There is something alluring about the belief in reincarnation. Between the grim prospect of oblivion and the exhausting idea of eternal life in the world to come, the notion that a soul might pass into another body after death, without remembering its previous existence, can seem oddly comforting. But the primary reason this belief made its way into Jewish thought lies in a deeper question that has preoccupied devout Jews for generations: How can the existence of injustice in the world be explained? Or, in more familiar terms: Why do bad things sometimes happen to good people, and good things to bad people?

“This is a central problem in religious thought, often linked to the well-known Talmudic phrase, ‘the righteous suffer while the wicked prosper,’” said Prof. Avishai Bar-Asher, head of the Department of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “Theodicy, the effort to justify God’s actions, is a theological dilemma that has occupied believers of all faiths. How can we explain cases of reward and punishment that don’t seem to match human behavior?”

Reincarnation, he said, offered something of a “magical solution.” If someone could be “blamed” for deeds committed in a past life, the basic model of cause and effect no longer had to apply to a single lifetime. Reincarnation is a core belief in the Druze religion, and that idea serves as the basis for the plot of the television drama “Nutuk.” It is also prevalent in many Eastern religions. In Judaism, by contrast, belief in reincarnation seems to have been accepted and developed only at a relatively late stage—likely not before the Middle Ages.

“In the Bible, where there are hints of different concepts of divine reward, there’s no sign of reincarnation,” said Bar-Asher. “And in the rabbinic literature and the Talmud, we don’t see any real evidence that such a belief was known. That doesn’t mean there weren’t people in the environment of the Babylonian sages who believed in it, but it’s not mentioned.”

He noted that the Talmud often records debates about beliefs and ideas, which helps scholars infer what was known or discussed. “But in the case of reincarnation, it doesn’t seem to have come up. The Talmud does refer to other views on the soul, such as the idea that God gives the soul as a deposit to a person, and upon death, the soul is returned.”

The first concrete Jewish reference to reincarnation appears in the 10th-century philosophical work The Book of Beliefs and Opinions by Rabbi Saadia Gaon, who flatly rejected the idea.

“Some of those who call themselves Jews say that the soul is transferred, which they call transference [reincarnation], meaning that Reuben’s soul can return in Simeon, then in Levi, and then in Judah,” he wrote. “Some even say the human soul can enter an animal, and vice versa. All of this is madness and confusion,” according to a Hebrew translation by Rabbi Judah ibn Tibbon.

“Saadia Gaon was responding to his environment in Iraq, in Babylon, where he was a leading figure,” said Bar-Asher. “He firmly rejected the idea, but from what he wrote, it’s clear that he encountered Jews who believed in this concept in very specific forms. Not only did they exist in his time, but he also felt the need to refute them—so it must have had some footing in rabbinic Judaism of the era.”

“Believers in reincarnation found in it an answer to the question of divine justice, and it’s actually a compelling one,” Bar-Asher said. “If we expand one person’s biography to include others who lived before him, we can then explain how even a blameless infant might suffer great pain or tragedy.”

He noted that Saadia Gaon, who wrote in Judeo-Arabic, did not use the term reincarnation but instead referred to it using a word that can be translated as “transference” or “relocation,” suggesting the soul moves from one place to another and continues to exist. “Reading his writings, it’s clear that Jews who held these beliefs also tried to find biblical justification for them,” Bar-Asher said. “They were actively seeking proof in Scripture.”

What kind of biblical proof did they cite?

“It’s not that these verses explicitly mention reincarnation,” said Bar-Asher, “but for example, in the portion of Nitzavim [Deuteronomy 29], when Moses addresses the people, he says: ‘I am making this covenant… with those who are standing here with us today before the Lord our God, and with those who are not here with us today.’ According to Saadia Gaon, there were Jews who interpreted this as a hint that some souls had already reincarnated, and others had not.”

Bar-Asher added that Saadia Gaon made it clear that these beliefs emerged as an attempt to explain the justice of divine reward and punishment. “The people who believed in reincarnation saw it as a solution to the problem of divine justice—and in some ways, it’s a convincing one. If you expand a person’s biography to include the lives of others who lived before him, then you can explain how a blameless infant might suffer terrible pain or tragedy. Someone else, in a previous incarnation of that soul, sinned—and now, in a new body, the soul is being punished.”

