In May 2014, Tsuriel Sdomi, director of the Israeli Plectrum Orchestra, was invited to lecture at the University of Bad Bühl in Stuttgart. After the concert, a cocktail party was held in a nearby palace.

Sdomi did not imagine that a random conversation he struck up there would change his life - and turn into a new novel that raises serious questions about morality, identity and atonement.

"It was a flashy event with many important people", Sdomi recalls. "Very quickly, a tall, impressive man, about ninety years old, with a mane of bleached blond hair and blue eyes, approached me. He held a glass of red wine and offered me one. He asked me in English if I was from the Israeli orchestra, and I told him yes. He complimented my playing and said, 'Your orchestra plays like German musicians. Precise and brilliant playing, but with a lot of chutzpa.'

"I innocently asked him, 'Okay. You love Israel, but still, why do you come to Israel so often?' And he said to me with a smile, 'I probably have hundreds of children in Israel.' He told me about the day he came across a small ad hanging on the university bulletin board seeking potential sperm donors for pay. According to him, this was an opportunity for him to atone for the atrocities his father committed against Jews during the Holocaust."

"He asked why we chose to play Bach, and I explained to him that 'Bach is their God.' He started speaking in Hebrew, and my jaw dropped. I was surprised and asked him, 'Where did this Hebrew come from?' He explained at length that in the late 1950s, he first visited Israel as a medical student on a student exchange with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and fell in love.

"He talked about his trips around the country, about the weather in Israel and how wonderful it is here in the winter. He joked that on Zamenhof Street in Tel Aviv, he felt more German than in Germany because there are so many Yekkes (Jews of German-speaking origin) there.

"I innocently asked him, 'Okay. You love Israel, but still, why do you come to Israel so often?' And he said to me with a smile, 'I probably have hundreds of children in Israel.' I asked him what that meant. In response, he told me about the day he came across a small ad hanging on the university bulletin board seeking potential sperm donors for pay. According to him, this was an opportunity for him to atone for the atrocities his father committed against Jews during the Holocaust. He explicitly said, 'This was my way of atoning for my father's sins,' and emphasized that he didn't take the money out of an act of atonement.

"He spoke cynically, but he didn't try to gloss over it," Sdomi recalled. "I felt like he had been waiting years to share the story. I had conversations in the past with Germans who cried when they told me about their father, who was a Nazi. Here it was different: full of himself, polite, smiling. I remember asking him in surprise, 'Did they accept you? Did they let you donate?' and he replied with a smile, 'Don't look at me like that.' In my book, he is the character of the doctor who meets Wilhelm at a doctors' conference in England. The same self-confidence. The same cynicism."

Sdomi shares that his then-partner, an Israeli living in Germany, was also present at this conversation, and she was shocked by his story. "I said, 'Wow. Well done.' I was enthusiastic about the altruistic contribution. She was suspicious. She also didn't like listening to what he said. At first, she told me, 'He's cynical. I don't like his smile."

How did he respond to her?

"With blatant disregard. When she spoke, it was in German and he would give her a laconic and short answer, while with me, he spoke at length and smiled. It's interesting, maybe he wanted to see how I, as a Jew, as an Israeli, would react to the things he said.

"When we left, my partner was quieter than usual. Only in the hotel room did she ask me if I really didn't understand what he said had meant. I replied, 'Well, he did the State of Israel a favor,' and asked her not to make a scene about it. I will never forget the look she had when she told me, 'That's the deal. Don't you get it?' And then she started talking a lot and chain-smoking.

"Only then did the penny drop suddenly and powerfully. It confused me. It's so monstrous that I can understand the shock, and on the other hand, how it brought to mind interviews with Birgitta Hess, the daughter of Rudolf Hess, the commander of Auschwitz, and how she sounded like a good woman who wanted to deal with her father's monstrous legacy. I remember well a sentence she said, 'I don't want to have children because I'm afraid that evil will be passed on through inheritance.' That sentence shocked me. It made me understand the complexity of the matter. Not black and white."

Did you feel that this was a real "atonement" on his part or a story that obscures responsibility?

"I don't think he wanted atonement, nor were there any attempts to obscure anything. Here it was something else."

