this so significant? The question becomes sharper for anyone familiar with Jewish tradition and its strong commitment to life and its rejection of excessive focus on death.

This is the same Torah that calls a dead body the highest source of impurity and prohibits anyone who has come in contact with one from entering the Temple or eating sacred offerings. This is the same Torah that bans consulting the dead and fought the pagan religions that sanctified death. Yet in our own tradition we elevate the burial of the dead as a sacred act.

Perhaps the answer lies in this week’s Torah portion, Chayei Sarah. Sarah, the wife of Abraham, dies at the age of 127. Abraham seeks to purchase a burial site for her. The story of his acquisition of the Cave of Machpelah is described in great detail. The Bible devotes no fewer than twenty verses to a full account of the negotiations. Assuming Abraham performed many significant deeds in his lifetime, we must understand why the Torah chose to focus so extensively on this one.

2 View gallery

Hagit and Robi Chen salute at the grave of their son Itay, killed on Oct. 7 and recently returned

(Photo: Paulina Patimer)

Our sages often emphasized that although the land was promised to Abraham, he insisted on purchasing this part of it outright so that no nation could challenge the Jewish claim to it in the future. If that were the story’s main purpose, it did not achieve much. Many recall how Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, later President Chaim Herzog, father of President Isaac Herzog, read these verses aloud before the world. Hostile nations did not alter their attitudes despite the speech and the biblical proof of the purchase.

It is possible that the Torah meant something else entirely. Abraham’s first physical foothold in the land is a burial plot, and this is also the first burial described in the Bible. The portion recounts how Abraham came to mourn Sarah and bury her. Since many people must have died before Sarah, we must ask why the first biblical burial is told about her.

Burial can be viewed as a technical act of respect for the dead. We do not leave a body on the ground like an animal. We provide a dignified place marked with a stone that reflects the person’s deeds and legacy. But choosing a burial place is also a message to future generations. People are typically buried near their families so their loved ones can visit and remember them. When Abraham seeks to bury Sarah in a specific place, in Hebron, he is saying to himself and to those who will follow: this is where I belong. If you want to know who your mother and father were, you will have to return here.

The Goldin family’s heroic struggle to bring Hadar home to the land where he belongs is not only about being able to kneel at his graveside. It is a reminder of what he fought for, what he risked his life for, and why he was killed. He fell so that our people could live in this land and in this state.

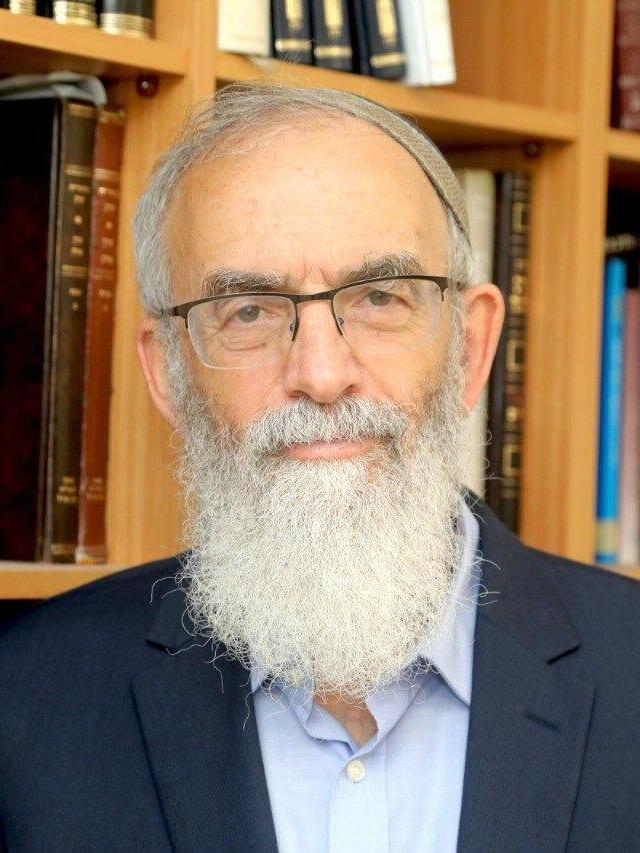

Rabbi David Stav

Rabbi David StavSimilarly, the story of Sarah’s burial is not about solving a shortage of burial space. The Hittites offered Abraham multiple plots, but he refused. He wanted a place for her and for himself, a special inheritance, so their descendants would know they held faith with this place.

The Torah’s account of the purchase of the Cave of Machpelah is not meant to glorify death. It seeks to guide us on how and where to live. An ancient Midrash teaches that a traveler unsure of where the nearest city lies will know he is close when he comes across a cemetery. Just past the cemetery, the Midrash says, one always finds the city.

This is not only a geographical sign. It is a principle. On the way to the city, on the way to life, we pass through the resting places of our dead. Where our loved ones lie, the path to vibrant and rooted life begins.