Of course, Saadia Gaon categorically rejected this view. “He offered other, more compelling solutions in his opinion,” Bar-Asher said. “He explicitly favored the approach found in rabbinic tradition—reward in the World to Come. But like many thinkers who came after him, he gave his own interpretation to what that meant. He didn’t accept the idea of reincarnation. Instead, he believed in a simpler view: that each person is given a soul, which must be improved and refined so that it can be returned pure and clean to its Creator. This view was embraced by many Jewish philosophers.”

A long line of rabbis, scholars and Jewish philosophers opposed the idea of reincarnation. Some didn’t address it directly, but rejected the philosophical foundation that would make such a belief possible. Bar-Asher cited Maimonides (Rabbi Moses ben Maimon), saying, “In his fundamental view of the human soul, such a concept is not even possible. According to his philosophy, the soul is the intellect—specifically, a person’s intellectual capacities. Through the development of knowledge and understanding of God, that intellect can reach perfection.”

“For Maimonides, that is how a person attains the World to Come—not by suddenly waking up in a new world, but by having the intellect achieve eternal status once it fully grasps certain truths,” Bar-Asher said.

The turning point of Kabbalah

Among the earliest kabbalists in the 13th century, a noticeable shift took place in attitudes toward the idea of reincarnation. In this context, Bar-Asher points first and foremost to the Bahir, which many scholars regard as the first kabbalistic work.

“The Bahir contains enigmatic parables that look like a sophisticated presentation of the idea of reincarnation,” he said. “It describes a conception in which the human soul, upon death, returns to the tree of souls from which it originated, and then blossoms again from there into another place, potentially appearing in another person. The well-known verse ‘One generation goes and another comes’ is interpreted there as referring to a generation that has already come — that is, one that lived in the past and has returned for another cycle. It seems that the author of this book was a Jew who adopted the idea that a soul can live multiple times, or in multiple contexts, or someone who was educated in such a worldview.”

Nachmanides, Rabbi Moses ben Nachman, also hinted in his Torah commentary at a conception that closely resembles reincarnation, in his discussion of the commandment of levirate marriage, which requires a man to marry his brother’s widow if the brother died childless.

“Nachmanides wrote that levirate marriage conceals one of the great secrets of the Torah, which he linked to the mysteries of creation,” Bar-Asher explained. “As was his custom in such matters, he did not spell out his meaning and spoke in allusions and code. But several interpreters of Nachmanides’ secrets, writing in the following generation, argued that the secret he concealed was that the commandment of levirate marriage is actually based on a principle very similar to reincarnation.”

According to this circle of kabbalists, when a married man dies without children, the ritual of levirate marriage is performed so that his soul, which failed to produce offspring, does not go to waste. “The goal is to preserve and retain the soul of the deceased and ensure that it enters the child who will be born,” Bar-Asher said. “In other words, these kabbalists attributed a hidden logic to the biblical commandment of levirate marriage: It is an attempt to seize a soul left without children, a soul that is essentially suspended. This is not a classical view of reincarnation in which all souls pass through many bodies, but it is reasonable to assume that anyone who articulated such a view believed in some form of reincarnation.”

Another major Jewish mystical source in which reincarnation appears is the Zohar. “The kabbalists who first disseminated the various sections of the Zohar in 13th-century Spain, and who were already familiar with the Kabbalah of the Bahir and with the secrets of Nachmanides, developed these ideas in a very expansive way,” Bar-Asher said. “In several parts of the Zohar, reincarnation appears as a significant concept.”

One example is Saba de-Mishpatim, the Zohar’s homilies on the Torah portion Mishpatim, which attempt to present a theory of reincarnation. According to those texts, the human soul returns after death to its divine source. As described in many places in the Zohar, the soul is hewn from the divine realm of emanation — from what is known as the system of the sefirot — and, if all goes as it should, it returns there after the death of the body. After returning to the treasury of souls within the sefirot, the soul may then re-enter the body of another human being. “The Zohar hints several times that if a person has preserved his soul, has not damaged it or caused it to be lost, it can indeed return,” Bar-Asher said.