Between reality and fiction

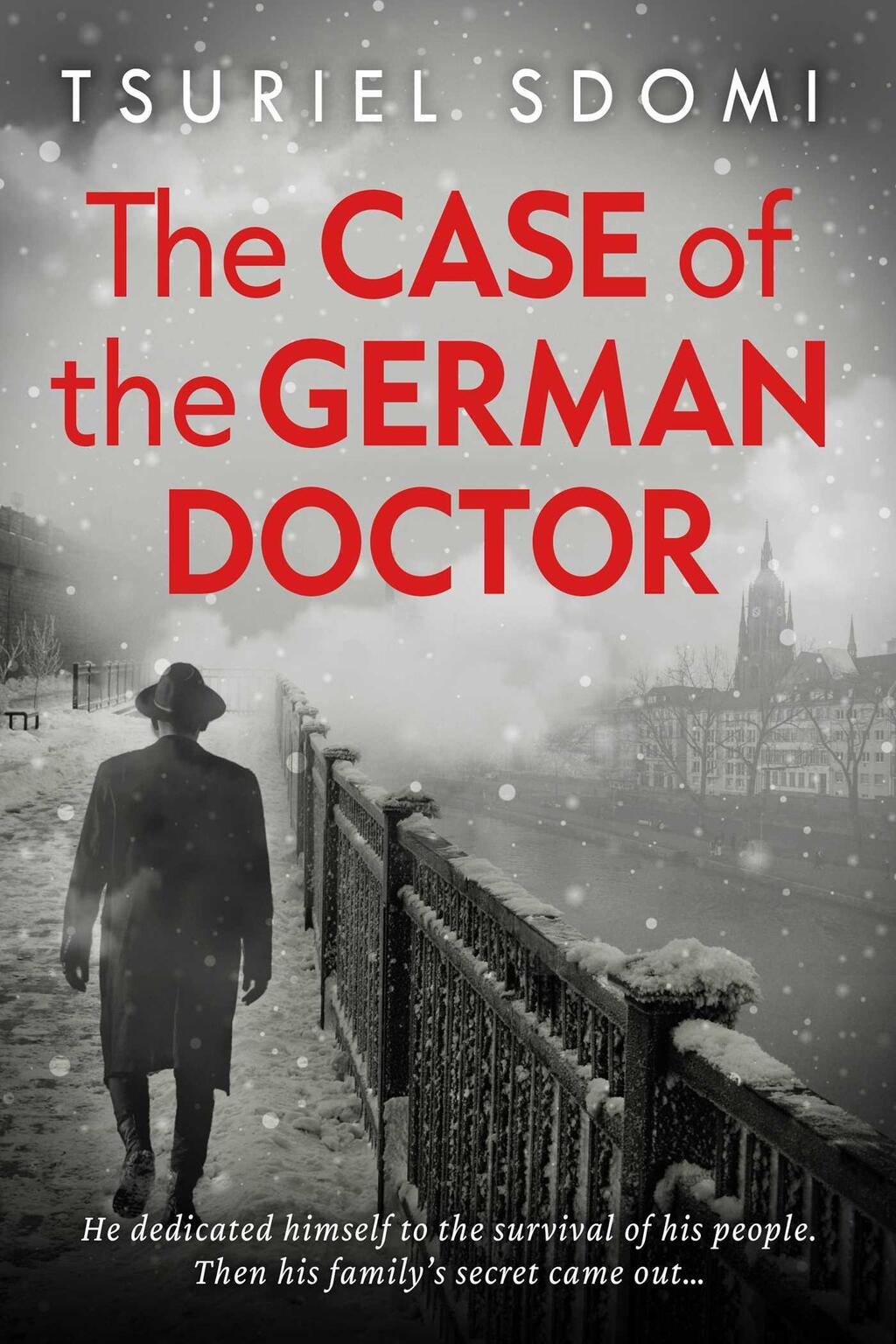

"This encounter became the starting point for Sdomi's book The Case of the German Doctor. The plot touches the most vulnerable nerves: an American doctor of German origin, with the help of his cousin – a geneticist with a Nazi past, dedicates his life and fortune to impregnating Jewish women who are Holocaust survivors. He is later charged in a show trial for 'attempted genocide' because he impregnated them with his sperm without their knowledge.

Throughout the book, which moves between reality and fiction, one painful question arose in my mind: Can past sins really be atoned for – or can they only be immortalized in “new blood"?

"The truth is, this is not the first time I have been asked about this, and it is an amazing question to me. Is it really possible to atone for atrocities like the Holocaust? And more than that, does anyone, except the dead themselves, have the right to accept such atonement and forgiveness? We all experienced turmoil on October 7 with the atrocities of the Nova music festival, and this does not even come close to the mass, planned and systematic genocide that took place in the Holocaust. These questions also concern the role of Germany today and the education of the future generation. I was once asked what I thought of immigrants in Germany, and I replied that, in my opinion, they are a kind of correction for what was done to the Jews in the Holocaust. Think about it."

On the penultimate page of The Case of the German Doctor, it is noted that the three children of Ida Goldstone, who was fertilized with Dr. Wilhelm's sperm, "were born healthy, intelligent, well-educated. All of them have warm Jewish hearts. Not a drop of evil was mixed in their blood." What did you actually want to convey with that?

"That even though Ida, Goldstone's wife, was impregnated by the doctor and the evil was supposed to be passed on to them by inheritance, the children turned out great. In other words, it means that nothing is absolute and ultimately education has a decisive significance in shaping the character of the children."

Regarding the message he wanted to leave with his readers, he says in a critical tone: "At the heart it lies the question: Is evil inherited? It affects many things and raises questions of what's moral or not. And as the world progresses, the complexities become greater. Heredity and genetics and the attempt at genetic cloning, as the Germans sought to create, led to monstrous things, and this does not only belong to World War II. We are in the midst of this today as well. It is a fact that, according to studies, the highest demand among women seeking sperm donations is for children with fair hair and fair eyes. So this does not only belong to the Holocaust — it is a moral complexity that is still alive today."

What were the initial reactions to the book's draft?

"Professionals in Israel and around the world were very enthusiastic about it. An Italian writer wrote to me that he was mesmerized by the writing. A British writer wrote about me really wonderfully. Okay. There will be some scoundrels who will criticize, and I will accept that with love because when I write, I don't come to please anyone, certainly not with a story like this."

He shares that one of the editors of a publishing house in Israel asked him to "lighten things up. It's heavy." And he refused. "Look, Tuvia Tenenbaum, an Israeli-American writer, wrote the best-seller I Sleep in Hitler's Room at the request of the German publishing house Robolt. He traveled around Germany for a year at their expense and wrote about the new Germany. The result was a shocking document about the antisemitism that exists there. Although it is disguised with a great deal of subtlety, it exists. The publishing house pressured and demanded that he change everything and remove the antisemitic references, and he simply refused. So I am not alone in this fight."

According to him, others have also asked him to soften the story, but he refused. "It’s clear to me this is a provocative book and parts of it aren’t easy to read. To be honest, I do have concerns about how readers will receive it, but not in a way that would make me back down. Still, the book is important and raises a lot of questions and thoughts among Israelis and Jews in general, and I trust that readers will deal with the uncensored version. The next novel will be lighter. I promise," he says with a smile.

Sdomi, who has lived in Rosh HaAyin for most of his years, brings up with a smile his personal point as a member of the Yemenite community, "I'm always sent to write about Yemenite children, as if someone has a monopoly on material like the Holocaust. However, I definitely plan to write a book about the Yemenite children's abduction. I have a lot of archival material and also stories from my family."

He touches on the increasing use of the word "Nazi" in Israeli public discourse and warns: "In Europe, they use exactly the same terminology of the Holocaust that we use here in Israel, and that's the great injustice."

“They were considered a ‘select breed’ — talented, from good and well-off families who could afford many years of study, along with all sorts of similar stereotypes. Of course, it was done for payment, and the treatments were carried out secretly; everything was done informally, rudimentary and improvised."

About the events of October 7, he says: "October 7 was a horrific event, but to compare it to the Holocaust? And this book comes to diagnose the absolute, pure evil of a completely sane people who deliberately and silently planned the murder of a nation."