According to the scholar of Jewish mysticism, this conception closely resembles the basic idea of reincarnation, with one important difference: The soul does not pass directly from one human body to another, or into an animal. Instead, it first returns to an additional, crucial station in the divine tree of souls. “The idea is that the soul is capable of ascending back to its divine source,” he said, “and only afterward can it return to be reincarnated through conception in the womb of another woman.”

In kabbalistic literature, these ideas are closely tied to the notion of tikkun, or spiritual repair. “Souls descend into human beings in order to undergo processes of refinement — to become more complete, to improve and to grow better. It’s a kind of spiritual ascent,” Bar-Asher explained. “According to these views, people who act negatively and commit wrongdoing not only fail to purify the soul, but actually stain it and damage it. Those defects require the soul to return for another stay in a human body.”

He said the idea creates human drama and connects not only to theories of reward and punishment, but also to the question of humanity’s purpose in the world. “Seen through this lens, if you take it seriously, it profoundly changes how we view the individual,” he said. “You no longer look at a given person as a complete personality, but as a partial entity whose entire mission in life may be to atone for or compensate for the life of a soul that lived once before — perhaps hundreds of years ago, and maybe after several reincarnations.”

“We are used to seeing ourselves as a single subject, living a full life with goals, desires, aspirations and tasks,” Bar-Asher said. “The idea of reincarnation shatters that basic assumption. It tells a person: You might be the reincarnation of someone who lived 200 years ago, while I might be the reincarnation of someone from 700 years ago who has already gone through several cycles. Our story is just a fragment of a much larger biographical narrative.”

Spiritual diagnosis for the soul

Those who took belief in reincarnation to its furthest extreme were the Ari, Rabbi Isaac ben Solomon Luria, and his disciples in 16th-century Safed, foremost among them Rabbi Chaim Vital. “At that point, we are no longer dealing with an occasional paragraph here or a cryptic sentence there, or with compressed ideas that only a select few can decipher,” Bar-Asher said. “This was, famously, an influential circle of scholars that changed the face of Kabbalah forever. One of the areas the Ari focused on and developed, as we know from his students, was the ‘doctrine of reincarnations.’ The Ari attributed to himself the ability to identify which soul resided in each individual.”

In Shaar HaGilgulim (The Gate of Reincarnations), written by Rabbi Chaim Vital and based on the teachings of his master, the Ari, detailed genealogies of reincarnations are laid out. “The students described the Ari’s ability to tell each of them, ‘You are the reincarnation of so-and-so,’ and he also said of himself that he was the reincarnation of this or that figure,” Bar-Asher said. “You see there very intriguing chains of reincarnations.”

Through this attempt to map the cycles of souls, the Ari linked the circle around him to figures from the Bible, to the tannaim, sages of the early rabbinic period, and even to scholars from later generations. “The Ari and his disciples, who of course believed that the Zohar dated to the time of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai in the second century, saw a direct connection between the tannaim who lived then and their own group,” Bar-Asher said.

Prof. J. H. (Yossi) Chajes, who holds the Sir Isaac Wolfson Chair in Jewish Thought in the Department of Jewish History at the University of Haifa, described this as a form of “spiritual diagnosis.”

“The central component of the diagnosis was identifying the previous incarnations of the person who came for treatment,” Chajes said. “That knowledge was necessary for effective treatment, even at the most basic level, to tell a person what his purpose in the world is in the current incarnation, to understand who he is and where he stands in the process of repairing the soul.”

How did the kabbalists explain the fact that the world’s human population keeps growing, along with the number of souls? “They solved that logical problem quite easily — new souls are also created in every generation,” Bar-Asher said. “Figures like the Ari, and others before him, claimed they could tell whether a person standing before them was one of the new souls or not.

“They would look at someone and say, ‘This is definitely not a new soul, it’s an old one,’” he said. “Like a car appraiser who looks at a vehicle from a distance and says, ‘It’s had an engine replacement, even though it looks new.’”

This idea is linked to what is known in Kabbalah as hokhmat ha-partzuf, literally “the wisdom of the face,” or, in modern terms, physiognomy. “They would study a person’s facial features and behavior and diagnose whether this was a new soul entering the world — a tabula rasa — or one that had already been in the shop a few times, meaning it had gone through several reincarnations,” Bar-Asher said.

According to Chajes, there is another question that arises, not entirely different from the first. “If Judaism requires belief in the resurrection of the dead, and one Jewish soul has reincarnated several times over the generations, who exactly will be resurrected?”

One answer given to both questions is that the soul can split. Most kabbalists spoke of the human being as composed of multiple layers, known in Lurianic Kabbalah as nefesh, ruach, neshama, chaya and yechida. Each of these layers can reincarnate independently. In practice, this means that each of us is a kind of composite being, and the configuration present in the current body may be made up of several parts belonging to several different people. “This is how the kabbalists dealt with the complexity of human nature and of each individual person,” Chajes said. “We are not that simple.”

Another related belief is that every soul belongs to a family, determined by the root of that family of souls. According to this view, a person’s true family consists of those who originate from the same spiritual root in the divine realm. “The surprising thing,” Chajes said, “is that according to this conception, you can be born into a family whose members are not actually your true relatives. Life then becomes a kind of mission — to uncover your real family and to create genuine familial closeness.”

Intergenerational repair

Bar-Asher noted that in the foundational medieval conceptions, there were various limitations. For example, on the number of reincarnations. “The idea was usually three times, and that’s it,” he said. “A soul was supposed to reincarnate three times and then complete the process. But we see that this rule did not hold. Later sources already speak of souls that must return again because they still have some additional tasks to fulfill.”

When it comes to personal repair, he said, the idea is usually straightforward: Do this or that, repent, give charity, correct the mistake, compensate someone. “But when we’re talking about intergenerational repair, repair that spans multiple incarnations, it fundamentally changes the entire concept of tikkun. It may be that you are in the world in order to repair the sin of someone who lived hundreds of years ago — someone you never met.”

“You may know nothing about that person, and yet you’re walking around with an unknown mission,” Bar-Asher said. “Your soul is crying out, but you don’t know why.” He compared it to an adopted child who comes to a doctor’s appointment with his parents, but the parents lack the child’s medical history. “A great deal of information is missing. A person is born without sufficient knowledge of the previous data of the soul he carries within him. That’s what creates the need for diagnosis.” A figure like the Ari, he said, would reveal to people who they had been in previous incarnations and would then also write prescriptions for them — detailed guidance on what they needed to do.

How did the kabbalists explain the fact that a person forgets his previous life from an earlier incarnation? In other words, how was the soul’s mechanism of forgetting explained?

“That’s an interesting question, and a range of answers were offered. As noted, in the basic conception that was accepted already in the early stages of Kabbalah, the soul undergoes a crucial process of returning to its divine source in the realm of emanation. Within that built-in mechanism, one can also explain the ‘erasure of consciousness’, or, more precisely in contemporary terms, repression into the unconscious.

“This is where the diagnostician’s aspiration comes in again — to trace those forgotten elements, and sometimes even to awaken them, thereby reducing that forgetting,” he said. “Here, too, you can find a strong Platonic idea of ‘recollection,’ similar to the well-known rabbinic teaching about the infant who forgets all the Torah he learned in his mother’s womb, and then, over the course of his life, essentially reconstructs that memory.”

So the ultimate goal was to reach a state of repair, so that the soul would not have to reincarnate again?

“Yes, that’s a fair way to put it. You could say it began as yet another attempt by human beings to answer the eternal question of why injustice exists. But as the idea developed, it ultimately reshaped the entire way life was understood. “In this worldview, a person sees himself as someone who is continuing another story — a story that will probably continue long after his own lifetime ends. That gives life a completely different direction.”

That’s interesting, because when I think about the appeal of reincarnation, it feels like a kind of middle solution between oblivion and eternal life, concepts the human mind can’t really grasp.