Sdomi smiles, and for a moment, he looks like a little boy sharing a secret: "And I have another obsession with the Germans: to understand the madness of this elegant, rational, orderly people that suddenly turned. That's why it's important to me that the book be published in Germany and in the German language."

Sounds like the beginning of a historical indictment.

"It sounds like the beginning of a movie, and by the way, I've already cast Helen Mirren, Judi Dench, Antonio Hopkins and Dustin Hoffman in the lead roles. Hoffman will play Goldstone, a proud Jew."

Forget the trauma. Let's talk about Italy.

I first met Sdomi, an impressive and tormented figure, in the mourning tent at his home in Rosh HaAyin. He was wrapped in a white prayer shawl, surrounded by those offering condolences — a bereaved father, a modest man who looked far younger than his 60 years. Over time, I came to know him as an eternal child who never stops creating and reinventing himself, far beyond the official titles listed on his book jacket: lawyer, writer and multidisciplinary artist. He holds degrees in biochemistry and law from Bar-Ilan University, studied painting and sculpture in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, trained in Baltimore in the United States, and at the International School in Umbria, Italy.

When I carefully ask how the loss he experienced affects his writing and his dealings with trauma, such as the Holocaust, his answer is firm: "This point is heavy for me. Let's talk about Italy, about the fact that I love people, love traveling, fascinated by discovering new places. My encounters with the German people, as well as the Italian people, also grew out of this inquisitive and curious place. This is where it all begins."

The silent history of sperm donation

The story that Sdomi tells corresponds with the research of Prof. Daphna Birenbaum-Carmeli, a sociologist and anthropologist at the University of Haifa, who, with her late husband, Prof. Yoram Carmeli, wrote the book Kin, Gene, Community: Reproductive Technologies among Jewish Israelis, which deals with fertility technologies in Israel.

4 View gallery

Prof. Daphna Birenbaum-Carmeli and her late husband Prof. Yoram Carmeli

(Photo: Courtesy)

Precisely because sperm donation is a very simple and basic technology, "it remained under the radar for many years," explains Prof. Birenbaum-Carmeli, "when the attending physician had a lot of discretion. In fact, until the 1980s, there was no regulated policy on the subject, and only with the discovery of the AIDS virus did the field come under regulation."

What were the years before regulation like? According to the professor, it was an unofficial "shadow industry" in which many of the donors were medical students selected by doctors who knew them during their studies or internships.

“They were considered a ‘select breed’ — talented, from good and well-off families who could afford many years of study, along with all sorts of similar stereotypes. Of course, it was done for payment, and the treatments were carried out secretly; everything was done informally, rudimentary and improvised. The doctor would ask the donor about family illnesses and sperm quality, but usually no tests were done to verify his answers. Only in the 1980s did regulations begin to tighten and the treatment enter into a regulated system. Donor sperm had to be frozen, and the shadow industry in the field came to an end.”

According to Prof. Birenbaum-Carmeli, foreigners also found their way to sperm banks. At the Emek Medical Center in Afula, for example, stored donations from non-Jewish men, which were mainly used by Haredi women.

And what about German donors, such as the Nazi officer?

“It is not unlikely that there were such cases, and it is doubtful anyone asked what their parents had done during the war.”

Questions that never go away

Sdomi's writing, like Birenbaum-Carmeli's research, connects silenced history with contemporary moral questions: What is the fate of this "new blood" that carries within it both the memory of the victim and the blood of the perpetrator? Is atonement for the sins of the father even possible, or is it merely the perpetuation of atrocities?

I admit, I too was haunted by countless existential questions throughout the interviews. What is clear is that while the blood may change, the questions remain unresolved: Can the sins of the father ever truly be atoned for, or do they become a new, indelible sin? What about the right to choose, denied to parents who never knew the origin of the sperm? And how does one live with the possibility that Nazi-Jewish children walk among us?

Every new revelation will raise equally heavy questions: What do we do with this information, with the meaning of roots intertwined with both victim and perpetrator? Even today, 84 years later, the mirror Sdomi holds up to Israeli society remains crooked - and perhaps it is precisely for that reason that it continues to shake us, again and again.