“That’s true. But humanity’s fascination with eternal life has never faded. Even today, there are futurists who promise that by the end of this century, medical breakthroughs will make it possible to dramatically extend human life spans. Maybe such a breakthrough will happen, and maybe it won’t — I have no idea.

“But it seems to me that in all of those fantasies, a person wants to remain himself. He doesn’t want to become someone else. And that’s a crucial difference from the shift in consciousness that comes with the idea of reincarnation.”

Bar-Asher warned that belief in reincarnation can also have darker implications. “It can open the door to abuse and to the awakening of very dark impulses,” he said. “From both an ethical and a legal standpoint, it fundamentally undermines the definition of the subject. And that destabilization can have severe and destructive consequences for freedom, human dignity and individual rights.”

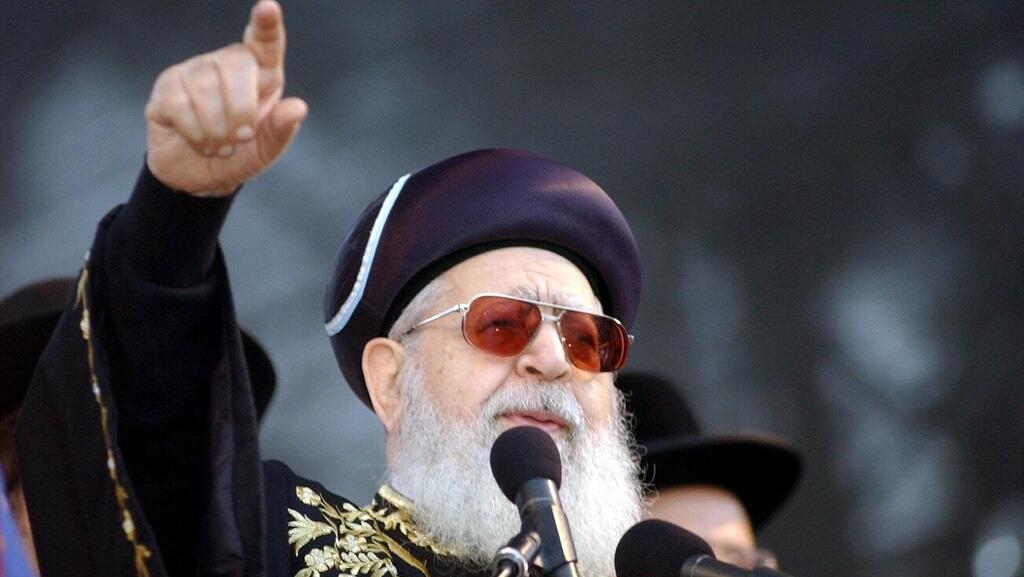

Under the influence of Lurianic Kabbalah, belief in reincarnation made its way into the Hasidic world. At times, it also spilled over into other circles. In 2000, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef sparked a public outcry when he claimed that millions of those murdered in the Holocaust were reincarnations of people who had sinned in a previous life. The remark was received with shock by the general public, but even in this case, the idea of reincarnation was being used in an attempt to resolve a theological problem: How can catastrophes that befall good and upright people be explained?

Today, belief in reincarnation is considered legitimate within the religious Jewish world. “If more than a thousand years ago Rabbi Saadia Gaon went to war against this idea, today there is no problem at all speaking or writing about reincarnation,” Bar-Asher said. “In the eyes of many, it is perceived as an ancient and authentic Jewish belief — even though it clearly originates in external sources, and even though it still has many opponents within Judaism.”

Even so, belief in reincarnation is far less central in Judaism than it is, for example, in the Druze world. “If you went into Daliyat al-Karmel and spoke with Druze residents, someone might tell you, ‘Yes, my son is the reincarnation of so-and-so, and I am the reincarnation of someone else,’” said Prof. Chajes. “In other words, reincarnation functions there on a day-to-day level. It is part of the fabric of Druze communal life.

“Among Hasidic Jews, it exists more on the level of thought,” he said. “Kabbalistic books sit on the shelves of the rebbes and nourish their thinking, but I’m not sure it is all that central in the lived world of Hasidim. I don’t get the impression that reincarnation is especially present in everyday Hasidic discourse.”